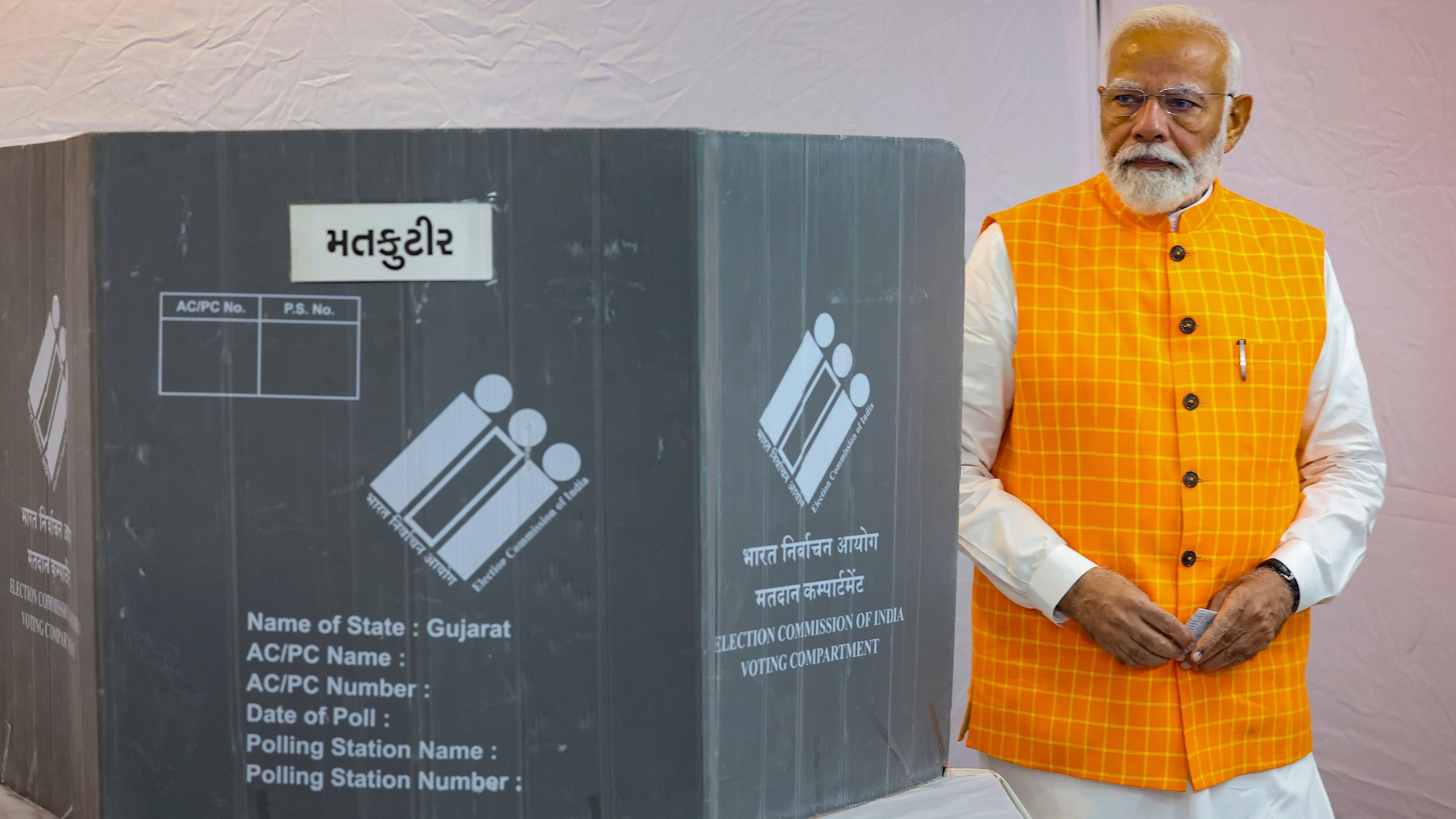

Prime Minister Narendra Modi casts his vote at a polling station during the third phase of Lok Sabha elections, in Ahmedabad, Tuesday, May 7, 2024.

