The story is simple and as old as time. There is an older woman, and her daughter and there are shifting borders. Out of these three simple entities weaves out a meandering account, dreamlike yet substantial, of homes and homelands. In effect, their story is embedded in the work such that many shades of the lives of all women may be refracted through these waters. It is no coincidence that the women are called Ma and Beti. And that is largely how the book has been written, to lodge under the skin and the thoughts of the reader.

Reading a book in translation despite passable competency in the original language is not kosher.

The only upside is incidental. Via the process, the translator also functions as a curator, somewhat an absurd lover of the book; one who has invested years into trans-creating it in English and therefore worthy of the reader’s trust in a way bestseller lists aren’t.

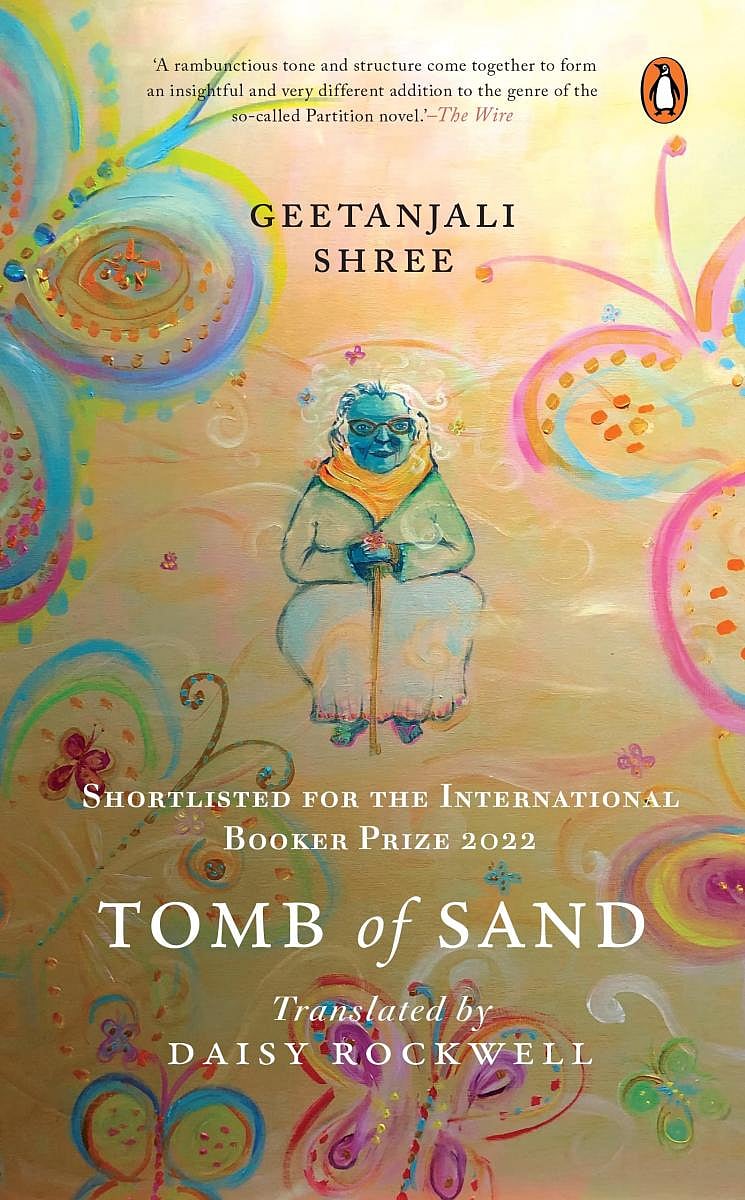

The world seems to agree that translator Daisy Rockwell’s selection and skill are superlative for Hindi author Geetanjali Shree’s Ret Samadhi (2018) as Tomb of Sand has been shortlisted for the International Booker Award 2022. Beti lives alone and is forever jetting away somewhere else as a speaker. Daughter of a civil servant whose anger was his weapon and trademark, she grew up in defiance saying no to everything expected of her. Only her mother understood, the way mothers do.

Beti left home and lived happily despite straitened means until things turned significantly better and her reputation as an expert on gender issues grew. Though the men she dated then are all gone and she lives alone.

Toxic masculinity

After the death of their overbearing father Ma, turns towards her wall and refuses to be alive and well. This disconcerts her son, Bade. In every element, a replica of his father and a poster boy for toxic masculinity, Bade also cares for his mother in a certain woolly-headed, dutiful manner. She seems to have lost the will to live. Even Beti cannot persuade her to sit up or eat. The gift of a walking stick, gold and inlaid with rainbow-coloured butterflies, from the grandson they call Overseas Son changes things. During the course of Bade’s Last Lunch or farewell party, Ma flicks the walking stick to its full length, holds it at 90 degrees and declares she is the Kalpataru.

Shortly after, she goes missing: which sends the family into a spiral of misgivings and blame. On her return, she chooses to leave with Beti.

At Beti’s apartment, freed from all the rules of living in Bade’s official quarters, Ma is alive. KK, the boyfriend who is under wraps so far, decides to introduce himself to Ma; both Bahu and Rosie Bua visit as well. From this scene of domesticity and peace, how do the daughter and mother then land up in hostile Pakistan? More importantly, why? And who is Anwar? That name is heard first when Ma mistakenly tells a police officer that it is her husband’s name.

It is a thing of limitless beauty to find a voice this sure, to read a writer who says so much by indirection. There are layers within that reveal more than the characters, reveal how we are as people and how many of our normative behaviours must be held more open to scrutiny. So much of art, literature and culture flit unselfconsciously through these pages.

A vessel for thoughts

At this point, one loud question silences all others. “Is the book really that good, I mean, to deserve being on the shortlist?” Short answer: “Yes!” This book is a fiction lover’s delight. Whether in the Hindi original, this English version or the French translation, this is unmistakably a gift to all readers. The hallmark of all good writing is that it remains transparent, a vessel for thoughts and ideas, while in itself imperceptible.

What Geetanjali Shree has achieved is mastery of language such that it is amorphous yet indelible. Words have been used as words have rarely before. Objects or customs, the simplest and commonplace, turn into lyrical fragments and the poetry coheres to form an unforgettable epic. Since books are sacred, the editorial errors must be looked at too: the mango is Totapuri, and sattu is roasted gram flour.

This is truly an epic in size and scope except that the characters and their quirks all belong to one family. Perhaps not fully true of a book this exquisite but any 700-page novel is fundamentally bad editing. It drags out and impinges hard upon a reader’s limits.

And most importantly, the experimental writing begins to feel a little bizarre as its canvas is too large to submit to the author’s control. All the other choices made by the author are on point and seem to flout every conventional novel norm. The inventiveness alone sets this novel apart.