Facebook's pledge to tackle falsehoods about global warming came under scrutiny on Wednesday as a study found the social media giant failed to flag up half of the posts that promote climate change denial.

The report by the Center for Countering Digital Hate (CCDH), a London-based nonprofit, comes as Facebook's parent Meta has faced mounting criticism for its role in helping spread misinformation on the issue.

Here are some facts about climate change denial on social media and how it is tackled.

What does the report say?

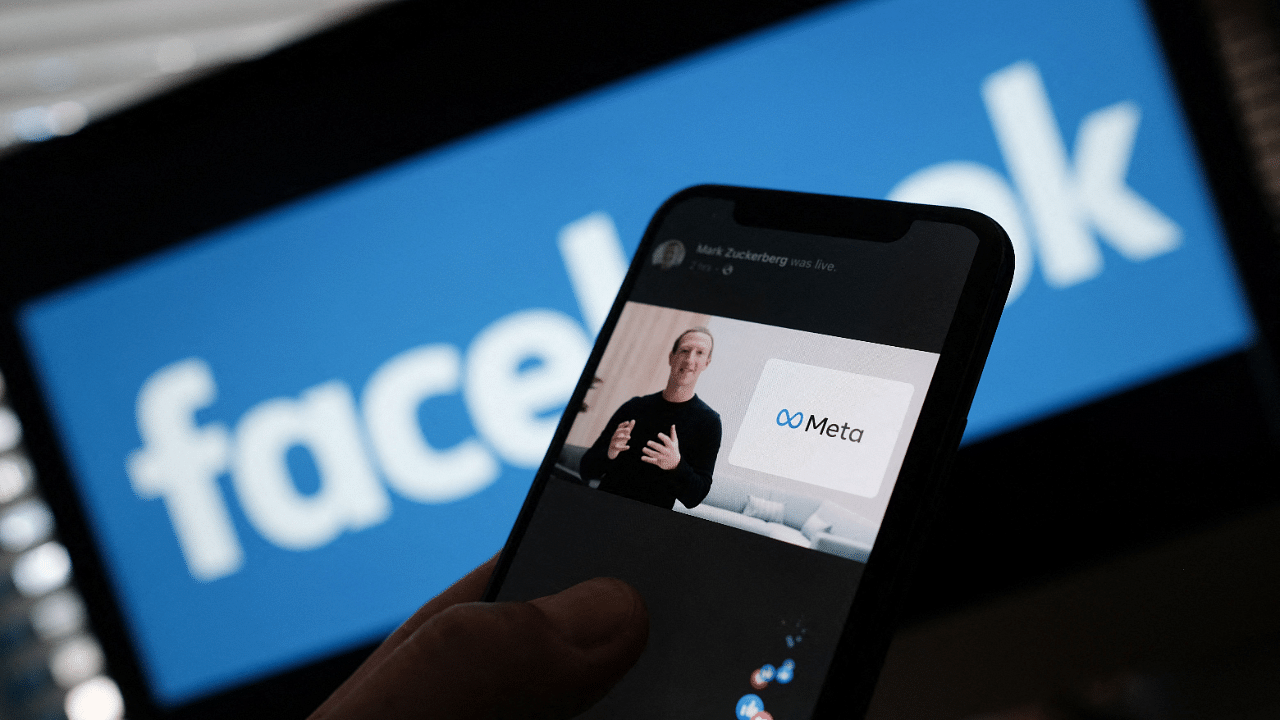

In February last year, Facebook, now known as Meta, said it would add labels to some posts about climate change to direct users to a new Climate Science Center, a hub set up to provide reliable information on the topic.

The CCDH said an analysis of 184 posts, published between May 2021 and January 2022 and pushing articles featuring climate denial content, revealed 50.5% did not have any labels.

The posts analysed were published by 10 news outlets that CCDH say are the most popular spreaders of climate falsehoods on the social media platform.

Meta said that during the timeframe of the report, it hadn't completely rolled out its labelling program, something it said "very likely impacted the results".

"We combat climate change misinformation by connecting people to reliable information in many languages from leading organizations through our Climate Science Center," the firm said in a statement, adding that it also worked with a global network of independent fact-checkers to review and rate content.

Also Read | Out with the Facebookers, in with the Metamates

Why does it matter?

Studies have suggested that in the United States, in particular, attitudes towards climate change are often driven by personal politics, with those on the right more predisposed to disbelieve that man-made emissions are warming the planet.

Researchers say that exposure to misinformation helps entrench such beliefs.

"People have a bias for the status quo. They don't want things to change," said Stephan Lewandowsky, a cognitive psychology professor at the University of Bristol in Britain.

"When people hear something scary about climate change ... many will be predisposed to dismiss it simply because it means a massive change and they're just afraid of that."

Moreover, misinformation creates confusion which can breed inaction at the very time when emissions urgently need cutting, said Kathie Treen, a University of Exeter researcher.

How are social media firms tackling the problem?

Social media giants have chosen different lines of attack.

Google has banned ads on content that contradicts scientific consensus on climate change on YouTube and its other services.

Facebook has launched its climate science information centre to elevate credible sources and added labels to climate change posts driving readers towards it.

Twitter has adopted a similar strategy, creating "hubs of credible, authoritative information", while Tik Tok says it removes misinformation and has introduced banners warning users about unsubstantiated content.

What do the critics say?

While the CCDH report points to patchy implementation, experts say the measures are anyway too meek, citing the much stronger tools deployed over Covid-19 and hate speech.

Facebook information labels, for example, only appear in some countries. They warn readers about misleading content with messages that suggest they go "see how the average temperature in your area is changing. Explore climate change info".

While there is some evidence that labels can reduce sharing of misinformation, there are concerns that many users could ignore or simply fail to notice them, said Treen, whose research focuses on climate misinformation online.

Facebook also generally does not remove misinformation in posts unless it determines they pose imminent real-world harm, as it did for falsehoods around COVID-19. It also exempts opinion articles and politicians from its fact-checking system. "By failing to do even the bare minimum to address the spread of climate denial information, Meta is exacerbating the climate crisis," CCDH's head Imran Ahmed said in a statement.

Are there any other options?

Social media firms have a wide set of tools available to tackle misinformation - but no silver bullet said Treen.

These include detecting malicious accounts then either restricting or banning them.

Algorithms can also be tweaked to give less prominence to misleading content - but given computers' limited understanding of context and nuance, this is prone to errors, she said.

Corrections can also be effective, but have to come from a reliable source and, in some cases, risk making some readers more fervently believe the original information, Treen added.

Labels can also be used more aggressively and put on top of misleading content rather than over or below, making it harder to access, said Lewandowsky.

Teaching people how to spot misinformation, encouraging them to stop and think about what they read and to critically evaluate it is also helpful - and can be done online, through games or prompts, said Treen.

But some of this needs to happen in the real world, added Lewandowsky. "We have to educate people at better discerning quality information. That starts in school," he said by phone.

Watch the latest DH Videos here: