By P R Sanjai and Bhuma Shrivastava

In June, Indian billionaire Mukesh Ambani and his aides ran into an unexpected dilemma when debating where to train the dealmaking lens of his empire next.

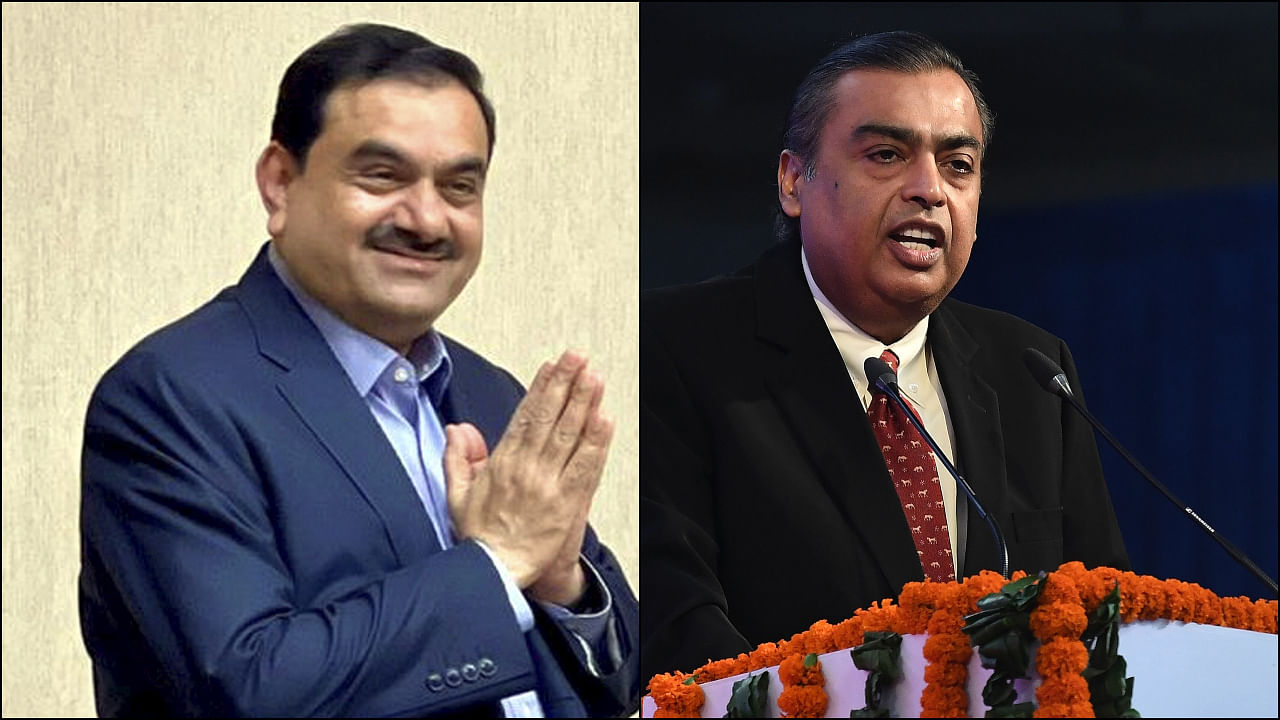

Ambani’s Reliance Industries Ltd. was contemplating buying a foreign telecommunications giant, when word reached them that Gautam Adani -- who had overtaken Ambani as Asia’s richest man a few months earlier -- was planning to bid in the first big sale of 5G airwaves in India, according to people familiar with the matter.

Ambani’s Reliance Jio Infocomm Ltd. is the top player in India’s mobile market, while the Adani Group doesn’t even have a license to offer wireless telecommunications services. But the very idea that he might be circling ground so core to Ambani’s ambitions put the tycoon’s camp on high alert, according to the people, who asked not to be named discussing information that isn’t public.

One set of aides advised Ambani to pursue the overseas target and diversify beyond the Indian market, while another counseled conserving funds to fend off any challenge on the home turf, according to people familiar with the discussions.

Ambani, worth $87 billion, ultimately never bid for the foreign firm, partly, the people said, because he decided it would be more astute to retain financial firepower in case of a challenge from Adani, who has seen his net worth surge more than anyone else in the world this year -- to $115 billion, based on data from the Bloomberg Billionaires Index.

After peacefully expanding in their respective domains for over two decades, Asia’s two richest men are increasingly treading the same ground, as Adani in particular sets his sights beyond his traditional areas of focus.

