Creative people are always asked if life inspires art or if art inspires life. The question becomes especially relevant as the country reels under a never-ending series of sexual crimes.

Indian cinema has always shown deep bias for patriarchal notions, and the Kannada film industry is no exception. Whether it is the symptom or the cause, the shortcomings of the Kannada industry have relegated the woman’s point of view to ‘alternative’ films.

Even more alarming is the glamourising of rape. Like other trends, the rape scene was an import from Bollywood, says well-known film critic K Puttaswamy, whose history of Kannada cinema won him a national award.

“It was Bollywood’s way of portraying sensuality and bringing in audiences,” he says.

Hindi cinema in the ’60s and ’70s started with ‘cabaret dancers’ such as Helen and Padma Khanna.

When ‘Husn ke laakhon rang’, from ‘Johny Mera Naam’, became popular, it became a benchmark that other south-Indian sought to follow.

In the ’70s, Radha Saluja features in a lengthy rape scene in ‘Do Raha’. Even though the movie did next to nothing for the actors, it inspired many from that era to use rape to portray sexuality.

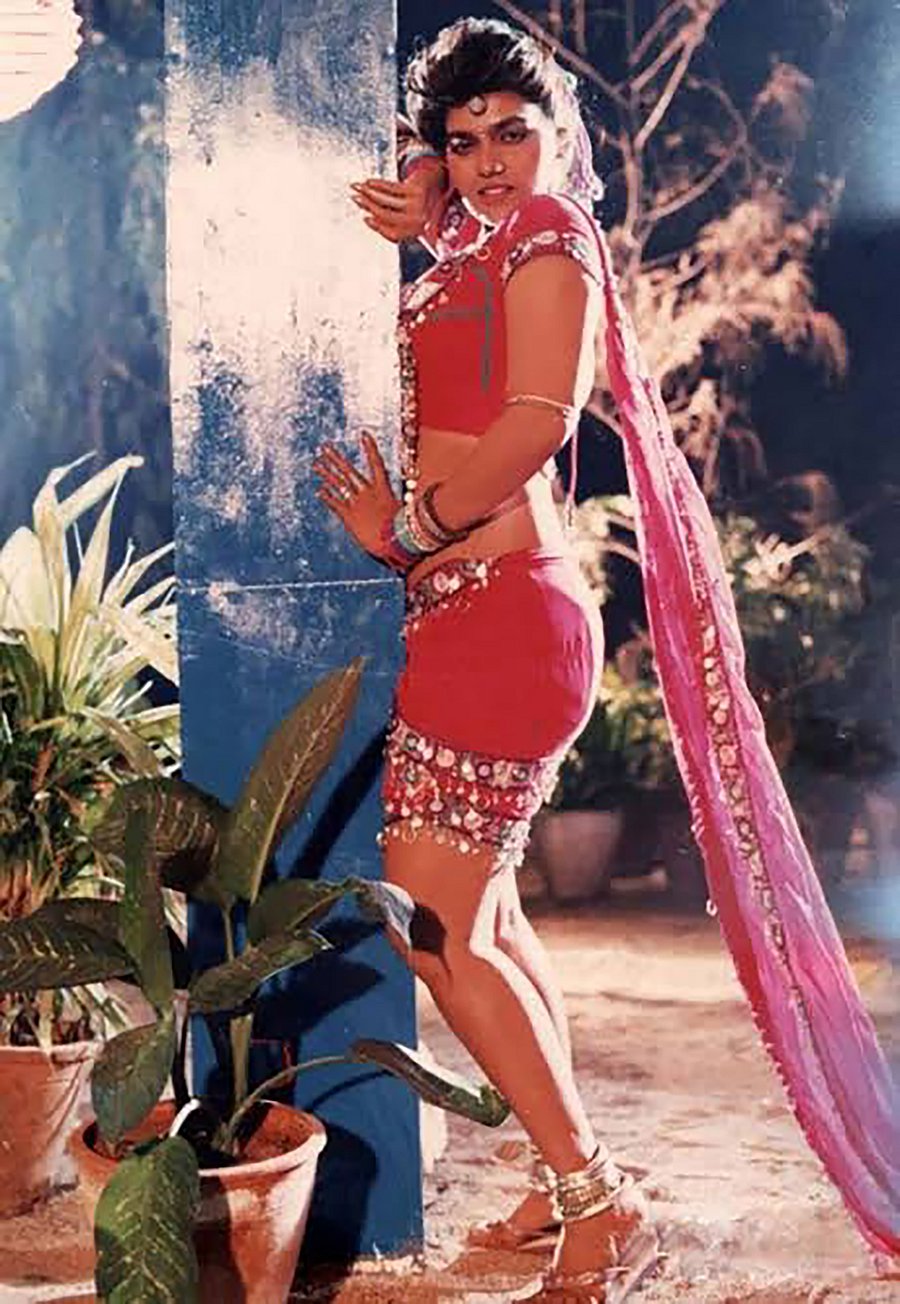

The Kannada film industry was no different—it had its share of dancers like Jyothilaksmi and Vijayalakshmi and a rape scene in many movies produced in the ’90s.

