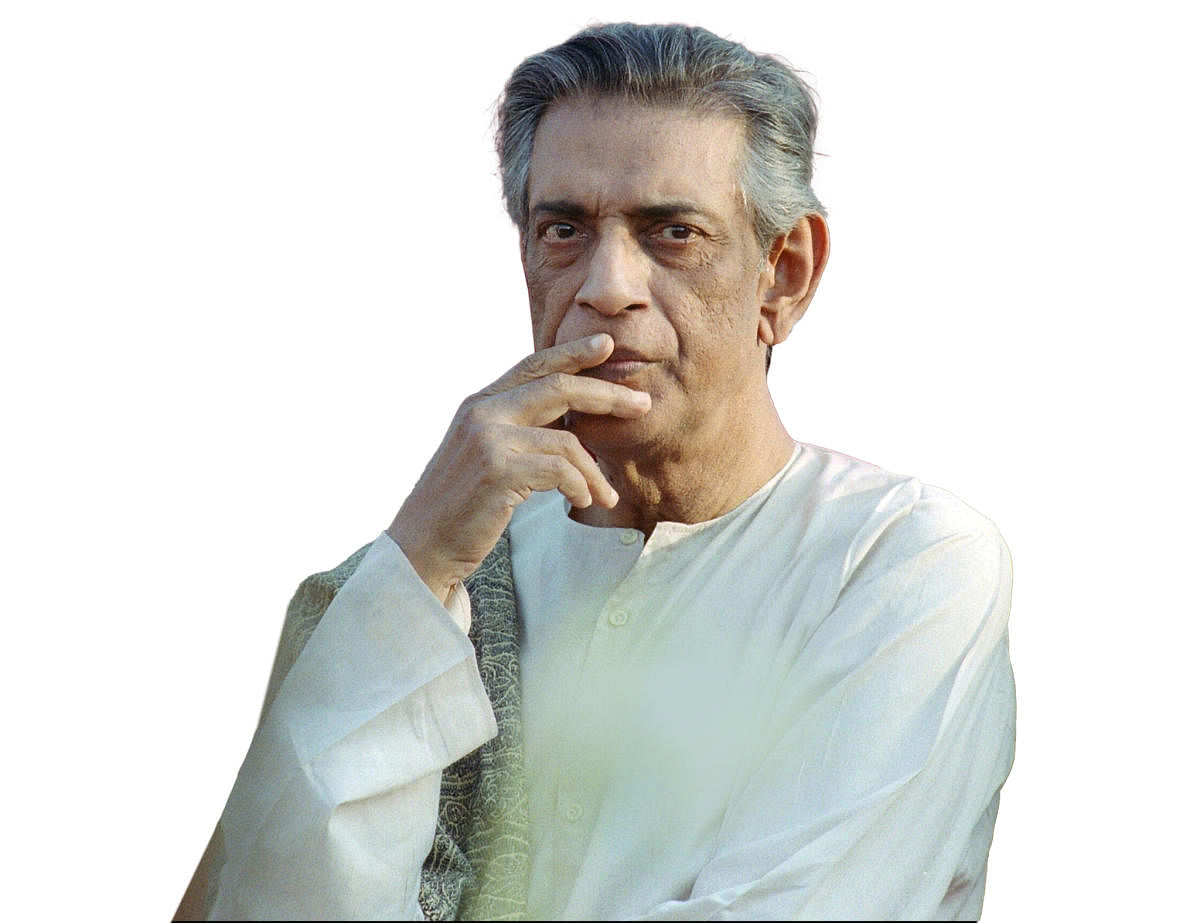

This year is the centenary of Satyajit Ray’s birth and his admirers are celebrating it in a vociferous way, but often without understanding the reason for his importance as a filmmaker.

Ray, it must be emphasized, was not the forerunner of Indian art cinema. He was a filmmaker who took his place in the first line of cinema from the newly independent former colonies and a cultural giant of the Nehru era. Indian art cinema is a product of Mrs Gandhi’s cultural interventions around 1970.

