On a sultry September morning, Claudie Cortellini headed into the vineyards to survey the grapes that go into her family’s heady Côtes du Rhône wines. In recent years, she has fought to ensure a good harvest as the climate grows warmer. But these days, she is facing an even bigger foe: a giant Amazon sorting center slated for construction near her land.

The project, a concrete-and-steel behemoth that would span nine acres, promises to bring hundreds of jobs to the Gard, an agricultural region in the south of France. Tourists are drawn to the countryside to see a landmark of monumental beauty: the Pont du Gard, a 2,000-year-old Roman aqueduct that rises above the valley like a dusty jewel.

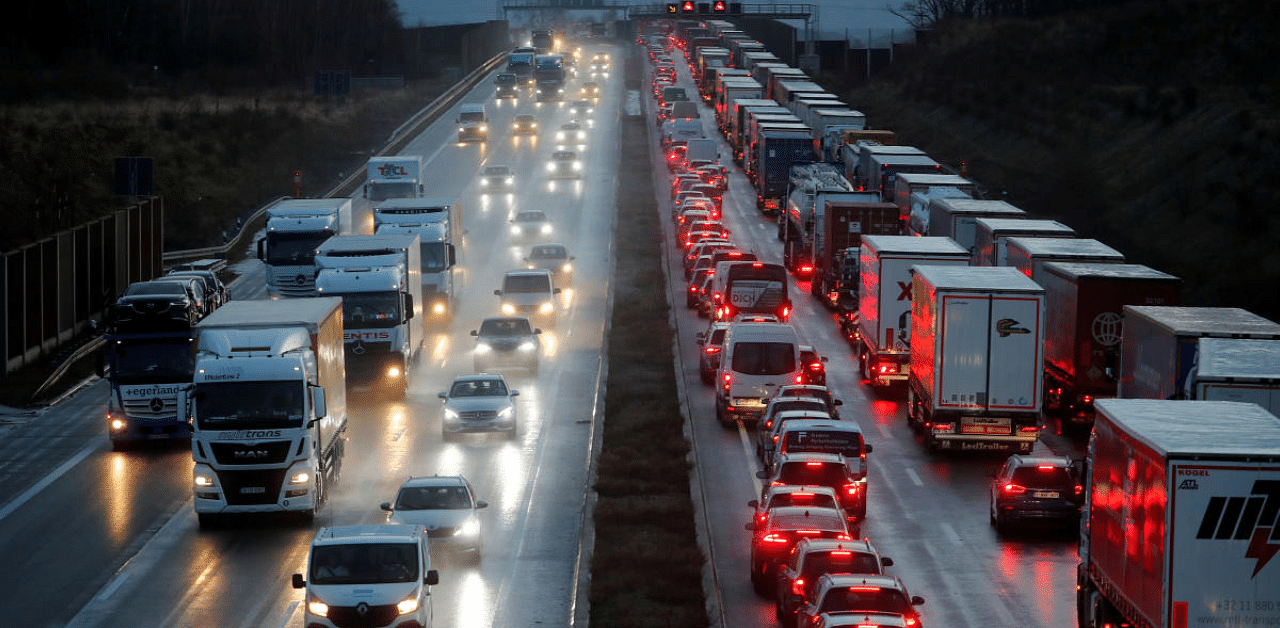

For Cortellini and worried residents, however, the jobs are not worth the pollution and explosion in traffic the Amazon warehouse would bring.

“They say they want to contribute to the economy,” said Cortellini, gesturing across her vineyard, Rouge Garance, toward the horizon where the warehouse would jut over 45 feet into the air. “But in the name of jobs, Amazon will do a lot of things that are damaging to the environment.”

The weedy plot carved out for Amazon — strategically near a six-lane highway — has become a point of contention in a bigger battle between rising environmental political forces and officials who say France can hardly afford to pass up opportunities for economic development, especially during a historically deep recession brought on by the coronavirus.

The Gard, despite picture-postcard beauty, has one of the nation’s highest unemployment rates. To people desperate for work, the environmental push to thwart Amazon — pointing to the stream of delivery trucks it will generate — seems out of touch with the hardscrabble reality facing families in the region. Many of them joined the Yellow Vest movement, which arose to protest income inequality after President Emmanuel Macron tried to raise taxes to fight climate change.

“We have people in distress — it’s our responsibility to find solutions and bring in economic activity,” said Thierry Boudinaud, the mayor of Fournès, a medieval-era village of 1,100 residents, where the sorting center would be built. “Big employers don’t often knock on our door. If Amazon doesn’t come, they will just go somewhere else.”

A spokesperson for Amazon declined to comment on the Fournès project, which is being spearheaded by a French warehouse developer, Argan. But Amazon widely promotes its environmental awareness and its pledge to reach net-zero carbon emissions by 2040, to the point of buying the naming rights to a hockey arena in its hometown, Seattle, and calling it Climate Pledge Arena.

Meanwhile, the American online giant wants to enlarge its footprint in France as it pursues international expansion. Since it arrived in 2000, Amazon has become a favorite in France, capturing nearly half of online spending in 2019.

It has deepened its grip worldwide as consumers in quarantine have stepped up internet shopping, reporting $88.9 billion in global sales in the second quarter, up 40% from a year earlier.

