India needs a minister for investment. Whoever wins the May 23 election count, the next government must find somebody who will boldly open the doors to American and Japanese capital.

Another statist intervention in a country that labours under an excess of bureaucracy might not look like much of a solution to anything. But for India to break free from the lower-middle-income trap* will require officials to marshal and allocate every scrap of funds prudently, and correct mistakes swiftly.

Just having a minister of finance isn’t enough, as India’s own experience has shown. From power and airlines to telecommunications and lending, large Indian businesses are failing at an alarming rate. But providers of capital — whether banks or capital-market investors — haven’t a clue about how to recover anything.

It’s time for a technocrat to step in to deal with stressed investments, with the finance minister’s portfolio truncated to broader macroeconomic and fiscal policy.

Financial services, including banking, insurance, pensions and capital markets, are currently a department within the ministry. Since September, the department’s website has featured nothing but personnel moves under its “What’s new” section, of the “director XYZ appointed to/removed from state-run institution ABC” type.

Turmoil in financial markets

Meanwhile, consider all the turmoil in India since September. The IL&FS Group, a vaunted infrastructure operator-financier, has gone bust with $12.8 billion in debt, casting a pall over wholesale funding markets. Jet Airways India Ltd., the country’s oldest private-sector carrier, has $1 billion in net borrowings and has stopped flying, while tycoon Anil Ambani has given up trying to repay $7 billion to creditors of his telecommunications firm by cutting deals outside of bankruptcy courts.

Now Ambani is beset by a new problem: a liquidity crunch and ratings downgrades at Reliance Capital Ltd., another of his main businesses. Reliance Home Finance Ltd., a unit, recently missed some debt payments. The trouble brewing in India’s shadow-banking world is the most scary of the country’s problems because it threatens to boomerang on both the ultimate users of funds (the construction industry, in particular) and their original providers (banks and mutual funds).

If nothing else, the new minister will have to intervene in the shadow-banking crisis to ensure half-completed buildings get finished and sold. India’s bankruptcy law is unable to do this. The outsiders trying to liquidate IL&FS at the state’s behest aren’t having much luck either. The government has to be in the driver’s seat, though not to write checks with taxpayers’ money.

A former central bank governor’s effort to push through a much-needed bankruptcy resolution process was abruptly curbed by the courts last month. A minister of investment could outline a novel solution, and the bureaucracy would have to find a law — among the dozens it oversees — to lend it legitimacy. Finding the missing legal space to act is the government’s job.

Foreign capital presents the most elegant solution for recapitalisation, but rather than asking investors for their money directly, a risky experiment is underway to take it indirectly. The monetary authority is nudging cash-strapped financial firms to borrow dollars oversees, bring them onshore and get them swapped cheaply for rupees by the central bank.

All it would take is for the new minister to say, “Why should we borrow investors’ dollars for three years when the likes of Warburg Pincus want to buy our stressed businesses instead? Why shield our businessmen from the consequences of their failures?”

Foreigners won’t stay forever. Once India Inc. recovers its footing, it will want to buy back assets it’s been forced to sell. Today’s local entrepreneurs may not want to pay the premiums that an American buyout firm or a Japanese insurer will eventually demand, but a new generation might. Some movement in India’s billionaires list wouldn’t be a bad thing.

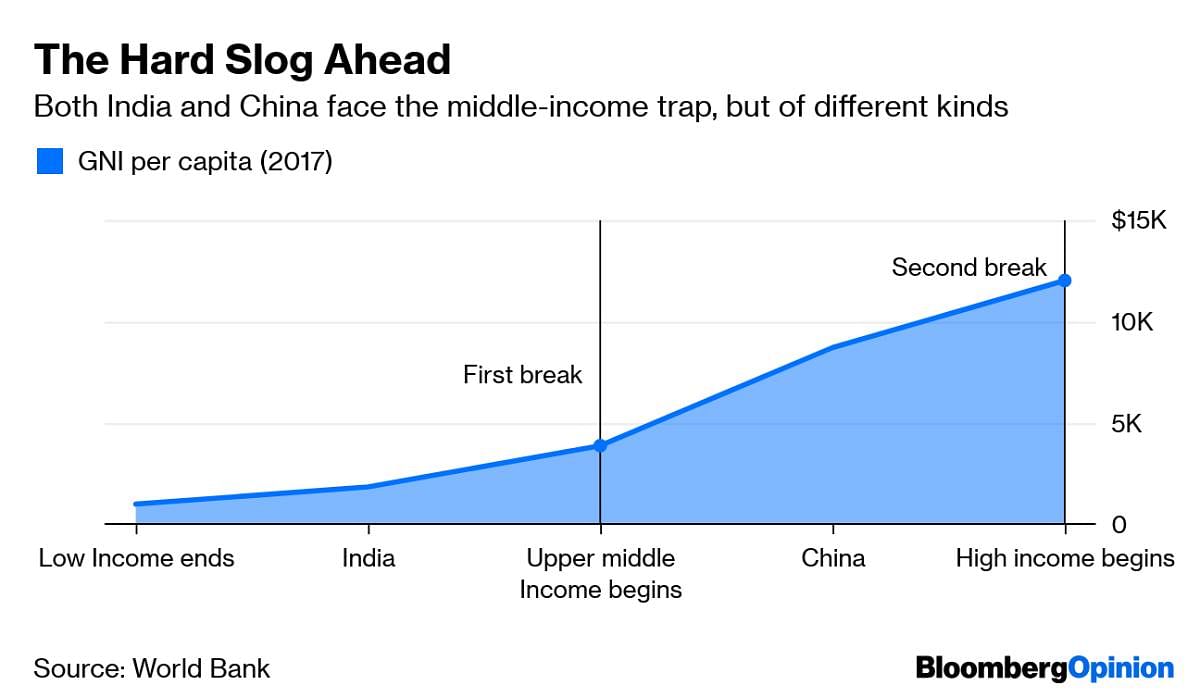

Beating the lower-middle-income trap was relatively easy for China because the People’s Republic, in the famous words of its reformist leader Deng Xiaoping, didn’t care if the policy cat was black or white. Beijing’s challenge is now the upper-middle-class barrier**. To cross it and become rich will require China to innovate and accumulate intellectual property. New Delhi’s priority, however, should still be to boost the health and education of its workers, and the efficiency of capital.

It’s a long game, but a minister of investment could at least get it going in the five-year window the next government will enjoy.

*An average Indian’s income of roughly $1,790 in 2017 places the country well below the halfway mark of the World Bank’s lower-middle-income range, defined as per capita gross national income of between $996 and and $3,895.

**China’s 2017 GNI per capita of $8,690 places it above the halfway mark of the range ($3,896-$12,055) defined as upper-middle-income.