But how many have gone a little deeper, a little off piste, and seen the hinterland of the old Lycian kingdom, which sits quietly between the tourist meccas of Dalaman, Kas and Antalya on the southeast coast.

Where the regal cedar-clad mountains seem to fall into the sea as it changes from the cool emerald green of the Aegean into the deep cobalt of the Mediterranean — a corner occupied by settlers originally from Crete around the time of King Minos — a strand of the last maternalistic culture on earth, its fortress exterior a craggy coast and its sheer interior mountains almost impenetrable.

Hidden on this coast you will find the real Olympus, or ‘Olympos’ as the millennia-old ruined port is known, hidden in a deep ravine and sacked by pirates centuries ago. Here lies the real home of the sacred fire of the Olympics, the Greeks claimed as their own, which erupts from small fissures in the mountain as a self-igniting natural gas near the coastal village of Cirali.

This has been a continually burning natural flame for millennia, the origin of the legend of Belerephon and his flying horse Pegasus, who defeated the fire breathing Chimera and pushed it back into the mountain. The Chimera, called Yanartas in modern Turkish, is still there, breathing fire and unable to escape.

Perhaps venture further to the ancient city of Phaselis, the great port and city where Alexander the Great stopped en route to the Indus with his Macedonian army after defeating the Persians occupiers, or search for the huge caves where his army supposedly camped en route.

Travelling inland finds an unexplored and tranquil rural beauty, which unfolds into alpine green forests of cedar and pine as the ascent into the Akdagi and Beydagi mountains continues. The centre of this ancient land of Lycia is under threat of earthquakes such as those which devastated much of the Lycian civilisation and destroyed its cities in 141 and 240 AD.

The way is broken with small towns of old Ottoman wooden houses, houses that have vanished in so much of Turkey now, ancient olive groves and wandering goats. Looking back, the coast is still visible as the road climbs higher into the scrubby rocks and the azure sky, until at last the small dirt track to the side of the road indicates the way to Arykanda, one of the Aegean’s best kept secrets and one of the most beautiful sites of antiquity ever conceived by man.

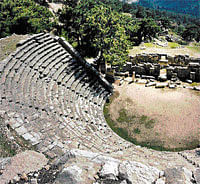

Arykanda is known to be over 4,000 years old and to be a rival to Delphi in Greece in ancient times because of its temple of Apollo, coupled with its unparalleled surrounding — the coast just visible from the edge of the huge stadium or from the largest amphitheatre.

It opens itself up to the visitor slowly, and without grand announcement, a precipitous gravel track cuts through a stony village, which seems to lead nowhere, until the entrance to the city comes into view. No metalled road guides the heavily laden tour buses to this jewel of antiquity, its wonders, charm and beauty, a hidden secret of the past.

Against the backdrop of a sheer mountain cliff thousands of feet high, the city is still being excavated and revealing perfect, untouched masterpieces such as mosaic flooring from Roman villas buried for 1,500 years, early Byzantine churches and enormous temples of Greek Gods.

Damaged by the earlier earthquakes and then abandoned totally at the end of the first millennium due to the drying up of its water source, so much of this metropolis still lies buried and unseen. The excavation of this unique and ethereal city has been the life’s work of Professor Bayburtluoglu from Ankara University, who now resides, most of the time, in the nearby village and has spent four decades with his team sifting and excavating the rocky soil to slowly reveal the glory of this astonishing city.

Travelling further into the mountains from here and entering the edge of the plateau, the vista changes — huge lakes and salt marsh with flat, fertile land laid out like a pancake between the snow-capped mountains surrounding the plain.

The road snakes through towns of small farms and old wooden houses, the women in headscarves and baggy-flowered salwar trousers, the men with tight-fitting skull caps, the yards in front of the houses scattered with carpets of red chillies drying in the sun, cobs of corn tied to the wooden balconies, swirls of pumpkin vines drifting across the tin roofs, neatly stacked woodpiles — it reminds me of highland Kashmir in the 70s, a rural simplicity and tranquil haven of clean air, with warm, welcoming people and a simple but hard life.

Leaving this hidden world in the south of Turkey takes the visitor via a twisting, winding and ever climbing narrow road to the highest pass in these mountains. Snow bound in winter, the Gulubeli pass is around 2,000 metres above sea level. The northern side of the pass stretches the immensity of the Turkish landscape, seemingly disappearing into infinity. There I know lie more Turkish wonders of the past.