One of the first questions asked about Ray is whether he was truly Indian or western in his methods. The answer to this is in two parts: in the first place, since the camera has the propensity to catch what is before it, his recreation of reality was authentically Indian, and 'Pather Panchali' makes that evident.

Secondly, his cinema adopted a mode of narration not typical of Indian cinema. His films, while exemplary in their narrative strategies, have not been imitated by artists in Indian cinema. He is not a difficult filmmaker to study, understand and mimic but hardly anyone has done it — perhaps because of the Indian mindset being antithetical to mimesis. Mimesis is the tendency of art to imitate the perceptible world in order to represent it.

If one studies Indian popular cinema closely, one realises that it is not mimetic. The earliest cinema was the documentary (by the Lumieres) and the one following it was fantasy (George Melies). These two went on to become the two components/polarities of cinema — catching reality through a mechanical device and expressivity and interiority using set design, performance and montage.

But when Indian cinema arrived through DG Phalke, it avoided both courses and took the line of the mythological ('Raja Harishchandra'). Phalke insisted that his film was ‘realistic’, i.e.: it was bringing to life a truth everyone recognised. Rather than represent the world perceptible to the senses, it tried to represent underlying ‘truths’ directly.

When popular cinema left the territory of the mythological and embarked upon ‘socials’ the content of the films was still familiar ‘truth’. Popular cinema told stories relating to ideals and archetypes ranging from ideal love to archetypal mothers-in-law — played by Lalita Pawar.

With technology becoming sophisticated these ideals remain intact, cinema relaying durable messages. It could pertain to the ideal family in which the young are obedient as in 'Hum Aapke Hain Koun' or the genius whose achievements belie effort as in '3 Idiots'. The messages are variable but they are presented (even when they contradict each other) as the ‘truth’.

Art cinema is not different: where popular cinema dealt with ideal friendships (as in 'Sangam' or 'Sholay'), art cinema dealt with the decadent bourgeoisie capitalists and the solidarity of the working class (as in the films of Mrinal Sen) or religious tolerance.

The messages change as do the types relaying them but they remain ‘messages’ purveying some ‘truth’, even if it is the brutality of the police (as in 'Visaranai'). There has been the occasional other filmmaker who does not fit the ‘purveyor of truth’ model — Ritwik Ghatak, G Aravindan, Adoor Gopalakrishnan — but Ray was the only one to systematically base his films on observation rather than apriori conclusions, with the exception of a few films like 'Sadgati'.

To point out Ray’s difference, a strategy used by Indian art cinema to relay messages is for a focal character to go through an awakening, as for instance the lawyer in 'Aakrosh' or the wife in 'Umbartha'. Take the boy in 'Ghatashraddha', who awakens to the cruelty of traditional patriarchy or the boy at the conclusion of 'Ankur' who flings a stone at the landlord’s window. If one were to compare these films with 'Pather Panchali', there is no similar ‘awakening’ that Apu goes through.

Ray’s best films, in my view, are 'Pather Panchali', 'Jalsaghar', 'Charulata', 'Shatranj Ke Khiladi', and 'Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne'. They tell stories effectively without relaying messages. The stories are rich in character and situation and draw on historical context without expressing hallowed sentiments. 'Shatranj Ke Khiladi', for instance, is not appreciated because it is not ‘patriotic’ (like 'Mangal Pandey') but Ray is being true to history since the nation did not exist even as an idea at that time.

Premchand, on whose story the film is based, is, on the other hand, preachy about the conduct of the aristocracy. Similarly, 'Goopy Gyne Bagha Byne' may be the only non-preachy children’s film ever made in India since it respects the child’s imagination instead of yielding to the parenting impulse and relaying suitable messages either about heroic children fighting villains or about bringing them up correctly ('Taare Zameen Par').

Ray’s narrative strategies become quite clear as one watches his films, his attention on detail not directly leading to a message, which makes them very engaging. It is as if his admirers do not know how to watch his films. If they had done that, there might have been others following in his footsteps. If Ray is admired internationally more than any other Indian filmmaker, it is with good reason.

(The writer is a well-known film critic).