After a short seller in New York accused Gautam Adani of widespread fraud across his infrastructure empire, the Indian billionaire has spent much of this year assuaging foreign investors.

Now, Adani must also prove how he remains irreplaceable to PM Narendra Modi’s development agenda by pulling off a very different task: resettling a million Indians who populate Dharavi, the famed Mumbai slum, and turning the land into some of the world’s most expensive urban real estate.

Though Adani’s plans for Dharavi are still opaque after winning a bid to redevelop the area late last year, he will likely transform the slum into modern apartments, offices and malls. If successful, Adani would gain a major foothold in India’s financial capital, where he already runs one of the country’s busiest airports. The Dharavi revamp — one of the world’s largest urban renewal projects — could offer a blueprint for how to spur investment into sprawling informal settlements.

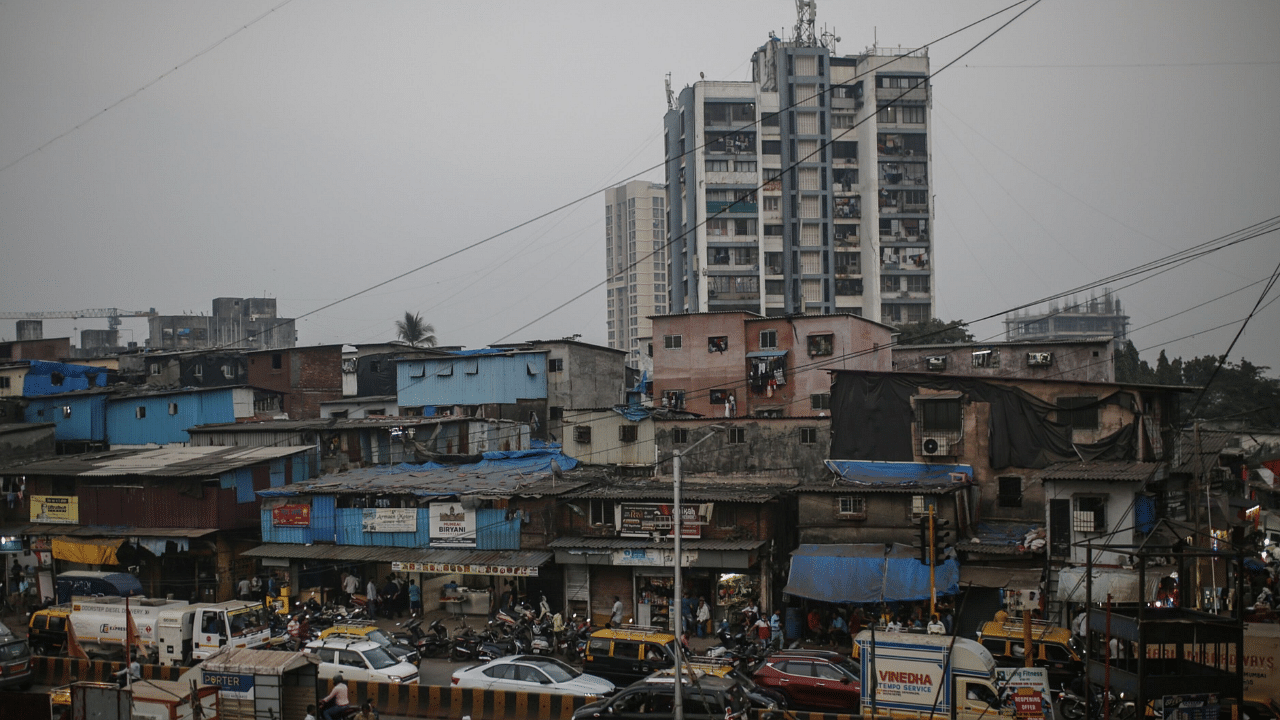

But the project is a tricky one for Adani, who’s been entrusted by Modi to fast-track India’s development. Dharavi, which is around the size of Monaco, is one of the biggest slums on the planet — and a key backdrop for the popular film Slumdog Millionaire. Mumbai’s administrators have struggled for decades to modernize the neighborhood. Dharavi’s revitalization requires pulling off three things virtually at once: acquiring large tracts of land, attracting investors to places without stable utilities and resettling massive communities.

In Dharavi’s tangle of rickety tenement buildings, many spoke of displacement, the collapse of their businesses and gentrification in a city already straining to accommodate 20 million people.

“We have no idea how Adani will redevelop Dharavi,” said Rajkumar Khandare, 43, whose leather business contributes to the slum’s $1 billion informal economy.

Adani’s ability to fund the estimated $3 billion project has also been questioned. The Hindenburg allegations erased more than $100 billion of market value from his companies, knocking the tycoon from his perch as Asia’s richest person. Though the Adani Group has vigorously denied wrongdoing, political parties have called for the revamp to be canceled.

An Adani Group spokesperson declined to comment until the government issues a final letter of approval for the Dharavi project.

