Published in 1965, “The Autobiography of Malcolm X” was not, originally, Malcolm X’s idea.

But in 1963, Alex Haley, a writer who would later win the Pulitzer Prize for “Roots,” convinced his skeptical subject to share the story of his life. During all-night interviews in Haley’s cramped Greenwich Village studio, Malcolm X recalled his upbringing in Omaha, Nebraska, by parents who decried racism and supported Marcus Garvey’s Black nationalism; his turn to hustling and crime as a young man in New York City; and how he found, was transformed by and eventually departed from the Nation of Islam.

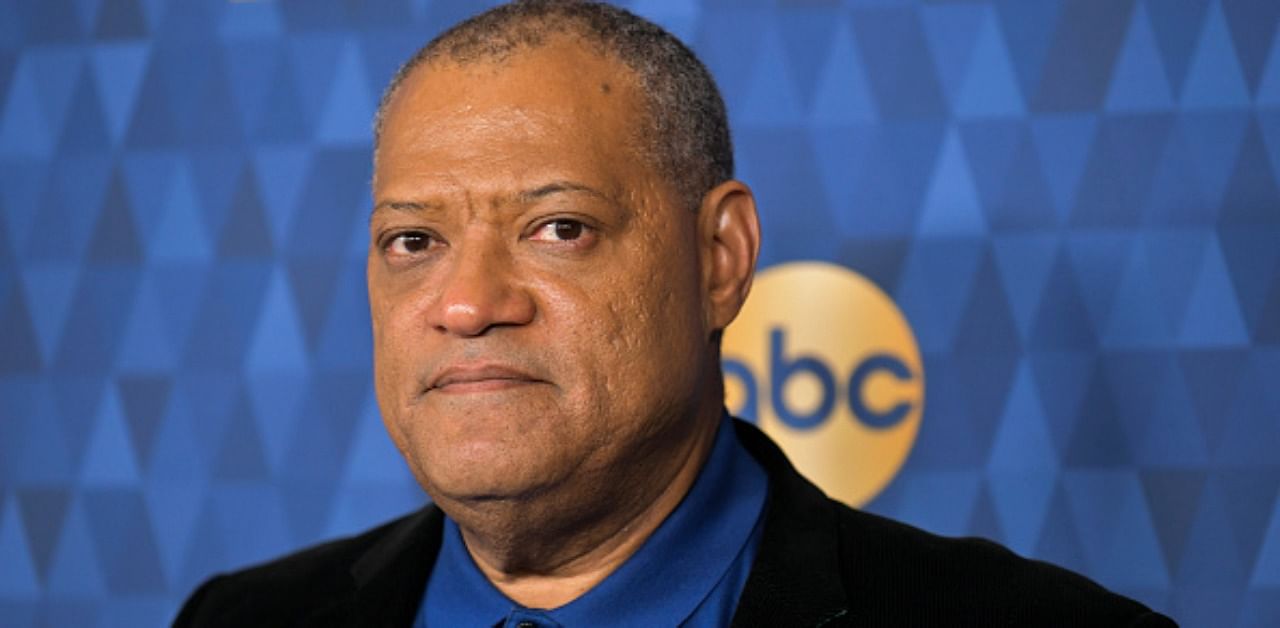

The resulting memoir has become a foundational document not just in the history of American civil rights, but in 20th-century thought. Asked to narrate its first-ever unabridged audiobook recording, which Audible will release Sept. 10, Laurence Fishburne — an Oscar-nominated actor whose roles have included Nelson Mandela and Justice Thurgood Marshall — knew he had a tall order ahead of him.

“I don’t think Malcolm was all that trusting of Alex Haley in the beginning,” he said in a phone interview from his home in Los Angeles. “He had to earn his trust.”

But this narrative is a testament to the intimacy they developed over time. “If I’ve done my job well,” Fishburne said, “the listener will come away feeling as if they’re Alex Haley, and Malcolm is speaking directly to them.”

This interview has been edited and condensed.

