When screenwriter John Ridley pitched “The Other History of the DC Universe,” a five-part comic book series that looks at pivotal events through the perspectives of several nonwhite DC heroes, he knew Black Lightning would be at its centre. Ridley was 11 when he met the hero in 1977.

“This was a Black man who ostensibly looked like me with his own series,” Ridley said during a recent interview. An added bonus: “He was a teacher in his secret identity as Jefferson Pierce, the way my mother was a teacher.”

The chance encounter, Ridley said, was profound and far-reaching. Tony Isabella, who created Black Lightning, “had no idea he was inspiring me — literally inspiring me — to become a writer.”

Ridley’s career includes writing for television and film, which earned him an Academy Award in 2014 for Best Adapted Screenplay for “12 Years a Slave.” But he is no stranger to comics. He wrote “The American Way,” which was published in 2006, about a group of heroes in the 1960s and their reaction to a Black member joining the team, and a sequel in 2017.

The first issue of “The Other History of the DC Universe” will be released Tuesday. He is also working on a comic, to be published in January, that features a nonwhite Batman.

“Other History,” which is drawn by Giuseppe Camuncoli and Andrea Cucchi and painted by José Villarrubia, begins with Jefferson Pierce and reads like a journal of his most private thoughts. Readers learn about his family and see him become Black Lightning. They also get his views on some of DC’s champions, including John Stewart, who became a Green Lantern in 1971 and has been regarded as the company’s first Black superhero, and the original Justice League, whose members Ridley pointedly noted were predominantly white men.

Subsequent issues will spotlight other characters and will conclude with Anissa Pierce, one of Jefferson’s daughters, a heroine known as Thunder.

In a recent telephone interview, Ridley talked about “Other History,” the new caped crusader and why the representation of nonwhite heroes matters. The conversation has been lightly edited.

NYT: Were you a comics fan growing up?

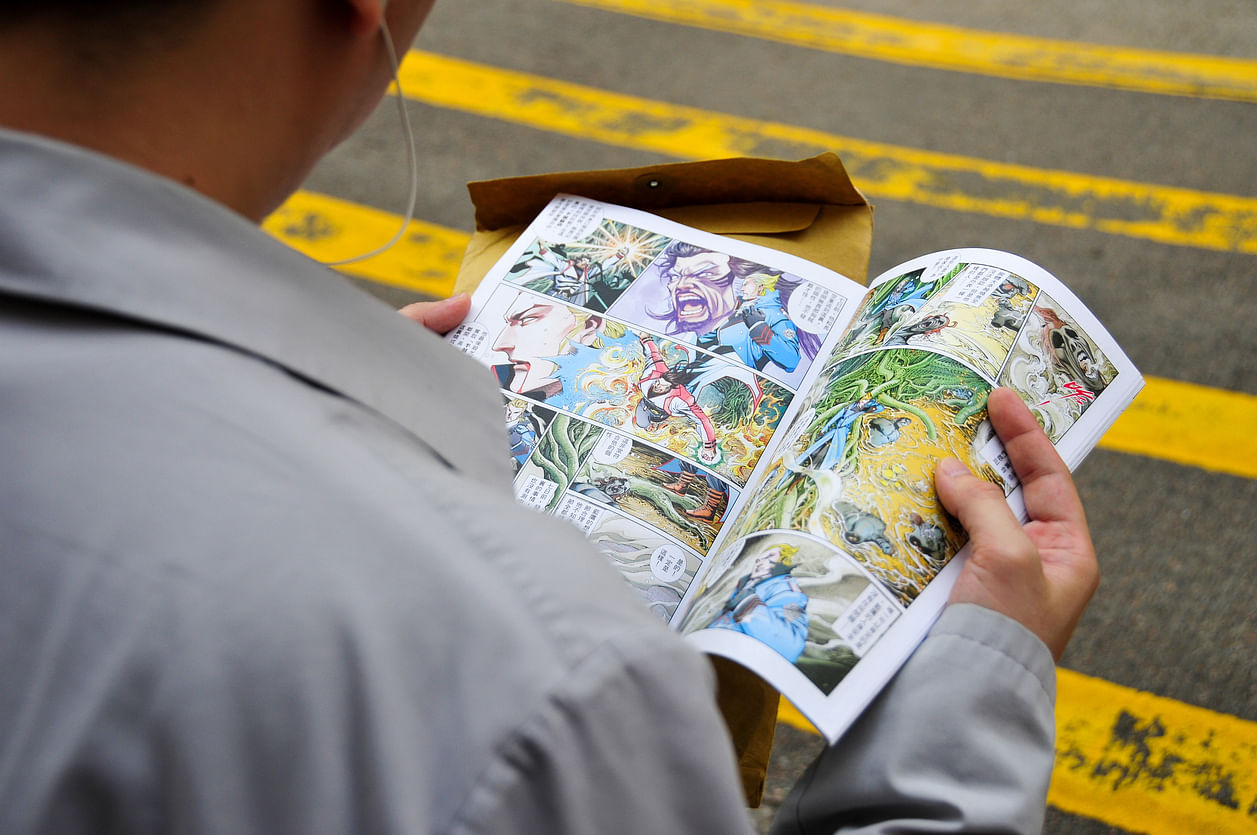

JR: Within reason. There was a time when I hated reading. One day my parents shoved a comic book in my hand, probably to keep me occupied, and it was the first time I really started reading.

