In Basu Chatterjee’s ‘Baton Baton Mein’ (1977), the hero’s father is almost always seen buried in his newspapers while his wife and son are arguing. Men poring over their dailies, oblivious to the domestic cacophony is a recurring image in Bollywood. Such scenes often appear in family dramas where a ‘saas’ is making her bahu’s life hell or family members are engaged in petty squabbles. The patriarch — shown with no or little influence on the matter — seeks refuge in the world of news. At times, earning a barb about his non-involvement, even. This scenario establishes their uninterestedness in the household drama and newspaper symbolises the perfect escape.

For the ubiquitous activity that it is, a newspaper is among the most handy props in film scenes. Characters scan through them over breakfast, a bystander waiting at a bus stop with a daily tucked under their arm, people discussing a news item at their neighbourhood adda — such vignettes blend in the fabric of the scene effortlessly. The continued depiction of newspapers on screen has incidentally become a showcase of the diversity of the Indian print media. Vintage periodicals, small local dailies, renowned names of Indian journalism — Hindi cinema seems to have captured them all.

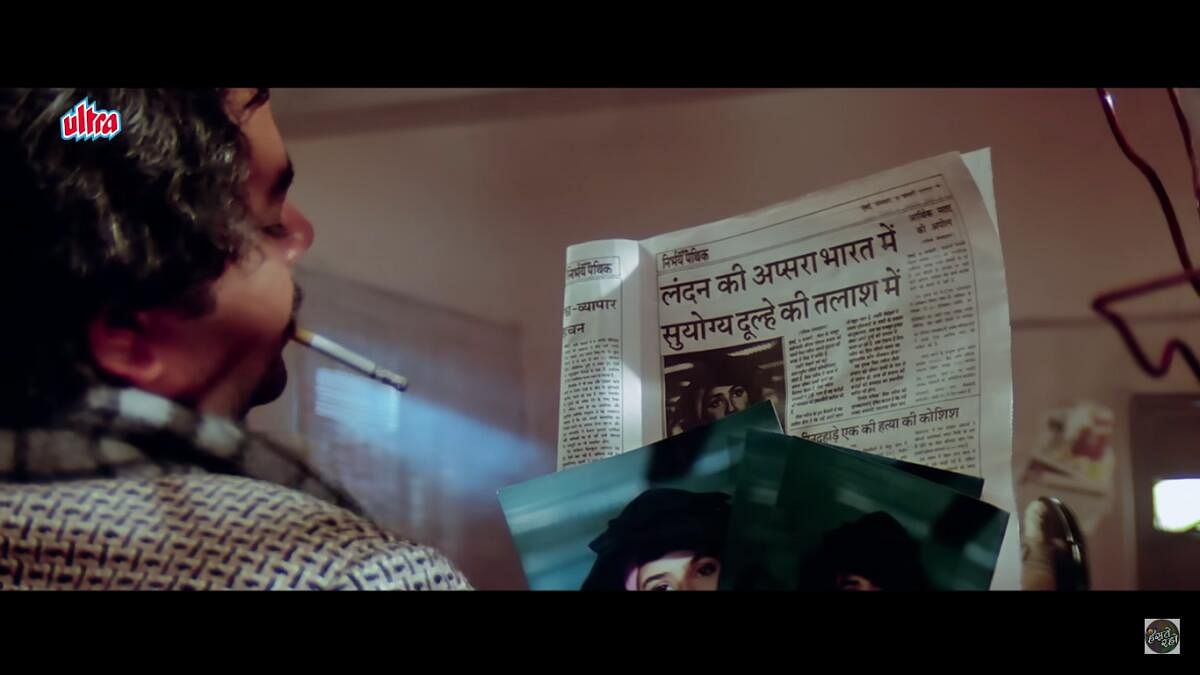

Sometimes a newspaper becomes more than a prop. It becomes a useful tool to relay information significant to the film’s plot. Like in ‘Andaz Apna Apna’ (1993), the newspapers announce the arrival of a rich NRI heiress and her intention to marry an Indian man. It is through these reports that the film’s heroes, Amar and Prem learn about her and hatch plans to marry her. Or in ‘Daag’ (1973), where the heroine discovers her husband’s death through a front page news report and makes an important life decision. The humorously titled The Crimes of India newspaper office in ‘Mr India’ (1987) bustles with activity and becomes an unlikely meet-cute spot for its lead pair: a crime reporter and a music teacher.

