Indian films have seen a violent disruption of the status quo with the resounding success of south Indian films such as ‘KGF: Chapter 1 and 2’, ‘Pushpa: The Rise’ and ‘RRR’. Stamped with an unmistakable flavour of rebellion and machismo, these films have captured the imagination of the public. With appreciation for them on the one hand and pitiless obituaries for Bollywood on the other, it is easy to forget that ‘the angry man’ hails from Mumbai and has just turned 50!

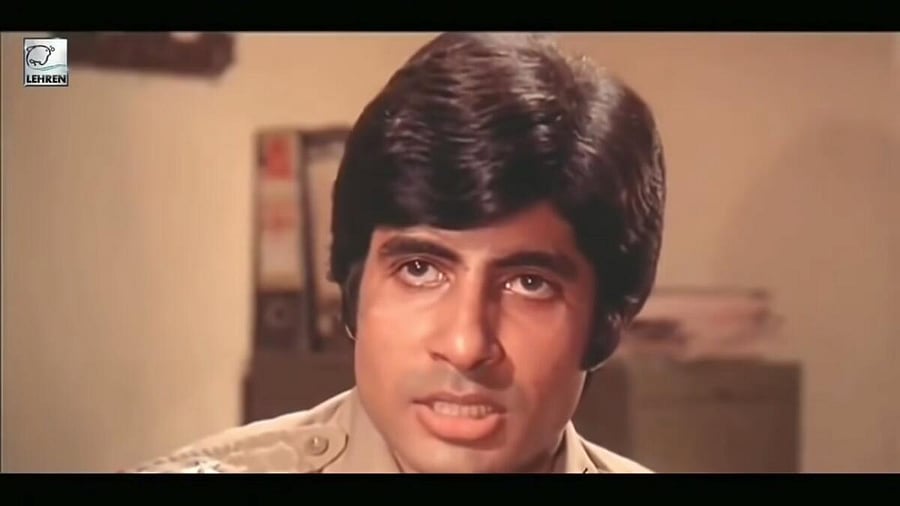

‘Zanjeer’, released on May 11, 1973, turned out to be a two-fold epoch. Firstly, it kickstarted Amitabh Bachchan’s till-then struggling career and initiated a long and eventful partnership with the firebrand writer duo Salim-Javed (Salim Khan and Javed Akthar), while also considerably adding to their clout as ‘kingmakers’. Secondly, it marked a paradigm shift in filmmaking. The movie’s essence was rooted in distrust of the system and a revolt over it. The portrayal of the protagonist (police officer Vijay Khanna) is sketched in shades of grey, from being the officer ready to take law into his hands to oscillate as the insecure man seeking to emotionally settle down in life. It shook the audience who were unaccustomed to an imperfect hero. In Akthar’s own words, “It broke all norms.”

What followed was ‘Deewar’ (1975), ‘Sholay’ (1975), ‘Amar Akbar Anthony’ (1977), ‘Don’ (1978), ‘Thrishul’ (1978), which expanded on the initial sketches seen in ‘Zanjeer’. Unsurprisingly, most of these were written by Salim-Javed. However, the genre slowly faded away when with time it lost the element of novelty and popular appeal.

Critics maintain that with disenchantment over the establishment in the mid 70s, when the society saw unprecedented unemployment, burgeoning corruption and a consequential rise in crime, the audience could easily relate to a hero who picks up the gauntlet and fights an inexorable battle. However, a candid Akthar says, “..It was not any formula, socio-political awareness or understanding of the contemporary aspirations that made us write this kind of a role. As a part of the society at the time, it appealed to us and we wrote it...”

Come present and we have travelled a full circle. While mainstream cinema went the way of sentimental family dramas in the 90s and early 2000s, problems following economic slow-down and Covid-19 related disruptions of life have brought back the angry young man. If one were to blame the current films for copying the plots from the 70s, the criticism must also extend to the latter, as they borrowed a great deal from ‘Mother India’ (1957) and ‘Gunga Jumna’ (1961). However, there exists a baggage of differences too. While one can see a clear boundary being drawn between right and wrong in the past, and forceful if not moral arguments justifying one’s entry into crime (the iconic clash between the brothers in ‘Deewar’, where Bachchan seeks justification for his crimes through the humiliations he bore due to his father’s deeds), of late we see a trend to glorify such characters without the necessary critical eye that they demand.

Thus we find Rocky in ‘KGF: Chapter 2’, totally unperturbed when informed that several men working for him are injured and merely says, “Hire new men, the work must not stop.” Even when confronted, the director fails to evince reasonable responses from the protagonist. Pushpa portrays the trauma endured by a fatherless child much better, although comes out as far too crass, making it hard to watch at times.

Another difference lies in the portrayal of supporting characters which completes the picture. It is impossible to imagine a ‘Zanjeer’ without Sher Khan, played flawlessly by Pran with characteristic elan and mannerisms of a Pathan. In fact, the iconic “Yaari hai imaan mera” scripted for Pran aptly sums up his character. While such a benevolence may no longer be as easily granted to a Pathan (unfortunately), no anchor role whatsoever in ‘KGF’ or ‘Pushpa’ comes out nearly as memorable. Thus, they end up one-man eulogies, much to the chagrin of the critic.

Anti-heroes are inevitable as all social superstructures face resistance from within which comes out as a clash of ideas. Such films are welcome as they make us question the system and the rot inside. However, bereft of criticality, the lines between white and black are completely blurred.