I wake up to the song of a Whistling Thrush and the faint light of dawn filtering in through the large picture window. In minutes, I am ready to step out, warmly dressed, camera in pocket, and a hot cup of tea in hand. The October air is crisp and clear and carries the faint scent of pine. Jungle crows have joined in with their hoarse cawing. In front of my cottage, a paved stone path meanders its way down and disappears behind the trees. On one side of the path, the hill is terraced with fruit trees. The other side borders a pine forest.

Warmed up by the hot cup of tea, I walk towards the orchard, now teeming with activity. Hooded shrikes, natty tits, imperious bulbuls, elegant sparrows, tiny frenetic munias, white eyes and flycatchers flit about. Climbing up above the cottage and looking north, I see the faint outline of imposing mountains rising far above the many rows of tree-covered ranges. As the sun rises, Nanda Kot and the main peak of Nanda Devi take on a mellow golden hue.

When the bird activity subsides later in the morning, it is time to soak in the warmth of the sun in the small patch of green outside my cottage and delve into a book.

My cottage is located on a ridge overlooking the main city of Almora, Uttarakhand, well removed from its crowd and traffic. I have not come here with sightseeing in mind, but to escape the terrible air and noise pollution that is usual at this time of the year in the metro I live. To get to the nearest road, I have to walk through a stretch of pine forest, a stiff climb that invariably leaves me breathless. Pag dandis (footpaths) lead through the forest to the famous Chitai Temple, to the stream flowing at the bottom of the valley and to interior villages not connected by road.

Stream with no name

A couple of days into my stay here, I decide to walk down to the stream. The paved path, winding downwards, gives way to an uneven trail leading through patches of forest and a tiny village. Haystacks encircle the trunks of pine trees near the village, the base of the stacks lifted high up and off the ground. Comical, though, the sight is, it is also a reminder of the harsh winter to follow when fodder will be hard to come by. I see some movement on the trunk of a pine tree. A little bird with a long curved beak, its skin the colour and texture of the bark, is creeping rapidly up the tree in mouse-like fashion. This Himalayan bird has an appropriate name, bar-tailed tree creeper.

As I approach the bottom of the valley, I encounter a woman with a sickle sitting by the path. She asks me where I am going and starts to unburden herself. Three months ago she bought a cow and yesterday was the first day that she let it out to graze by itself. The cow did not return home and she has been searching for it since early that morning.

Wiping tears from her eyes, she says she will be content even if she comes across its carcass, but finds it hard to accept that the cow has simply disappeared. I wonder aloud if someone could have stolen it and she dismisses my thought. I am at a loss not knowing how to comfort her. As we part, the woman — from Bhuluda village, she tells me — expresses gratitude that I have even cared to listen to her story, and requests me to spread the word about her lost cow to people I meet on the way.

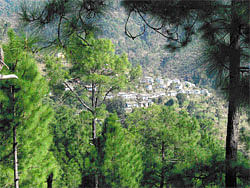

At the bottom of the valley stands a little Shiva temple, painted a bright pink, between two mountain streams that merge. Behind the temple, perched on a hill, is the village of Balta. From a distance, Balta looks neat and orderly with houses located in rows at different levels. The two-storied houses have tiled sloping roofs, and doors and windows painted in shades of blue and green. A narrow pedestrian bridge crosses the stream into the village of Vimtola.

There is no chai shop here and a villager grazing his cows and goats graciously offers to make tea at his home. There are leopards in the forests around here, he tells me. The missing cow may have been killed by a leopard, but certainly could not have been stolen. The stream has no name, it is just called a stream. The way back to my cottage is one long uphill grind for an hour-and-a-half. The children of Vimtola walk this route every day to reach their high school in Almora.

Of folklore

On another day, I spend the morning walking the trails in the Binsar Bird Sanctuary, an hour’s drive from my cottage. From the gap between trees, I spot Nanda Devi, with its unmistakable twin peaks, ethereal, floating above the clouds. The southern wall of high peaks and ridges ringing the main Nanda Devi peak — forming the almost impenetrable Nanda Devi inner sanctuary — is clearly discernable.

I wander into the forest rest house complex and the caretaker offers me some tea brewed from fresh oregano leaves and water from a nearby mountain spring. He tells me that there is no water shortage in Binsar because of the banj (oak) forest. When we talk about chir (pine) forests, he explains that chirs suck the earth dry. I am mentally transported to an evening I spent a couple of days back with a renowned archaeologist and scientist in Almora. Over tea, he tells me a folklore related to Nanda Devi.

Nanda is a goddess, but in folklore, she is also a simple village girl who pines for her mait (maternal home) just as every other girl. On her way to her mait, she rests under a chir and asks the tree how far it is to her home. The chir gives a rude reply and is cursed by Nanda — “No plants will grow under you, no animals will eat your leaves, no birds will build nests on your branches, and no bees will ever make their hives in them.”

When she stops under a banj tree, it welcomes her and asks her to treat its canopy as her own home. Nanda blesses the banj — “You will always remain green, birds and bees will make their homes on your branches, water springs will always be near your shade.”

A week passes in no time and I must return. But, I could stay on indefinitely here, in this charming place with its gentle people.