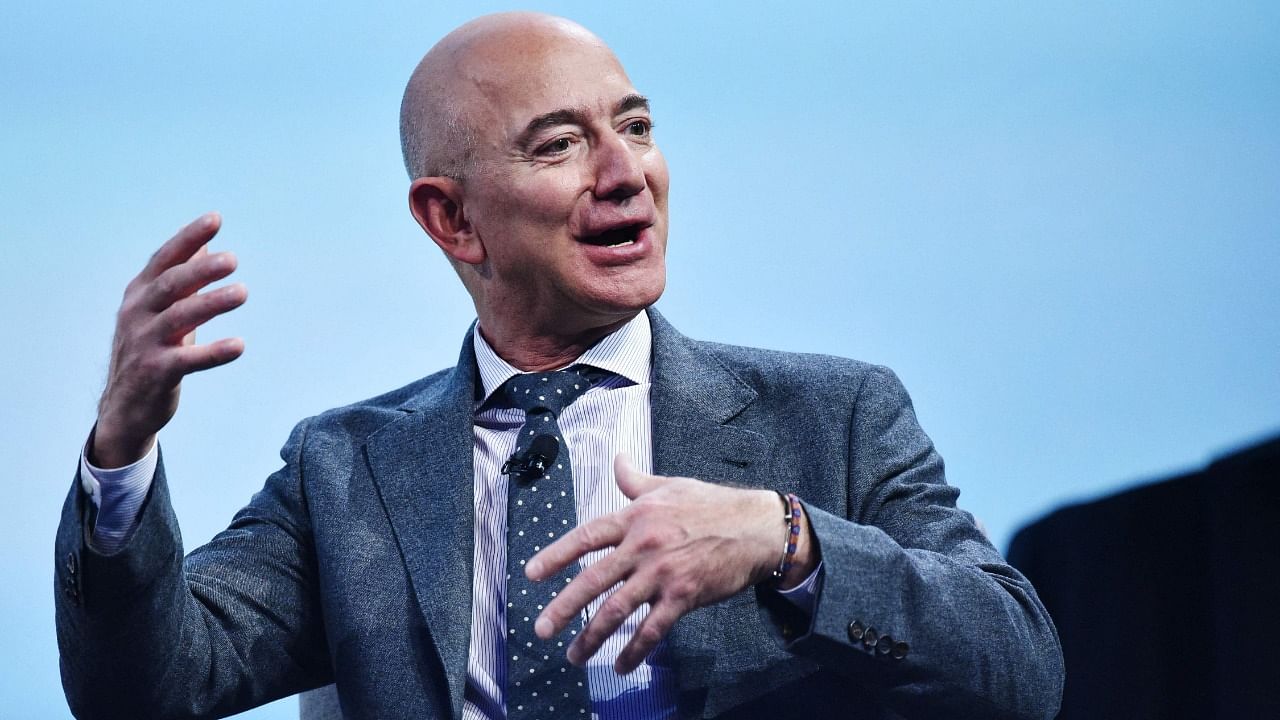

When Andy Jassy is elevated to CEO of Amazon Monday, taking the reins from its founder, Jeff Bezos, it will be one of the most closely watched executive handoffs in years.

But a much less heralded — though still deeply meaningful — change has already been underway at the company. Dozens of executives in Amazon’s upper ranks have departed in the past 18 months, many after working there for over a decade.

It is an unusual level of disruption inside the business. The departing executives don’t represent a huge slice of the top ranks, with hundreds of vice presidents now. But for years, Amazon’s leaders were considered lifers. Many had been there since the company’s earliest days. They were loyal to Amazon, whose rising stock price often made them wealthy.

Bezos epitomised that relationship. So did Jeff Wilke, who led the global consumer business, and Steve Kessel, who ran its physical stores, and others who introduced and ran key programs, including Alexa, free delivery and large parts of its cloud business. Now those leaders are gone.

Having Wilke and Bezos leave so close together amounts to “epic, tectonic shifts,” said David Glick, a former Amazon vice president who is now the chief technology officer at Flexe, a logistics startup.

Wilke and Kessel retired, but many vice presidents are leaving for top jobs at public companies or high-growth startups. Teresa Carlson, who over a decade built Amazon’s government cloud business, in April became the chief growth officer of Splunk, which provides data software, and Greg Hart, who once shadowed Bezos for a year and then launched Alexa and Echo, is now the chief product officer at the real estate firm Compass. Maria Renz, another former Bezos shadow who started at Amazon in 1999, is now a senior executive at SoFi, a personal finance company.

