Several decades ago, at a time when Carnatic music ruled the roost in sabhas across south India, an eight-year-old kid ascends the concert stage with the blessings of his guru. Seated across from a large gathering, he quietly bows to his guru, not noticing his father strumming the tambura with anxiety writ all over his face and begins to sing the varnam ‘Vanajakshiro’ in raga Kalyani.

He proceeds to sing the composition in all three speeds, wraps it up in style, bows once again to his guru, begins an alapana in raga Jaganmohini and moves into the Thyagaraja kriti ‘Shobhillu Saptaswara.’ The audience sits in a trans and before anyone could notice, three hours pass in a blur.

When the boy ends the concert with a ‘Mangalam’, his tearful guru rushes to the stage and embraces him lovingly with the realisation that he has “misjudged the talent and capability” of the little boy. Musanuri Suryanarayana Bhagavatulu, who was to follow the little boy onto the concert stage for his Harikatha performance, changes the content of his presentation, and inspired by the boy’s musical prowess, begins to analyse his genius. Not stopping with that, he renames the boy Balamuralikrishna from Muralikrishna, the name by which he was known after July 18, 1938.

From that time on, Balamuralikrishna’s genius was never in doubt. Even the most vocal of his critics (who were many) admitted grudgingly that he possessed a rare mix of musical comprehension, imagination and an almost magical rendition that kept audiences spellbound, no matter where he performed.

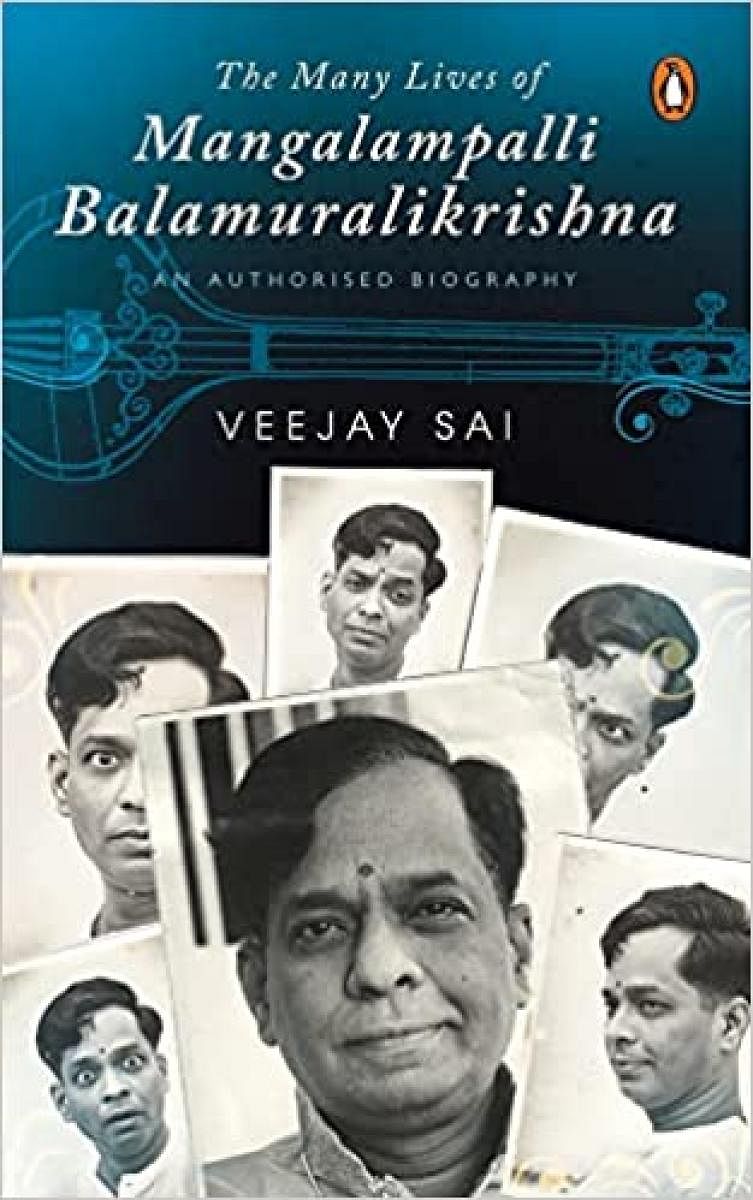

Journalist Veejay Sai’s recent biography titled ‘The Many Lives of Mangalampalli Balamuralikrishna’ contains several such rare details of his life and career that is certain to fascinate music lovers.

“Decades later, a famous Mridangam maestro worked with leather research scientists to ‘discover’ that the aadhara shruti or the base tonal note for the mridangam was rishabham,” Sai quotes Carnatic vocalist Saketaraman.

“Balamuralikrishna had figured this out way back and inculcated it in his kriti ‘Nandeesham’...”

Clash with orthodoxy

Sai’s biography gives us a unique perspective of a musician who clashed rather fiercely with the orthodoxy that faulted him for the way he rejigged the concert structure, innovated on the scales to produce his own ragas and displayed the entire width and breadth of his repertoire to the audience’s appreciation.

Concert goers were used to a strict format but Balamurali introduced an intermission at the stroke of the second hour, baffling some rasikas who asked him if it was a kutcheri or a ‘showbiz’ performance.

“What is wrong?” he retorted, insisting that the interval was for the convenience of the audience, to help them sit through the concert without getting “in and out.” He retorted: “If you (the audience) think that Carnatic music is so sacrosanct, keep it in the confines of the pooja room. Do not bring it on stage.”

Many run-ins

The 1979 raga controversy, which Sai presents in great detail, reveals the extent to which Balamurali incensed the orthodoxy. While he claimed that the attack on him by a group of musicians, most notably Veenai S Balachander and Semmangudi Srinivasa Iyer, was professional jealousy, the row ripped opened the most fundamental aspect of Carnatic music: does a “demarcation” exist between scales and ragas? Can a musician use his imagination to convert a scale into a raga, as claimed by Balamuralikrishna? Attacks on the musician were indeed personal. Balachander called Balamurali’s claims of creating a raga a “gross blasphemous lie”, accusing him of “perpetuating” it to “boost his personal image with an inflated ego.”

His run-ins went beyond the sphere of music. He had a tiff with the former Andhra Pradesh Chief Minister N T Rama Rao, who had abolished the State Sangeet Natak Academy. Balamurali found it humiliating that NTR, being an artiste himself, had done something so drastic without consulting anyone. He vowed not to perform in Andhra Pradesh until NTR remained Chief Minister. In his final years in office, NTR made amends by inviting Balamurali to the state and organised a grand function to honour him.

A pioneer

Sai’s biography reveals how Balamuralikrishna never hesitated to innovate. Though many called jugalbandis a gimmick, he regularly performed on stage with Hindustani stalwarts like Pt Bhimsen Joshi, Pt Jasraj, Vidushi Kishori Amonkar, Pt Hariprasad Chaurasia, Ustad Amjad Ali Khan and Pt Ajoy Chakrabarty, among others. He was also one of the first to sing in films, and as if to annoy the purists further, he sang the film numbers during his concerts! In short, his was a free spirit.

Despite controversies, he will still be remembered for his extraordinarily large body of compositions and concerts, his unique presentations, the ragas he created and, importantly, for showing fellow musicians that innovation is possible in classical music.