It was the combination of words that were slightly above my reading level at that time and these images that were fascinating. The first comic that I read was actually kind of graphic for that time period. It was a World’s Finest comic where Superman and Batman wound up in a gulag. It was this story that was not quite heroic and very current and dealt with politics. It had far more impact on the kind of stories that I tell than I would have known.

NYT: Were you familiar with Black Lightning and his backstory?

JR: I remember when Black Lightning came out. I remember pulling that issue out of this brown paper bag and being blown away. And the story wasn’t just about fighting super villains — it was about fighting for your community, fighting to make sure students got the quality education they deserved. I still have that very first issue.

NYT: Jefferson has some tough feelings about John Stewart, who is considered DC’s first Black superhero.

JR: Sometimes the hardest expectations to square are the ones from our own community. We expect for us to see the world or certain struggles the same way. That’s just not true. And it’s also not fair to us. We certainly have to be there for each other, but we have to be individuals.

I want to honour the canon, but at the same time, I am expressing a very particular version of these heroes. I wanted them as two men of colour to have a moment just as men, particularly as Black men, where they engaged. They share tragedy and loss. And how they felt about each other was maybe different from the reality of where their relationship needed to be.

NYT: Jefferson also has pointed views on Superman. Did you get pushback?

JR: No, because it is not about Superman being a bad guy. We visit Superman and other heroes through the lens of these characters. Even though Superman is an immigrant and truly an alien, his passport is stamped because of the way he looks and because of the way he presents himself.

All of these characters have to reconcile how they view other people and whether they’re being fair. If I made Superman or Batman or Wonder Woman bad people, I’m sure we would have had pushback. But it was all fair game if it came from a perspective that felt real and grounded.

NYT: How did the project initially come together?

JR: I was very nervous when I pitched it. It was a kind of arrogance, maybe, to come back and say, I want to look at your entire history and shift the lens a little and have some real talk about some of these characters. To their credit, DC saw the value. This was long before the current reckoning on race and representation.

When you’re dealing with stories about race, otherization, people outside of the prevailing culture, unfortunately, it’s going to be relevant almost any time it comes out.

NYT: Let’s talk about your upcoming Batman comic and your tease that it would highly likely be a nonwhite Batman.

JR: Let me confirm that it is definitely a Black person under the cowl. It was an off-the-cuff line, meant to be humorous. Comic book fans are the best fans. They will go through everything and check it and recheck it. It was the quip heard around the world. Definitely, without a doubt, the next Batman is a Black Batperson.

NYT: I love that you’re saying “person” and not “man.”

JR: I have to have what fun I can. There’s no reason in the modern era to think that the person who is representing Batman is a man. But whoever it is, it is an interesting opportunity to populate the world around this new Batman. We’ll have some interesting characters coming in and a lot of representation. It was really important to make sure that this Gotham City was well represented.

NYT: Have you gotten any negative reaction to the focus of these stories?

JR: I’m not on social media. I don’t spend a lot of time parsing what others say, and by the way, they have a right to say it. It’s part of the fun of being a fan. Look, it is the absolute truth: You cannot please everybody. I have an audience of two. I have my two boys. This is the first time that I can recall they’ve been genuinely excited about my work.

They appreciate the things that I do. They’re happy for me. They’re great supporters. But they would much rather see “Black Panther” than “12 Years a Slave,” let’s be honest. So to be able to write the next Batman, for them to know that this next Batman is going to be Black, everybody else on the planet can hate it, have a problem with it, denigrate it, but I have my audience and they already love it.

NYT: Do you read a lot of comics? Representation has certainly increased since we were kids.

JR: It has. I certainly don’t read as much as I did up until I was about 30. I still buy probably too much. My wife is a little like, “it’s OK to grow up at any moment.” There’s so much more representation than when I was growing up, but is there ever enough? When you talk to a young Latinx, they’re going to say no. If you talk to someone from the LGBT community or young Black people or young women or people of any age who are looking for inspiration, there is never going to be enough.

But there’s more, and more importantly, not just on the page, but the folks behind the scenes: the writers and artists making the stories. It’s great to have more representation. When you create it, it’s an invitation to people to join in — with their time, their money and sometimes with their talent. I’m more excited about the representation that these companies are trying to carve out behind the scenes because that’s the biggest difference.