Scientists have found evidence of colon cancer in an 18th-century mummy, which suggests that humans were genetically predisposed to the disease even before the advent of modern factors that are thought to be its cause.

In 1995, more than 265 mummies were excavated from sealed crypts in the Dominican church in Hungary.

These crypts were used continuously from 1731 to 1838 for the burial of middle-class families and clerics and provided ideal conditions for the natural mummification of corpses - low temperatures, constant ventilation and low humidity.

Some 70 per cent of the bodies found had been completely or partially mummified.

The preservation of the tissue samples and abundant archival information about the individuals buried in the crypts attracted researchers from around the world, all of whom where interested in conducting their own morphological and genetic studies of the human remains.

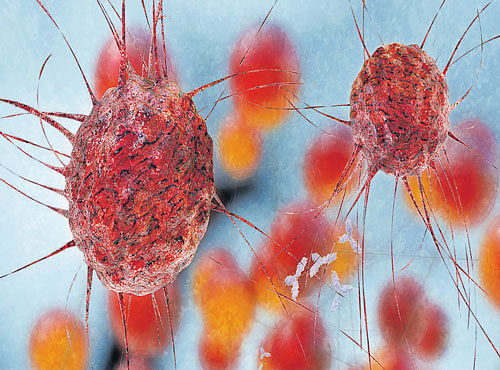

The modern plagues of obesity, physical inactivity and processed food have been definitively established as modern causes of colon cancer.

Researchers have also associated a mutation of the Adenomatous polyposis coli (APC) gene with the deadly disease.

"Colorectal cancer is among the most common health hazards of modern times and it has a proven genetic background," said Rina Rosin-Arbesfeld, from the Tel Aviv University (TAU) in Israel.

"We wanted to discover whether people in the past carried the APC mutation - how common it was, and whether it was the same mutation known to us today," Rosin-Arbesfeld said.

The researchers used genetic sequencing to identify mutations in APC genes that were isolated from the mummies.

"Mummified soft tissue opens up a new area of investigation," said Israel Hershkovitz, from TAU.

"Very few diseases attack the skeleton, but soft tissue carries evidence of disease.

It presents an ideal opportunity to carry out a detailed genetic analysis and test for a wide variety of pathogens," Hershkovitz said.

"Our data reveal that one of the mummies may have had a cancer mutation. This means that a genetic predisposition to cancer may have already existed in the pre-modern era," said Ella H Sklan from TAU.

The study was published in the journal PLOS ONE.