Even with those hurdles, Adani’s ambition for Dharavi has cushioning, including strong political backing and the goodwill of more than two decades of friendship with Modi. With national elections scheduled for next year, Modi wants to show progress across long-delayed infrastructure projects in Mumbai — including finishing a metro network, a new coastal road and Dharavi’s redevelopment.

Adani has “tied his fortunes completely to the Modi government,” said Pramit Pal Chaudhuri, the South Asia practice head at political risk consultancy Eurasia Group. “They’re not going to give that up,” he said of the Dharavi project. “That’s politically too important.”

Dharavi started as an informal settlement for Muslim leather tanners. Migrants from across India flocked to the area, turning it into a cosmopolitan melting pot. As Mumbai expanded, the slum was no longer on the fringes of the city, but close to its industrial and financial center.

The neighborhood gained global attention from the 2008 film Slumdog Millionaire, which is largely set in Dharavi, though critics said it unfairly depicts the area as a one-dimensional eyesore. Its residents are far from powerless in shaping the city’s politics. Dharavi forms a key voting constituency, and the slum supports a large collection of cottage industries, from waste recycling to leather, textiles and pottery manufacturing.

Since the 1990s, Mumbai’s government has tried — and failed — to overhaul Dharavi. That changed last year when a faction of the Shiv Sena, the party that governs Maharashtra, abruptly took control of the state. Allied with Modi’s Bharatiya Janata Party, the new administration hastened a fresh Dharavi tender. Adani Realty, the tycoon’s real estate arm, emerged victorious with a $620 million first installment bid in November.

“The BJP is very much in the front seat in this government,” said Chaudhuri. “All these projects are going through as fast as possible.”

On Adani’s prospects, some fund managers remain bullish. Rajiv Jain, one of the biggest names in emerging-market investing, bought almost $2 billion worth of Adani Group stock in March, pointing to assets including Mumbai’s airport as signs of a healthy business.

Dharavi is especially appealing because of its proximity to the Bandra Kurla Complex, a swanky financial district that just three decades ago was barren marsh land. The area is one of Mumbai’s top draws, and houses glitzy shopping malls, embassies and bank offices, including JP Morgan Chase & Co.

The land is expensive. BKC commands net premium office rents of $97 per square foot on an annual basis. That compares to $101 in London’s main financial district and $102 in downtown New York, according to real estate broker Jones Lang LaSalle Inc.

BKC’s planned layout contrasts with the chaos of Dharavi, which is separated from the complex by the Mithi river. From an office with panoramic views of that divide, S.V.R Srinivas reflected on the challenges of redeveloping Dharavi.

“We always thought Mumbai would be the next Shanghai, but unfortunately it remains only Slumbai,” said Srinivas, a top official at the Mumbai Metropolitan Region Development Authority, which is overseeing Dharavi’s revival.

Housing is one quagmire. In order to qualify for resettlement, Dharavi’s residents must prove that they’ve lived there prior to Jan. 1, 2000. But Srinivas said as much as 40% of the population don’t have records.

The government has so far secured less than 50 acres (20 hectares) of nearby land to build affordable housing for Dharavi’s residents in Mumbai, which sits on a tightly packed peninsula.

“We have to deal with them,” Srinivas said. “You cannot just say, ‘I’ll throw them out.’”

Once existing residents are relocated, Adani is free to develop the brownfield land into market-rated residential and commercial property. The conglomerate’s blueprint for Dharavi is not yet public, but Srinivas said the aim is to rehouse residents within seven years.

One optimist is Megha Gupta. Her online platform — called Dharavi Market — was set up in 2014 to expand the reach of the slum’s local artisans. On a recent afternoon, Gupta climbed into dilapidated structures to speak with business owners — and pointed out all that could be improved.

“I am very hopeful and optimistic that if these things happen, it’s going to work out,” she said.

Many in Dharavi are still concerned. Some worry that their homes and businesses will be relocated far from Mumbai’s center. Others are convinced that they’ll be shunted into tiny apartments with terrible amenities.

“There is nothing to rejoice about,” said Rajendra Korde, a local community leader and president of the Dharavi Rehabilitation Committee. “We don’t see the intent from the government or developer for a meaningful rehabilitation.”

Srinivas, the city administrator, said Adani will have to build hospitals, schools and new roads in Dharavi. But with Adani’s plans still vague, critics believe the neighborhood will ultimately become another BKC. Similar redevelopment schemes in India have often smashed the heart out of neighborhoods without meaningfully improving conditions for displaced residents.

Businessmen like Abu Bakar, who has crafted leather briefcases for more than a decade from a workshop in Dharavi, chose the neighborhood for its affordability. Now he fears being priced out.

“We might not be able to afford the rent,” said the 32-year-old, who heads a business his father started in 1980. “With our tiny margins, our profit will be much reduced.”

Even if Adani attracts investment, Bakar said it’s hard for people in Dharavi to see how the project will help small businesses that have sustained Mumbai’s economy for generations.

“With no hope for Dharavi, they are looking elsewhere,” he said.