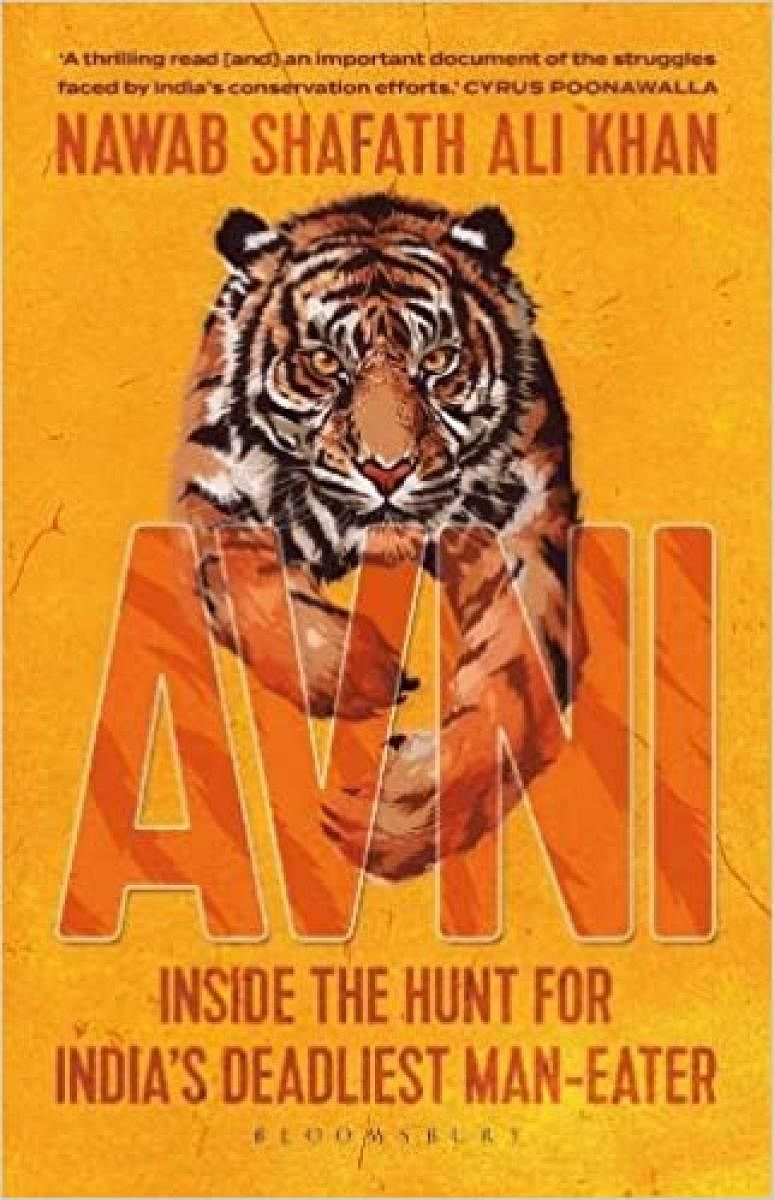

In 2018, a man-eater tigress nicknamed ‘Avni’ was shot dead after officials failed to capture the animal for 2.5 years during which she is said to have killed 13 persons and terrorised parts of Maharashtra’s Yavatmal district. Four years later, the team that took down the animal within 45 days after the job was outsourced by the state Forest Department faces multiple inquiries and court cases.

It is easy to see ‘Avni’, the book, as an exasperated response to the allegations of ‘trigger-happiness’ though such a view may not be completely unfair. The book can also be read as an anthology of stories about rogue tigers, elephants and leopards.

Amid the palpable anger and the thrill of deadly encounters, the book unfolds the sordid state of a system gone awry. First, there is a lack of transparency and accountability in the Forest Department, whose mismanagement of the events is illustrated with horrifying examples. Then there is the plight of people who are increasingly reduced to ‘the number of victims compensated’ without any acknowledgement of the daily trauma.

Man-animal conflict

Take the tragic story of C1, another tiger captured at Brahmapuri after it kills one person. The animal is released unscientifically into a small reserve dominated by six tigers and surrounded by villages. In the next 81 days, C1 kills two villagers and is electrocuted in a farm fence during yet another attempt to capture it. The farmer who had electrified the fence to protect the field from wild boars is arrested.

Such tales, besides highlighting the incompetence of the officials, put in perspective how the system has not only failed the people living on the edge of the forests but also the wildlife.

The author’s full wrath, however, is reserved for Non-Governmental Organisations (NGOs), especially those disconnected from the people facing the outcomes of wrong decisions. The tone of the narration shifts to shrill mode as the book takes on the “politically connected” NGOs lacking a “basic understanding of conservation ethics”.

There is an attempt to discuss the crisis of man-animal conflict — with facts and figures obtained through the Right to Information Act. But by framing the issue as the consequence of an increase in wildlife population rather than the result of loss of natural habitats, the author doesn’t address the elephant in the room.

One can’t help but express disbelief at the author’s conviction that the core forests in India have not been encroached upon because “it simply doesn’t happen, as the boundaries of forests are well protected”. Such assertions fly in the face of thousands of reports, case studies and even court judgments, which have acknowledged the monumental loss caused by state-sanctioned projects, not to mention encroachments.