India is justifiably proud of its robust, egalitarian and far-sighted Constitution, which has stood the test of time over the past seven decades and repeatedly rescued our democracy from falling into an abyss of uncertainty and chaos.

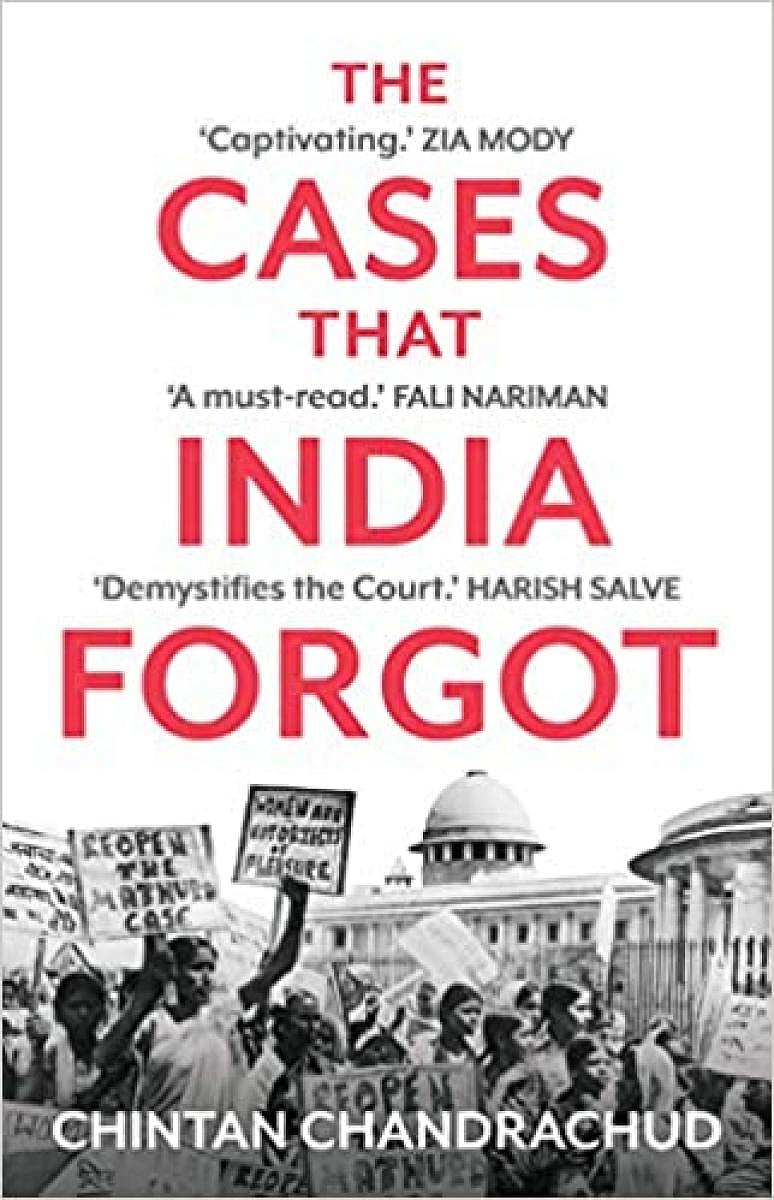

Whenever the citizenry or elected representatives have tried to go astray, the judiciary has stepped in firmly to bring them back onto the right path. There have been a number of path-breaking judgments, especially of the Supreme Court, which are widely quoted for having enhanced the scope of the Constitution. In this context, Chintan Chandrachud, who is an associate at the London office of Quinn Emanuel Urquhart & Sullivan, has authored a book titled, ‘The cases that India Forgot’, which chronicles 10 interesting cases that may have faded from public memory, but are no less significant.

Failed to live up?

The general perception is that the constitutional courts in India have acted as a bulwark against ‘the indiscretions and misadventures of the parliament and the government’, but Chandrachud, the grandson of a former Chief Justice of India, through this book, points out that there have also been several occasions when the courts have failed to live up to their reputation.

The author has picked on three interesting constitutional matters, which severely tested both the courts and the parliament, highlighted the interplay of their respective jurisdictions and through the eventual outcomes, contributed significantly to the evolution of our democracy. In less than two years after India became a Republic, the question of reservation, which was already in force through ‘the communal G.O. of 1919’, became a contentious issue as it seemingly violated two fundamental rights of the newly-enacted Constitution. Eminent lawyers and judges of the time racked their brains on the issue, and finally, when the Supreme Court upheld the Madras High Court’s decision striking down the reservation, there was widespread agitation and protests from the people.

With the impending general elections of 1951, the Jawaharlal Nehru government came out with an amendment stating that “neither Article 15 nor Article 29(2) would prevent the State from making special provisions for the educational and social interests of the backward classes,” and doused the fire.

Power and privilege

The famous Keshavananda Bharati case of 1973 is often referred to as the one that settled ‘the battle for custodianship of the Constitution’ between the parliament and the judiciary.

However, Chandrachud points out that the then prime minister Indira Gandhi not only upturned the Keshavananda Bharati judgment, but also ran roughshod over the judiciary and passed the 42nd amendment during the Emergency, making it clear that parliament had the power to amend any part of the Constitution and such amendments “would not be called in question in any court, on any ground.” The judiciary’s supremacy was restored with the subsequent Minerva Mills Vs Union of India case, thanks to the ingenuity and brilliant argument put forward by eminent jurist Nani Palkhiwala.

On matters of powers and privileges of the State legislatures and also resolving the contentious issue of government formation after a split verdict, we have seen, of late, the elected representatives dutifully accepting court directives, but it was not so simple earlier. The author narrates one of the earliest tussles between the legislature and the judiciary on the question of ‘breach of privilege of the legislature’, which resulted in a high-voltage constitutional crisis.

Right interventions

In the Keshav Singh case, which originated in the Uttar Pradesh Assembly, when the legislature tried to assert its supremacy by ordering the ‘arrest’ and production of two high court judges for questioning its privilege, the court hit back with a unanimous order by all its 28 judges daring the legislature to act against them. The judiciary ultimately prevailed with the Supreme Court ruling that the “Assembly resolution was an affront to the judiciary.” The author concludes that this case demonstrated how ticklish legal problems are best solved through statesmanship rather than brinkmanship. In the Rameshwar Prasad Vs Union of India case involving the Bihar Assembly and the then Bihar Governor, Buta Singh, when the people’s verdict was sought to be subverted by using the office of the President of India, the Supreme Court intervened decisively to end such manipulations.

Chandrachud’s concern for personal liberty and human rights is deeply etched in his engrossing narration of the courts’ handling of the Adivasi woman Mathura’s rape case, senior civil servant Rupen Deol Bajaj Vs KPS Gill case, the TADA case, the Armed Forces Special Powers Act (AFSPA) case involving the Northeast and the Salwa Judum case of Madhya Pradesh. In each of these, he points out that the courts erred on the side of conservatism and pronounced judgments largely “abdicating their responsibility.”

And yet, in the final analysis, it needs to be emphasised that if the Indian democracy has survived many ups and downs, the judiciary has undoubtedly played a pivotal role.