Credit: PTI Photo

By Dan Strumpf and Sudhi Ranjan Sen

As India’s general election nears the halfway mark, falling voter turnout is prompting concerns about voter disengagement in the world’s largest poll.

Analysts and political party figures say there are good reasons for the decline and the lower participation doesn’t necessarily suggest an advantage for either side. Even so, the drop has raised questions about the ruling BJP's support, with uncertainty spreading to financial markets.

This week saw as many as 17.2 crore eligible Indians going to the polls in phase three of the country’s marathon seven-phase election, which runs through June 1. Turnout was 65.7 per cent, lower than in phases one and two and down from 67.4 per cent in the last general election in 2019, according to the Election Commission of India.

While it’s too early to offer a definitive explanation for the decline there are a handful of likely factors. Foremost among them: Voters are having a hard time getting excited about a contest that looks far from in doubt. Pre-election polls pointed to Prime Minister Narendra Modi cruising to a third five-year term in his contest against a diminished opposition.

Another possible factor: Modi’s BJP accomplished a number of its key second-term objectives, including the removal of autonomy for Jammu and Kashmir and the controversial construction of the Ram Mandir in Ayodhya. That’s left the party short on big new campaign promises to animate turnout this year.

“This time there is no big emotive issue on which the election is being contested, no new leadership on the campaign trail,” said Rahul Verma, a fellow at the Centre for Policy Research, a New Delhi think tank.

Investors said low turnout was weighing down Indian markets, with the country’s main stock index suffering its biggest one-day drop in four months on Thursday over concerns that low participation could hurt Modi’s re-election prospects.

There are other possible factors. A scorching heat wave has smothered much of the country in recent weeks, with temperatures as much as 5C above normal on polling day in many places, including the states of Tamil Nadu, Kerala and Sikkim.

Hanan Mollah, an eight-time lawmaker from one of India’s communist parties, points to lower voting in rural areas as well, which he says is due to migration from rural to urban areas in recent years. Migrant workers, fearing they’ll lose their jobs, are unwilling to return to their home villages to vote, he said.

The hangover from India’s Covid-19 fight may also be at work. Some analysts said Indians who died during the coronavirus pandemic may not have been removed from voter rolls. If true, that could be inflating the electoral body’s count of eligible voters and depressing turnout. A 2022 study by the World Health Organization estimated 47 lakh Covid-19 deaths in India, nearly 10 times the official government figure.

“Covid deaths in India are significantly underreported,” said RJD MP Manoh Jha.

Anti-incumbency risks

Yet the drop in turnout remains a modest one for now, and doesn’t appear likely to benefit one side or the other, according to analysts and research on prior elections. A 2018 study on Indian state elections found that rising turnout had no meaningful relationship to election outcomes.

“We have no historical or statistical evidence to suggest that turnout increase or decline is related to anti-incumbency,” Verma said.

To be sure, voter turnout isn’t down across the board. In Assam and West Bengal, turnout was 85.5 per cent and 77.5 per cent, respectively, in phase three.

A member of the RSS puts the lower turnout down to the fact that the ruling party has achieved many of its promises in its decade in power and voters aren’t motivated to come out in large numbers like before. Opposition voters also aren’t turning up because they see defeating the ruling party as unlikely, the person said, asking not to be identified in order to speak freely about internal discussions.

Favourable turnout

The State Bank of India said a better measure of India’s voting patterns than participation rates is the outright number of voters. By that measure, the first two phases of India’s election saw 870,000 more voters casting their ballots compared with the first two phases of 2019, wrote Soumya Kanti Ghosh, chief economic adviser at the bank.

“We believe this provides a truer picture of democracy through free exercise of franchise,” Ghosh wrote.

Still, experts often point to turnout as a barometer for the health of a democracy. India’s turnout tends to compare favorably with that of developed countries, with the 2019 figure in the mid-range of countries in the Organization for Economic Cooperation and Development, according to data from the International Institute for Democracy and Electoral Assistance.

The recent drop has spurred a renewed get-out-the-vote effort by Indian election officials. The Election Commission last week said it gave orders to state officials to come up with plans to boost turnout, saying it was “disappointed” with participation in places including “India’s high-tech city” — an apparent reference to slumping turnout in Bengaluru.