“Amazon has done a better job than anyone in the history of the world at staying Day 1 longer,” said Glick, referring to a phrase Bezos used regularly to encourage employees to act as if they were at a startup. “But you get to a point where you are so big, it can be hard to get things done. People want the fun of getting a little bit closer to the metal.”

He talks “every day,” he said, with Amazon leaders debating if they should make a jump.

“You have this set of people who got to VP and it’s like ‘OK, what do I do now?’” he said.

Amazon is facing a shift that earlier generations of tech companies experienced as they grew and their strong founders stepped aside, said David Yoffie, a professor at Harvard Business School who served on Intel’s board for 29 years. Amazon’s overall workforce has doubled in the past year, to more than 1.3 million.

“Intel, Microsoft, Oracle — you see this pattern,” he said.

Even before a founder leaves, executives sense a business is approaching a new era, he said.

“People get the idea that Jeff is going to be transitioning, and that leads people to start thinking about other options,” he said, adding that as companies get large, executives can often find less bureaucracy and more financial upside if they leave.

“We’ve had and continue to have remarkable retention and continuity of leadership at the company,” said Chris Oster, an Amazon spokesperson. The average tenure is 10 years for vice presidents and more than 17 for senior vice presidents, he added.

Bezos long played up the longevity of deputies. At a forum in 2017, an employee asked him about the lack of diversity on his senior team, known as the S-Team, which was almost exclusively white and male, and Bezos said it was a benefit that his top deputies had been by his side for years.

Any transition on the team, he said, would “happen very incrementally over a long period of time.”

In recent years, Bezos has stepped back from much of Amazon’s day-to-day business, focusing instead on strategic projects and outside ventures, like his space startup, Blue Origin, giving his deputies even more autonomy.

Bezos, 57, reengaged on day-to-day matters early in the pandemic. But in February, he announced that he planned to step down from running Amazon and would become executive chairman of the company’s board. On July 20, he is scheduled to fly aboard the first manned spaceflight of his rocket company.

Bezos’ handoff came not long after Wilke, long seen as a potential successor, announced his departure.

“So why leave?” Wilke wrote in an email to staff in August announcing his plan to retire. “It’s just time.” His last day was March 1.

Bezos anointed Jassy, 53, a long-serving deputy who built and ran the cloud computing division, to take over as CEO. Jassy has worked so closely with Bezos that he has been viewed as a “brain double,” helping conceive and spread many of the company’s mechanisms and internal culture.

Shifts at the top have trickled down. With Jassy’s ascent, Amazon Web Services needed a new CEO. It hired Adam Selipsky, who ran Tableau, a data visualization company that Salesforce acquired in 2019. Selipsky had worked at AWS until 2016, when the cloud business was a less than one-third the size it is now.

Dave Clark, who had run Amazon’s logistics and warehousing operations, was promoted to Wilke’s former role, running the company’s entire consumer business. He had already taken over responsibility for Amazon’s physical stores after Kessel, an S-team member who started at Amazon in 1999, retired early last year.

Many of the senior leaders it has brought in from the outside have run large, mature businesses.

Alicia Boler Davis, a former General Motors executive and a protégé of GM’s CEO, Mary Barra, joined Amazon in 2019 to run its vast fulfillment operations. Last year, she became the first Black member of the company’s senior leadership team. A former Boeing executive, David Carbon, now runs Amazon’s drone delivery team, and its video and studio business is led by Mike Hopkins, former chair of Sony Pictures Television.

Many other jobs are opening up, too. In April, the online business news site Insider tallied at least 45 vice presidents and other executives who had left Amazon since the start of 2020, and since then, at least a half-dozen more have departed.

Some have gone to leadership roles in public companies or well-funded startups, like American Airlines, Redfin, StitchFix and Stripe.

This week, Dorothy Li joined Convoy, a digital trucking network, after more than 20 years at Amazon. She said the pandemic had made her rethink her priorities. She saw how critical logistics were to serving people, and she was optimistic that making trucking more efficient could reduce emissions.

“There is a desire to go back to build, and the mission for Convoy really resonated with me,” she said.

As Convoy’s technology chief, she said, she viewed herself as a key part of the strategic leadership team. Three days into the new role, she said, “It’s exciting, exhilarating and a little nerve-racking, which is frankly part of what attracted me.”

Yoffie, the former Intel board member, said to expect even more shifts in the months ahead, as Jassy begins making changes as CEO.

“They want to put their stamp on it,” Yoffie said. “They always do.”