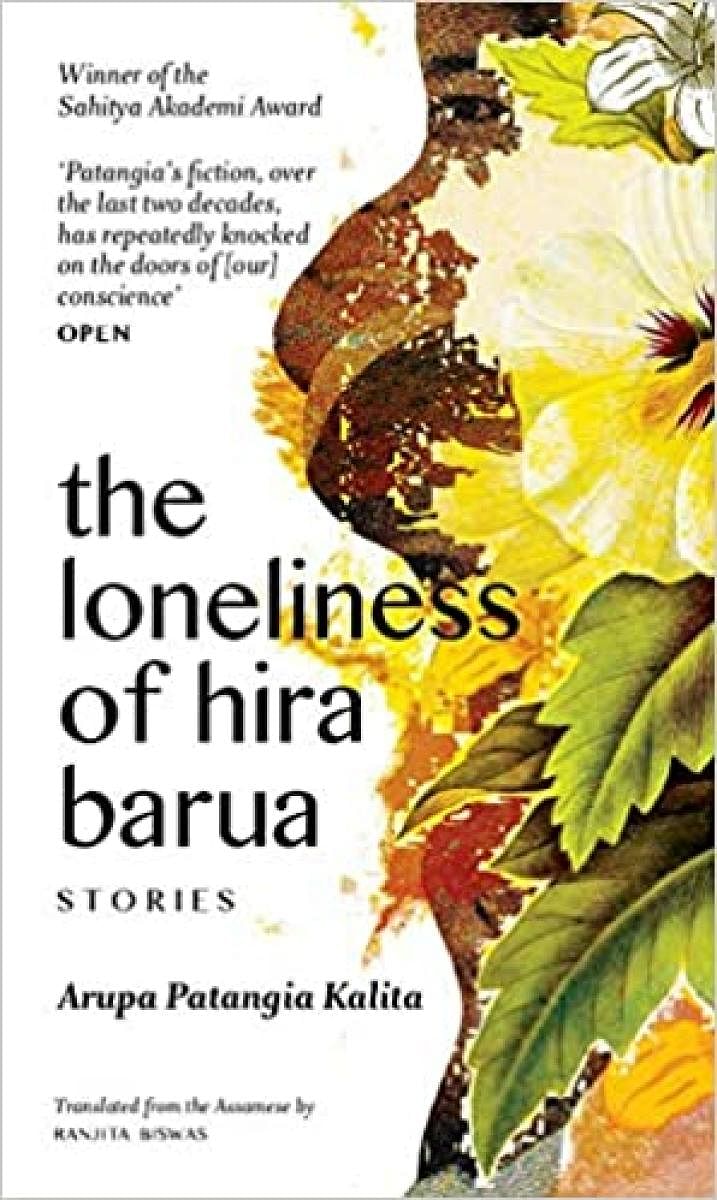

Whenever a magazine or a newspaper publishes a list of must-read books/writers on/from India, there is a tendency to leave out those from the North East. On the rare occasions they are included, usually, the ones writing in English get mentioned. In this context, it is heartening to see the English translation of Sahitya Akademi award winning short story collection of the Assamese writer Arupa Patangia Kalita. Like several other eminent Indian vernacular writers of the 20th century, novelist and short story writer Kalita, also has a doctorate in English literature and taught English till her recent retirement.

The loneliness of Hira Barua is an eclectic collection of stories of dreams, aspirations and sorrows of the ordinary people of Assam, where one cannot live untouched by the violence caused by the insurgency. Invariably, the narratives, which shift from the mundane to the violent, portray the impact of the identity politics of the troubled region on innocent lives. Like the story of the young ‘happy-go-lucky’ girl Mainao,“on the threshold of youth”, whose seemingly ordinary wish to visit the Durga Puja pandal in her newly woven Dokhana, leads to tragic consequences.

Beautifully etched

Kalita’s stories leave the reader with deep insights into the lives of women — young, old, middle aged — in Assam. Particularly interesting are the tales in the last quarter of the book, of middle-aged women such as Brinda Khuri from A Cup of Coffee and Mrs Chakraborty from Stream and Hira Barua from the title story. The daily lonely lives of these women are etched beautifully with great domestic details by the writer. Almost all stories have the violent politics of the Assam agitation as the background.

In what seems like an experiment with form, there are a set of shorter stories clubbed under one — No Escape from Hell. These tales are the tragic experiences of parents in the modern Assamese society whose children have gone down the wrong paths in life and rejected the values of their elders. Through the lives of these seemingly upright middle-class people, Kalita critiques the industrial pollution spoiling the pristine nature of Assam and modern fashion —imported from elsewhere — which the youth of the new era are obsessed with, and of course, the deterioration of moral values.

The innumerable culture details, especially the culinary ones, must have challenged the experienced translator Ranjita Biswas no end; she seems to have translated these challenges into an advantage by weaving her own beautiful prose in English without losing the vernacular flavour of the original. While these stories reveal to us the impact of the violence as a result of the identity politics on the Assamese society, one wishes there was at least one story, which could help the reader get a more deeper understanding of the motivations of the young to take up arms in the name of identity.

Through these stories, Kalita introduces Assamese culture to the reader — the food (Pitha, Bhorpitha, Joha rice, varieties of fish, poita-bhaat), the family systems, traditional clothing (Dokhana, Mekhela Sador) and the domestic life of the lower middle-class. There is a lot for the reader to unpack in the details and imagery described in these stories, which will certainly provoke him to read further about the colonial and political history of Assam.