Even though the industry has considerably moved away from rape scenes, films like ‘Dandupalya’ and ‘Ragini IPS’ continue to cater to the male desire to see rape scenes. The audience has come to accept and anticipate scenes that perpetuate dangerous stereotypes for women.

Shaping culture

Many young women who grew up when Vishnuvardhan’s Naagarhaavu (1972) was released, and even college students to this day, can attest to having been harassed with Ambreesh’s ‘iconic’ “Aye Bulbul maathadkilva?” (Aye Bulbul, won’t you talk to me?).

Aishwarya Shet, development professional, remembers when she was in college, three years ago, she was teased with this dialogue. “I was taken aback and I remember the moment vividly,” she says.

Arpana Natraj, film enthusiast, gives an explanation for this: “At that time, when Ambareesh was the villain, people might not have wanted to imitate his behaviour, but as

he shot to fame as a hero, his problematic portrayals were whitewashed.”

Ambareesh as Jaleel in ‘Nagarahaavu’ was not a one-off portrayal; stalking is a norm. In fact, in 2013, Darshan was the protagonist in ‘Bulbul’, and predictably the ‘catchphrase’ of the movie was Ambreesh’s iconic dialogue.

Arpana brings to the fore an interesting dichotomy: “When a villain is involved in harassment and stalking, it is bad, but when the hero does it, it is accepted as normal.”

She cites the example of ‘Appu’, in which Puneeth Rajkumar is obsessed with Suchitra, played by Rakshita, and spends more than three-quarters of the movie stalking her and not taking ‘no’ as the answer.

In a country that does not understand consent, this trope sets a dangerous example, blurring the boundaries of consent. It implies that a ‘no’ is a ‘no’ only until it can be turned into a ‘yes.’

Another concern is the portrayal of women. Since the film industry is dominated by men, with very few women working behind the scenes, the roles women are offered are often not well-rounded.

The chief role women play in popular Kannada cinema is that of a love interest. Whatever problematic behaviour the hero displays does not matter as the heroine is destined to fall in love with him and forgive his behaviour anyway.

The power to control

Much of Indian cinema is realised in the male gaze. Laura Mulvey, feminist film critic, says gender power asymmetry is a “controlling power in cinema.”

Those who control how the story is told are the ones manning the camera, and the ideologies of the men on screen are those of the men watching it.

If popular cinema is directed by men, watched predominantly by men and made by men, then most movies tend to focus on the female body.

Mansore, director of ‘Naaticharami’, a film told from a female perspective, says, “It is also important how the shot is framed. Many shots that introduce or focus on women, focus on parts of their body.”

This is especially evident in Kannada songs like ‘Sonta Sonta’ (waist waist) from ‘Chandu’, featuring Sudeep. The camera almost exclusively focuses on the waists of women who gyrate to the beats of the song.

‘Madhyarathrilli’ from ‘Shanthi Kranthi’ by Ravichandran is another example. The song is a choreographed sequence that follows Juhi Chawla after she gets off a bus, late at night. She is hounded by at least 50 men, who she fights off with her bags— until Ravichandran swoops in and saves her.

“I can’t believe there were so many people recruited to do this song and think it was okay,” says Arpana.

The song makes a comedy out of potential sexual violence and is a tool to portray the protagonist as the saviour.

Silver lining?

Such films have normalised behaviour that we would otherwise find repulsive.

Mansore says, “when you are looking at cinema as business, it is easy for directors to be a bit formulaic—they are trying to please the lowest common denominator, so they go with what they think works. The problem is we are not asking about their ethical implications.”

Abhay Simha, director of Paddai, says, “As long as the audience continues to watch films like these, directors are going to make them. It is wrong without a doubt, but they are looking for a return on investment.”

Is this what the people want, or are they only consuming what is available? Many directors say the audience was more open to female-oriented films in the late ‘80s.

With the advent of ‘Premaloka’, the early ‘90s became a turning point for how the woman was portrayed, and the audience loved it.

“The Kannada movies I watched as a child were completely different,” says Roopa Rao, director of ‘Gantumoote’, which received critical acclaim for representing the female gaze.

“People are becoming open to such movies again,” she says.

However, popular cinema is another beast, and while directors place the onus on the audience, and the audience places the onus on directors, the first step towards a more respectful culture seems far away.