That’s setting the stage for a clash with widening implications both beyond India’s borders, as well as at home as the $3.2 trillion economy embraces the digital era, triggering a race for riches beyond the commodity-led sectors where Ambani and Adani made their first fortunes. The opportunities emerging -- from e-commerce, to data streaming and storage -- are reminiscent of the US’s 19th century economic boom, which fueled the rise of billionaire dynasties like the Carnegies, Vanderbilts and Rockefellers.

The two Indian families are similarly hungry for growth and that means they’re inevitably going to run into each other, said Arun Kejriwal, founder Mumbai investment advisory firm KRIS, who has been tracking the Indian market and the two billionaires for two decades.

“Ambanis and Adanis will cooperate, co-exist and compete,” he said. “And finally, the fittest will thrive.”

Representatives from Adani’s and Ambani’s companies declined to comment for this story.

In a public statement on July 9, the Adani Group said that it has no intention of entering the consumer mobile space currently dominated by Ambani, and will only use any airwaves purchased at the government auction to create “private network solutions,” and for enhancing cybersecurity at its airports and ports.

Despite such commentary, speculation is rife that he might eventually venture into offering wireless services for consumers.

“I don’t underestimate a calculated entry by Adani into the consumer mobile space later to compete with Reliance Jio, if not now,” said Sankaran Manikutty, a former professor at the Indian Institute of Management in Ahmedabad, who remains a visiting faculty member there and has worked extensively on family businesses, telecommunications and strategy in emerging economies.

For decades, Adani’s business were focused on sectors like ports, coal mining and shipping, areas that Ambani stayed clear of amid its own heavy investments in oil. But over the past year, that’s changed dramatically.

In March, the Adani Group was said to be exploring potential partnerships in Saudi Arabia, including the possibility of buying into its mammoth oil exporter, Aramco, Bloomberg News reported. A few months before that, Reliance -- which still gets a majority of its revenue from businesses related to crude oil -- scrapped a plan to sell a 20% stake in its energy unit to Aramco, gutting a transaction that was two years in the pipeline.

Also Read: After cement, Adani to foray into healthcare

The two billionaires also have significant overlap in green energy, with each pledging to invest more than $70 billion in a space that’s heavily tied to the priorities of Indian Prime Minister Narendra Modi’s government. Meanwhile, Adani has begun signaling deep ambitions in digital services, sports, retail, petrochemicals and media. Ambani’s Reliance either already dominates these sectors or has big plans for for them.

In telecommunications, if Adani does start to target consumers in a big way, history suggests that prices could plunge amid the early phase of competition but rise again if the two companies secure a duopoly, with India’s wireless space currently dominated by three private players. When Ambani made his initial foray into telecoms in 2016, he offered free calls and very cheap data, an audacious move that saw costs across the board drop for consumers, but they are increasing again as he’s cemented his control.

On the surface the two men appear quite different. Ambani, 65, inherited Reliance from his father, while Adani, 60, is a self-made businessman. But they also have some remarkable similarities. Largely media shy, both men have a history of being fiercely competitive, disrupting most sectors they set foot in and then dominating them. Both have excellent project execution skills, are extremely detail oriented and dogged in pursuing business goals with a track record of delivering on big projects, analysts and executives who have worked with them say.

Both hail from the western province of Gujarat, Modi’s home state. They have also both dovetailed their business strategies closely with the prime minister’s national priorities.

Not all Adani’s dealmaking overlaps with Reliance, and he’s raced ahead with outlays on M&A even as Ambani has stayed cautious on spending heavily overseas amid the uncertain global outlook. Adani Group acquired the Haifa port in Israel in July for $1.2 billion. In May, he bought Holcim’s Indian cement units for $10.5 billion.

For now, most of Adani’s new forays are so nascent that the full impact is hard to immediately gauge. Yet analysts are in agreement that the two men are likely to play a big role in reshaping the Indian business landscape, potentially leaving increasingly vast portions of the economy in the hands of two families.

That could have marked consequences in a nation that has only seen income disparity widen over the course of the pandemic.

While India’s current economic advance is similar to America’s so-called Gilded Age in the 19th century, the South Asian country now faces risks of rising inequality, said Indira Hirway, director of the Centre For Development Alternatives in Ahmedabad.

“Rapid diversification and overlaps between them can lead to duopoly if they work together, hurting the smaller firms in these sectors,” Hirway said. “If they start competing, it can impact the equilibrium of the business landscape as both conglomerates will be fighting for resources and raw materials.”