In black and white era films, one can catch glimpses of olden days dailies like Dainik Paigham, Khilafat Daily, Hindustan Standard and more. Some of them have now gone out of circulation. As have the iconic and more contemporary Mumbai brands like DF Karaka’s weekly, The Current and Behram Contractor’s The Afternoon Despatch and Courier. Both the papers appeared regularly in the films of the ‘70s and the ‘80s-‘90s respectively. On the other hand, The Statesman, Dainik Jagran, The Pioneer, Hindustan and other broadsheets — founded in pre-Independence India — are still around. One can actually track the design changes in their mastheads, fonts etc across films from different decades. It is also interesting to note that as the usage of the Urdu language dwindled in popular culture, so did the visibility of Urdu dailies in our films which until the ‘70s were a regular fare.

Bollywood films are also filled with sights of smaller, regional publications. Shadashiv Amrapurkar’s character in ‘Hum Saath Saath Hain’ (1999) reads what looks like a local journal called A to Z Politics. Mumbai-centric Hindi daily Hamara Mahanagar pops up in ‘Damini’ (1993). Since a lot of films are based and shot in and around Mumbai, it’s natural that Marathi papers would feature more commonly that any other regional language dailies. Tarun Bharat in ‘Naya Daur’ (1957), Lokmat in ‘Traffic Signal’ (2007), Loksatta in ‘Satya’ (1998), Nava Kal in ‘Raju Ban Gaya Gentleman’ (1992) are a few instances.

Speaking of Mumbai, the city’s two most prominent afternoon tabloids during the ‘70s-‘80s — Evening News of India and Free Press Bulletin — frequently featured in the films of that era. Hindi daily Dainik Vishwamitra was again a popular choice among Bollywood filmmakers whenever the scene demanded a news flash. The paper has a noticeable presence in ‘Jeevan Mrityu’ (1970), ‘Yakeen’ (’69), ‘Agent Vinod’ (’77), ‘Sawan Ko Aane Do’ (’79), and ‘Kaala Patthar’ (’79) among others.

Bollywood films don’t always resort to real newspapers. Some important films about journalism or where major characters are associated with the print media have had a great fictional newspaper in the mix. In ‘Bluff Master’ (1963), Shammi Kapoor takes up the job of a photojournalist for a tabloid curiously called the Bhookamp Weekly while Aamir Khan plays a canny reporter for the Daily Toofan in ‘Dil Hai Ki Manta Nahin’ (1991). Gulzar’s ‘Aandhi’ (1975) has two papers Zamana and Watan covering the updates of a bitterly fought election.

There are also films that have captured the inner workings of the press. In ‘Mashaal’ (1984), Dilip Kumar plays the editor of an independent newspaper Dainik Elaan that takes on the mighty and the corrupt. The film diligently depicts the everyday functions of the press and the tedious process of printing and publishing. Rakesh Sharma’s ‘New Delhi Times’ (1986) remains peerless for its portrayal of objective reporting and fact checking while ‘Main Azaad Hoon’ (1989) speaks about manufactured news and unscrupulous media practices.

Newspapers can also easily establish the cultural identity and habits of the characters in films. The Parsi characters in ‘Khatta Meetha’ (1978) read Gujarati newspapers Jam-e-Jamshed and Mumbai Samachar — much in line with the linguistic custom of the community. More recently, during the opening sequence of ‘Laal Singh Chaddha’ (2022), a man can be seen flipping through the pages of Punjab Kesari keeping with the milieu of Pathankot, Punjab where the film opens.

When applicable, the proper use of newspaper(s) adds to the authenticity of a period film’s setting. Nandita Das’ 2018 biopic ‘Manto’ has a scene where Saadat Hasan Manto is visiting his friend in Pakistan post partition. The writer notices a bystander reading one of his works in Daily Imroze — the neighbouring nation’s new and popular Urdu daily back then. It was supported by Manto’s contemporaries and literary greats like Faiz Ahmed Faiz. In fact, the paper’s front page captured on screen is a close replication of Imroze’s only available edition.

But not every time do our films take the effort to be convincing or detail-oriented. There are plenty of instances where shabbily designed pages with mastheads of popular newspapers slapped on them are passed off as ‘newspapers.’ As are shots of dailies where a headline is only altered to announce the required information while the rest of the page remains as is. This move produces curious scenarios. Like in ‘Hamraaz’ (1966), the brutal murder of the film’s heroine becomes the front page headline with the details of the then government’s new Finance Bill attached below. The Indian Express ‘front page’ that declares a millionaire’s reunion with his missing son in ‘Zameer’ (1975) can be called a large printout at best. The cheeky newspaper clipping in the end credits of ‘Main Hoon Na’ (2004) that went viral is another example.

Perhaps the most hilarious exhibit of this gimmick happens in the Shah Rukh Khan-starrer ‘Zero’ (2018). The misbehaviour of the film’s protagonist, a foul mouthed, vertically challenged man gets reported in the newspapers. One headline screams Bachche ki shakal mein shaitaan whereas the story’s body copy underneath it describes a potential meeting between the prime ministers of India and Pakistan.