A few months ago, if someone asked you how many parents you have, you would have considered the question stupid. Not anymore. On April 6, 2016 a new chapter was opened in reproductive biology to help women carrying certain types of genetic mutations to have healthy babies. A study published in the September 2016 issue of New Scientist revealed that a Jordanian couple, who had been trying to start a family for nearly 20 years, was able to give birth to a baby boy using the DNA of three individuals.

Dr John Zhang of the New Hope Fertility Centre in New York, USA — to whom the couple had approached for help — discovered that the mother carries the genes for Leigh syndrome, a fatal disorder that affects the developing nervous system, and caused the deaths of their first two children. For the first time, Dr John tried, a new procedure called Mitochondrial Replacement Therapy (MRT). With the baby reported to be doing fine after its birth, MRT is being hailed as a milestone in fertility medicine. But what is it?

Inheriting mitochondrial DNA

We know that the DNA is stored in the nucleus of the cell. However, many of us may not be aware that our cells also contain mitochondria, which provides the energy required for cells to carry out their functions. The speciality of mitochondria is that they have their own DNA, known as the Mitochondrial DNA (mDNA). While we all inherit one set of chromosomes from both our parents, it is not the same case with mDNA. The offsprings always inherit the mDNA only from the mother.

So, if the mitochondrial DNA undergoes mutations and if this is present in the mother, all of her offsprings will inherit them. Mitochondrial DNA mutations are also associated with several inheritable diseases. Many of these diseases may strike early in life and tend to get worse with age.

Most mitochondrial diseases become apparent once the number of defective mitochondria in the organ reaches a certain level. Therefore, mothers with fewer defective mitochondria may not show any symptoms. In the case cited above, though the mother was free of symptoms, she still carried the mitochondrial mutations that cause Leigh syndrome.

So, how does one prevent inheritance of mitochondrial diseases? The obvious way is to prevent the inheritance of the defective mitochondria. But as the mitochondria are many, it would not be possible to select all the defective ones.

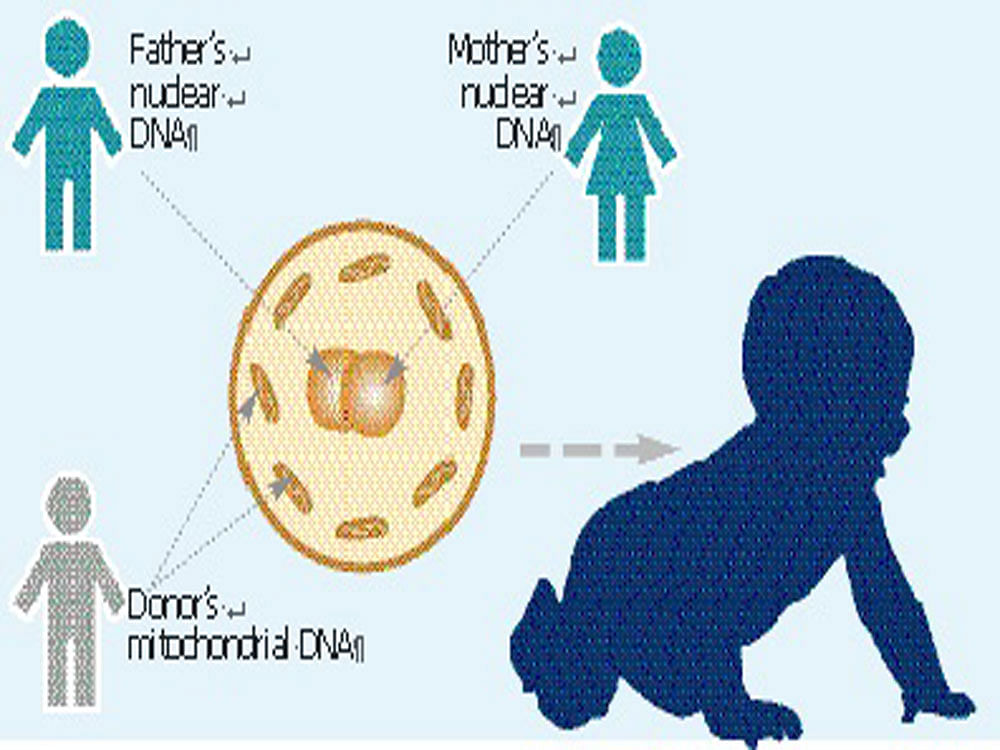

The next alternative is to replace mother’s entire mitochondria and provide the zygote (the fertilised egg) with a healthy set. The procedure essentially involves three people — the father, the mother and a healthy female mitochondrial donor. Eggs from the mother are harvested and the nucleus is carefully taken out using a microneedle under a microscope, leaving behind the mitochondria and all other organelles.

This egg is then fertilised with the father’s sperm using in-vitro fertilisation techniques. The fertilised egg is then allowed to develop into an early embryo in the laboratory. The team at New Hope Fertility Centre produced five such embryos and implanted one of them into the mother’s womb. Thus, when the baby was born, he inherited genetic material from three people.

Experts sceptical

As this procedure has been tried for the first time, it has raised a number of ethical and safety issues among fertility experts. It has no legal sanction in USA. Ethicists feel that mitochondrial transfer is a germ-line technology and a ethical boundary has been crossed. This may embolden others to manipulate germ cells to create what they call ‘designer babies’. Moreover, the question of compatibility between the mother’s nuclear genes and donor’s mitochondrial genes also arises. Though there is not much data on humans, experiments on mice have shown that such incompatibility may lead to obesity, metabolic disorders, accelerated ageing and other problems.

The procedure has other types of risks too. A large number of eggs will have to be harvested from both the mother and the donor to be able to select out an embryo for implantation. This is an invasive process and entails risk for the women

involved in the procedure. Furthermore, the extra embryos have to be discarded, which by itself is an ethical issue. Then there are psychological and societal concerns such as the identity of the person born through this procedure.

Another important question asked was will the procedure prevent the transmission of mitochondrial diseases? Some argue that it may not be possible to make nuclear transfer completely free from the mother’s mitochondria. When Dr John and his colleagues tested the baby’s mitochondria, they found less than one percent of them had come from the mother. Since it takes at least 18% of the mitochondria to be affected for the symptoms to show up, they hope the boy will be disease-free.