Q: In your 50 years as an actor, this is your first audiobook role. How did the format compare to performing on the screen or the stage?

A: It’s great. Once upon a time in this country, there was this thing called radio. I liken Audible to radio theater. It’s the reader and the listener engaged in this experience together.

Q: And of course, none of us are able to go to any kind of theater right now.

A: No, but you can be in the theater of your mind.

Q: You’ve said this role presented a “heavy responsibility” for you. What did you see as your greatest challenge in taking on this project?

A: Trying to capture the essence of a personage like el-Hajj Malik el-Shabazz [the name Malcolm X adopted in 1964 when he left the Nation of Islam] is very, very big. He was a larger-than-life figure. As he was greatly loved, he was also greatly misunderstood. The responsibility I felt was to try and illuminate his humanity as much as possible.

What a gift he gave all of us in the way in which he lived his life. To have the foresight to record his experiences here on Earth with the clarity that the had, after growing up the way he did, in that time and place and under those circumstances; after his experiences as a criminal living outside of the law, being incarcerated; being inspired and enlightened and liberated by the honorable Elijah Muhammad and Islam; and then having a change of mind about the world and the way in which he could be a part of changing it for the better. He was really an extraordinary individual. With every chapter of the book he becomes more and more human.

Q: You began recording it before George Floyd was killed, before this year’s Black Lives Matter protests. What was it like to perform Malcolm X’s words in the new context of the civil rights movement today?

A: The timing of this audiobook doesn’t change my perspective so much as it amplifies it, and brings it into clearer focus. This has been the major theme of my life’s work: the struggle of African American people to be treated as first-class citizens in this country. When I started doing “Blackish,” the question I’d often get would be, “Why is it now that people are ready for this kind of show?” And I used to say, “Well, you know, I’ve been Black all my life.”

I was asked to read his book almost 30 years ago, and for reasons beyond my understanding that didn’t happen. Evidently the time is right. I just feel doubly blessed to have been asked to read his book at this moment.

Q: How did you tackle the difficulty of mirroring the escalation in Malcolm X’s tone, as a man and as a narrator, over the course of the book?

A: I was blessed with a gift for the dramatic art. So my job is just to use my instrument in the service of Malcolm, the brilliant thinker and political activist, and of this brilliant writer, the wordsmith Alex Haley.

The other secret weapon is Nicole Shelton, our director. She was my audience, and she was not just an avid listener, she was an active listener. She would stop me if even an inflection was a little wrong, and we would go back over it. We went back over things many times to get them right.

Q: When you were growing up, your father was a prison guard. How did your own upbringing impact your reading and perception of the police brutality in this book?

A: Yes, my father worked with juveniles in the correctional system in New York City. His brother, my uncle, was a beat cop for years, and then he became a detective. The stress of the job was unreal — my uncle died of a massive heart attack at the age of 49, and I think most largely due to the stresses of the job. My relationship to them, and to their father, my grandfather, who was also a civil servant — he was a postal worker — gave me a clear understanding of what was permissible and what was not. There was only a certain amount of trouble I could get into, let’s put it that way.

Q: Can you remember the first time you read this autobiography?

A: I remember reading this book when I was in my early 20s and feeling inspired by his journey. Someone who was so steeped in criminality, to be incarcerated as a result of a life of crime, and to use your incarceration to educate yourself? To come out a wiser, more well-spoken, thoughtful man — a full-grown man — with not just a fire in his belly but a real sense of mission to galvanize people, to open their eyes? That’s really, really inspiring.

Q: Here’s an unanswerable question for you: Do you think society has made progress since 1965?

A: That’s a very good question. If I were to ask you that question, what would you say?

Q: I would say not enough.

A: Right, so we can say that the answer to that question is really yes and no. We still live under systemic racism in this country. That is a fact. That has not changed. Things have changed within that system, but the system itself has not changed. And hopefully we are in a moment — and this is partly why this book is so important now, and why it may have the ability to effect more change — where it seems that more people are aware of just how much change needs to happen, and are willing to do what is necessary to create it. And that’s where things have changed.