Sharanya, a 12-year-old student, receives a link on WhatsApp from her friend, that asks people to click if they want to receive a government scholarship. The link takes her to a shady website which asks her to fill out her details, but does not have details about the scholarship. She gets suspicious and deletes the link. Later her mother tells her that this is a devious method to mine data and should never even be clicked on.

This is not an isolated incident. As a result of the sudden shift to online, social media became a part of students’ lives. Fake news and information present in social media made their way to academics. Not everyone is digital-literate enough to figure out the facts. This is where the need to impart fact-checking skills to teachers and inculcating critical thinking in children’s minds play a very significant role.

“If the received content is about politics or seems contentious, we have to certainly cross-check it. Sometimes the whole content won’t be fake but it would be put out of context, as happened recently in an article about cricketer Wriddhiman Saha, in which they picked the most explosive quote out of context as the headline,” points out Prithvi Prabhupani, a Class 12 student.

Ananya, a Class 11 student feels that the fact-checking of every piece of information that goes online is not happening. “It’s scary that anyone can write anything and share it on social media. People do believe in such fake news because they trust the person who sends it and that’s how the chain expands,” she notes.

Grooming them young

“As this shift was sudden, we made our children as well as parents aware of the perils of technology and how they can be safe online. We have been conducting workshops for children right from the nursery in order to inculcate a questioning mindset in them, especially while dealing with the information and content they get online,” says Sharon Lyngdoh, principal of Prakriya School, Bengaluru.

She highlights the need to encourage the questioning mindset among children, and how they should be encouraged by not judging or ridiculing their questions. “We conduct an annual four-day workshop for teachers, where we stay together and reflect on our behaviours, thinking patterns, group dynamics etc. When teachers come to understand themselves better, it translates to working with children, helping to inculcate critical thinking and other better mental models,” she adds.

Their school also collaboratively monitors most of the information that goes in WhatsApp groups of various classes. “Our parents' community is actively engaging, it helps the school to look at these things critically. The open community of school management, teachers and parents should actively work together to counter this spread of misinformation,” she says.

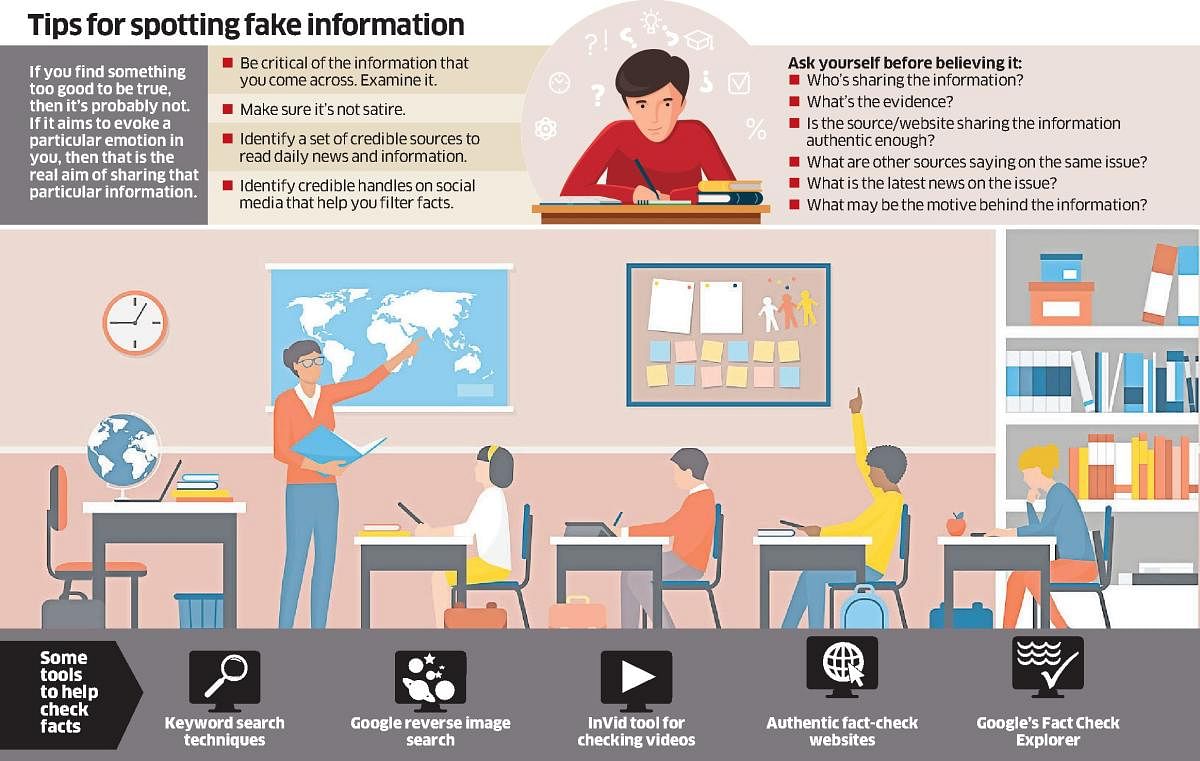

As the first line of defence, children, as well as teachers, should be taught particular fact-checking tools and techniques to counter fake news. There are several such training programmes being conducted by organisations such as ‘BBC Young Reporter’ which focus on the teachers and students from class 9 to 12. Kerala Government has also come up with a digital media literacy programme last year, in which around 6 lakh students across the state’s colleges and higher secondary schools are receiving continuous orientation. It covers five objectives: what is wrong information; why they are spreading fast; what precautions have to be adopted while using the content of social media; how those who spread fake news make a profit, and what steps can be initiated by citizens.

Satya Priya B N, a fact-check trainer from Hyderabad, who took part in the BBC programme, says, “In the programme, we talked about digital hygiene, how to be safe on the internet, and how to form a group to fight misinformation together. We taught some techniques and tools to identify and fight fake news. Imparting critical thinking, and how not to be biased in our own thinking was also part of the programme.” The programme received a good response.

Media literacy programmes

However, H R Venkatesh, Director, Training and Research at BoomLive stresses the need to include fact-checking in the school curriculum. "It is very important to have media and information literacy (MIL) in schools which teaches how to evaluate every bit of information that has been received. The need for MIL is much beyond just evaluating the news we are getting. Instead of just evaluating the news, the children should be able to dissect the coded messages in the information they receive on all communication platforms and should know how to keep themselves safe online,” he says, adding that his organisation is building such a comprehensive curriculum specifically for young children.

Venkatesh’s words resonate in an article written by Seth Ashley, who notes that the students can be good fact-checkers only if they have a broader understanding of how news and information are produced and consumed in the digital age. He writes that along with ‘fake news’, students should also be aware of what is happening to the ‘real news’, and how social media platforms have replaced them as news sources. He says that the social media algorithms provide the news that the consumers like and confine them in a ‘bubble’.

He also talks about the need to educate students about the way news is constructed, as most of the time news producers’ desperation to get ‘both sides' of a story can create a false equivalence, like on the issue of global warming where only one side is supported by actual evidence. If students are made to think of news as a public good like clean air or water, then it’s easy to see how we could all benefit from a news environment, he writes.

"There is no one-size-fits-all kind of approach to tackle such a rampant issue like this one, but we can talk about these things with children on a regular basis, and it should be a long and continuous process," observes Sharon Lyngdoh.