Amazon operates nine warehouses and sorting centers in France, at least five in poorer regions with high joblessness. They employ 9,300 full-time workers, and the company is reportedly looking to at least double the number of facilities. The sorting center near Fournès would be smaller than a massive pick-and-pack warehouse, according to the Argan proposal, but would sharply increase local traffic, with over 1,400 delivery vans and trucks rumbling in and out daily.

Jobs are a top priority in the Gard, which was devastated in the 1980s when the region’s coal mines closed. Though it has remade itself into a wine and tourist destination, unemployment is near 17%, more than double the national 7.1%. Last year, two factories outside Fournès shut down, leaving over 200 people without work. In nearby Nîmes and Avignon, joblessness in some neighborhoods tops 25%.

Needy residents of Fournès often solicit the town hall for work and occasionally seek help paying essential bills, Boudinaud said.

He and other local mayors would rather stoke growth by making their towns more of a destination for tourism around the Pont du Gard, a UNESCO World Heritage Site. But such projects take time. The Amazon facility would create jobs more quickly, and pay a development fee of 400,000 euros (about $470,300), as well as 180,000 euros a year in property tax, Boudinaud said. Fournès could use that money, he said, to upgrade a water treatment plant and the school cafeteria, which also provides food for low-income families.

As many as 240 full-time employees would sort Amazon packages in the highly automated plant, with more part-time workers hired around holidays. The location is close to farms and vineyards, and to a number of warehouses run by French companies — but none of them generate the heavy road use that is expected from Amazon.

The perceived ecological threat has galvanized environmentalists. Green party candidates captured elections this summer in major French cities, as voters pay more attention to climate change. Some want a moratorium on building any more Amazon-style warehouses in France.

“People in France understand what Amazon is,” said Patrick Fertil, a spokesman for ADERE, a local group trying to encourage jobs that work in harmony with the environment. “It’s monstrous warehouses that pollute. They play regions with high unemployment against one another and create low-paid jobs. And they destroy small businesses with cheap competition.”

Since Argan broke ground in November, over 27,000 people have signed an online petition against the project. Activists sued to halt construction, alleging that local officials would benefit from the sale of the property. Construction is now on hold until a court in Nîmes considers the case. Argan declined to comment.

Patrick Genay, a beekeeper with 300 hives in the area, is among those seeking to quash the Amazon project for good. The warehouse would destroy biodiversity that his bees need and risk polluting the Gard river with hydrocarbons, he said. Vehicle emissions from the motorway are already contributing to a decline in the bee population.

“We need plants and trees,” Genay said, standing amid a row of hives as clouds of bees buzzed around him. “We know the kind of world Jeff Bezos wants,” he added, referring to Amazon’s founder and chief executive. “But when you pave over everything, it’s an environmental disaster.”

In a statement, Amazon said that preserving the environment was “a core value,” and that it incorporated energy-efficiency technology into its latest fulfillment centers in France. The company cited an independent study showing online shopping curbed urban air pollution by reducing car trips to stores. After employees spoke out about Amazon’s role in climate change, Bezos pledged $10 billion in February to address the crisis.

“Contrary to conventional wisdom, e-commerce is inherently the most sustainable way to shop,” Amazon said.

For Cortellini and other activists, however, the presence of Amazon would create a huge nuisance in a region that has sought to preserve its character. Her quaint stone village, Saint-Hilaire-d’Ozilhan, continues an old tradition by taking children to school by horse and carriage. On the Pont du Gard, visible from Cortellini’s vineyards, activists from ATTAC, a militant environmental group, unfurled large banners this summer reading “Stop Amazon,” and “Ni Ici Ni Ailleurs” — Not Here or Anywhere.

Such arguments fail to resonate with people like Ali Meftah, who lives a half-hour away in a poor suburb of Nîmes, where unemployment is rampant. He and most of his young neighbors, many of them French Arabs, typically get access only to temporary, low-paid jobs. Those include picking grapes at harvest time in vineyards around the Gard.

“Yes, the environment is important — we’re worried about climate change, too,” Meftah said, gesturing around his low-income neighborhood of towering apartment blocks. “But our biggest concern is work. Amazon would mean more than 150 jobs. That’s 150 families who could put food on the table and create a stable life.”

Five minutes from Fournès, unemployment in the village of Remoulins is near 20%. Many stores on the main street are boarded up for lack of business after a nearby food packaging factory closed. Hassan Bergaiga, a grocery store owner, is eager for all the traffic from an Amazon warehouse, should it ever be built.

“It would be good for my business,” he said, standing against his storefront. “My little brother needs a job, too. If he could work in a place like that, he could move forward in his life.”

Fertil and other activists acknowledge the need for jobs — just not the type that Amazon would bring. “Instead of creating 150 jobs that will disappear with automation, why not create 50 small businesses with sustainable jobs?” he asked.

“The struggle against Amazon here is symbolic of a much bigger question: What kind of a society are we going to have?” Fertil continued, standing outside his cozy stone home.

“If it is one dominated by a monopoly that uses people, threatens the environment and only cares about consumerism,” he said, “that’s a world that we don’t want.”