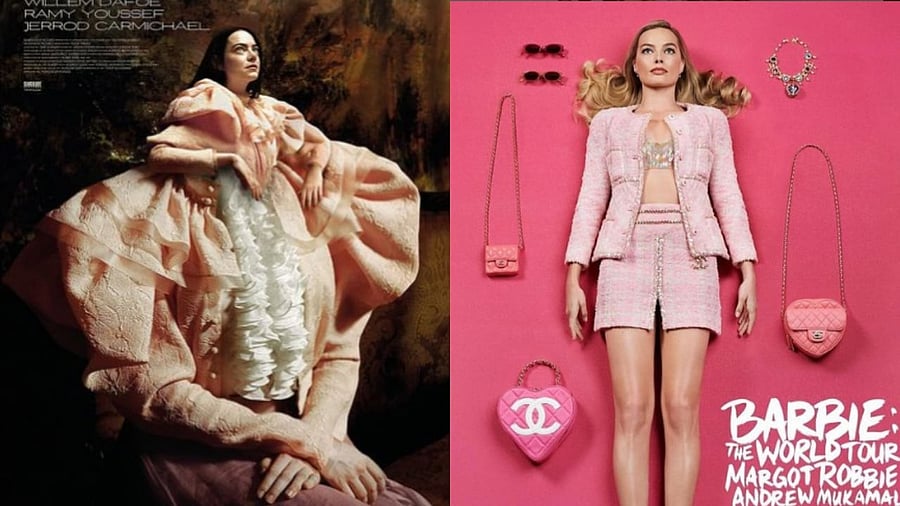

Posters of the films Poor Things (Left) and Barbie (Right)

Credit: Instagram/ @barbiestyle, @poorthings

One takes place in a bright, plastic world where everything is coated in pink. The other takes place in an isolated black-and-white world that transforms, “Wizard of Oz” style, into a flashy, steampunk domain.

Though they’re very different stylistically, the Oscar-nominated films Barbie and Poor Things are both modern feminist fables about the making of a woman. Both reframe the common stops on the coming-of-age story: The protagonists begin in a state of childlike innocence, then, each in her own way, pass through motherhood, ending in a place where they are both and neither mother and daughter, creating their autonomy from the place between these two states of womanhood.

Poor Things, from director Yorgos Lanthimos, takes its concept from Mary Shelley’s Frankenstein, in which a genius scientist jigsaws together and gives life to a monster who wreaks havoc while on an existential quest for knowledge. Here the 'Dr. Frankenstein' is 'Godwin Baxter' (Willem Dafoe), and his monstrous creation is 'Bella' (Emma Stone), a woman he has resurrected.

At first Bella babbles and stumbles around like a precocious toddler, learning to speak and move by imitating the adults around her. She then goes through a kind of adolescence beginning the moment she discovers sexual pleasure. Her sexual curiosity spurs larger curiosities about the world.

Through sex she discovers what she wants, and claims her agency to pursue it. She travels the world with a spineless cad, 'Duncan Wedderburn' (Mark Ruffalo), enjoying the rampant sex they have along the way. She’s fiercely independent the whole time, even though she has traveled far from the bleak, isolated black-and-white world of the Baxter home, where she was hidden away and always under supervision, into a colorful, wild world that appears as awe-inspiring and unfamiliar to her as it may to the audience, who find fresh new versions of cities like Lisbon and Paris.

It’s when Bella decides to work in a Paris brothel that she experiences the most freedom. She goes to lectures, political meetings and reads voraciously while earning her keep through sex. She’s no longer simply the naive daughter, seeing the world through Godwin’s warnings and advice. And she’s not the partner for Duncan, forced to tolerate his tantrums and fits in exchange for access to the larger world.

Though Bella gets two marriage proposals in the film, and even steps up to the altar for one, she never marries. She discovers she has already played the wife role in her former life; that’s when she was 'Victoria Blessington', wife and expectant mother, who jumped off a bridge because she didn’t want to give birth. Godwin’s experiment placed the brain of the unborn child into the skull of the dead mother, making Bella both mother and daughter.

This makes Bella a paradox of womanhood: Though Godwin performed the science, she is her own parent, her own creator. Because Bella embodies a woman who rejected her motherhood, rejected her future child, and yet is both, she is the summation of a sexual journey where she can be the mother without actually bearing all the social implications of motherhood.

Like Bella, the Mattel-made protagonist of Greta Gerwig’s 'Barbie' (played by Margot Robbie) appears to be a grown woman but has the sensibilities of a child. Her world is a giant playset come to life; everything is ruled by imagination, from the temperature of the water in the shower in her dream home to the pretend milk in a carton. She’s in an eternal state of play. She and the rest of the residents of Barbieland have no understanding of sexuality. They don’t even have genitals, as Barbie herself says.

Barbie’s evolution is more abstract than Bella’s; Barbie’s adolescence begins with her doubts, self-consciousness and thoughts of death. Her hero’s journey is a quest from her fantasy playland to the real world, where she hopes to find 'Sasha' (Ariana Greenblatt), the girl who used to play with her. Though Barbie locates her, she realizes Sasha is not the cause of her recent changes. Barbie is psychologically linked to the girl’s mother, 'Gloria' (America Ferrera), a Mattel employee whose thoughts of cellulite and death transferred to Barbie in Barbieland.

Barbie is the bridge between this mother and daughter, embodying the abandoned childhood of Sasha and the adult thoughts of Gloria. She’s set between two generations of women who at first feel disconnected in their politics, as when Sasha brutally cuts Barbie down as not the symbol of female empowerment she thinks she is, but an anti-feminist consumer product that damaged girls’ self-images. But Sasha, Gloria and Barbie reach a common ground in all the ways society oppresses, suppresses, silences and limits women.

A major step in Barbie’s awakening, and ultimately, transition into becoming not just a doll but a real woman in the real world, is her meeting with the ghost of 'Ruth Handler' (Rhea Perlman), the co-founder of Mattel and creator of Barbie. Handler tells Barbie she named her and 'Ken' after her children, and Barbie even adopts Handler’s last name when she travels back to the real world to stay.

Motherhood isn’t Barbie’s solution. But her discovery of a mother figure and her relationship with Gloria and Sasha also lead her to a place of newfound agency. In this sense, motherhood is less about literal children than about which notions of female autonomy are passed down through the generations, and which don’t make it.

In other words, these stories are also about a feminist lineage. Both Bella and Barbie are able to fully build and understand their identities when they get out from under the patriarchy and gain access to their inner daughter and inner mother. The point of both stories is that a woman’s freedom lies beyond the neat roles that society would exclusively prescribe her, whether that’s child, wife or mother. To be a free woman, like Bella or Barbie, is to be free of definition — or, rather, to be free to define oneself.