“What’s in a name? That which we call a rose by any other name would smell as sweet,” said Juliet, referring to her lover Romeo in the famous Shakespearean tragedy that bears their names. This is a deep question, but it is common practice to use that first sentence in a frivolous manner.

The phrase, “A rose is a rose is a rose,” poses a similar problem. It is about the ‘problem of universals’ or the human tendency to generalise, but is trivialised to play down characteristics seen as unique.

In recent months, two Tamil films have brilliantly educated the audience about the significance of names.

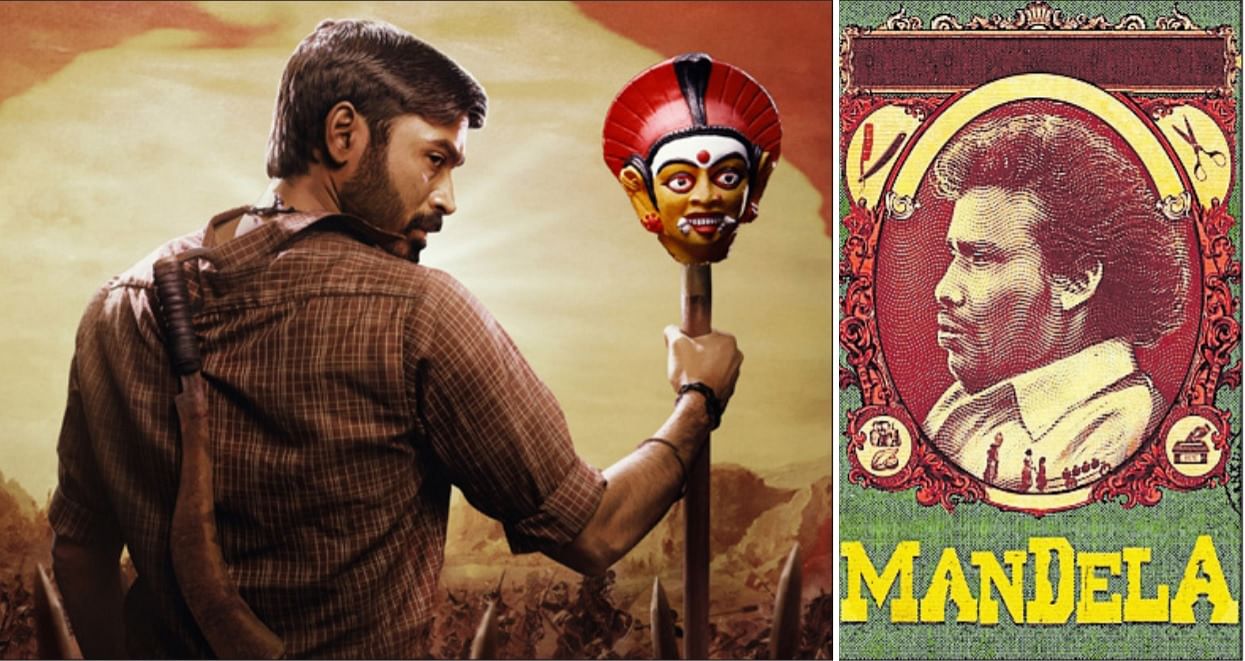

Mari Selvaraj’s sophomore film ‘Karnan’, starring Dhanush, woke us up to the upper caste prejudice against lower caste names like Duryodhana and Abhimanyu. Madonne Ashwin’s ‘Mandela’, a satirical take on caste politics, effectively uses the name as a plot device.

Tamil cinema of the ’90s was accused of using caste in titles and themes irresponsibly: ‘Chinna Gounder’ (1991), ‘Thevar Magan’ (1992), ‘Ejamaan’ (1993), and ‘Nattamai’ (1994) are commonly cited examples. All of them escaped the caste groups’ radar when they were released.

However, in 2004, Kamal Haasan wasn’t that lucky with ‘Virumaandi’, originally titled ‘Sandiyar’. A video of an allegedly drunk Kamal ranting about the trouble he faced went viral. The film eventually achieved cult status.

Controversy greeted Pa Ranjith when he made ‘Attakathi’ (2012). He is hailed as the pioneer of an important movement in Tamil films. Selvaraj, his protege, similarly champions identity pride with his debut ‘Pariyerum Perumal’ and now ‘Karnan’.

In Telugu cinema, ‘Samarasimha Reddy’ (1999), ‘Narasimha Naidu’ (2001), ‘Chennakeshava Reddy’ (2002), and ‘Bharata Simha Reddy’ (2002) all went through just fine with nobody raising an eyebrow about the caste-obvious film titles.

Earlier, Indrasena Reddy (starring Chiranjeevi) and Aadi Keshava Reddy (Jr NTR) were reduced to just the first names.

In that era, utterly insensitive and superficial films that glorified violence and masculinity were made, claiming they portrayed the feudal wars in the Rayalaseema region.

Ram Gopal Varma, who unfortunately has reduced himself to a satirist, made ‘Kamma Rajyam Lo Kadapa Reddlu’ (2019), an in-your-face political satire (or parody, only he knows), which, after the Censor Board’s intervention, was renamed ‘Amma Rajyam Lo Kadapa Biddalu’.

The new name did rhyme well with the original and circumvented the caste controversy. But is that enough to earn a clean chit?

The Telugu film industry continues to deliver films titled ‘Arjun Reddy’, ‘George Reddy’ and ‘Sye Raa Narasimha Reddy’ but at least the justification, although not fully convincing, is better now.

Although many Malayalam film titles refer to a religion, they don’t seem to land in controversy, perhaps because of the first-name hack.

Apart from the rare cases of ‘Veerappa Nayaka’ (1999) and ‘Kempe Gowda’ (2011), there are very few Kannada films that fall under such a category.

A film’s title (and theme) is not a topic for a right-wrong, fact-fiction debate, instead the question is about sensitivity — both of the filmmaker and the audience.

(The author is a freelancer who writes on films and entertainment).