The Bengal Renaissance is an important part of pre-independent Indian history. Known for kickstarting social, cultural and political transformations within the Hindu society, it also was instrumental in many acquiring the intellectual acumen to confront the colonial powers politically. Notably, many Indian Muslims also participated in the movement.

The Renaissance started in the late 18th century under the leadership of social reformers like Raja Ram Mohan Roy and ended in the early 20th century. Perhaps, Rabindranath Tagore was the last of the luminaries who took an active role in the revival.

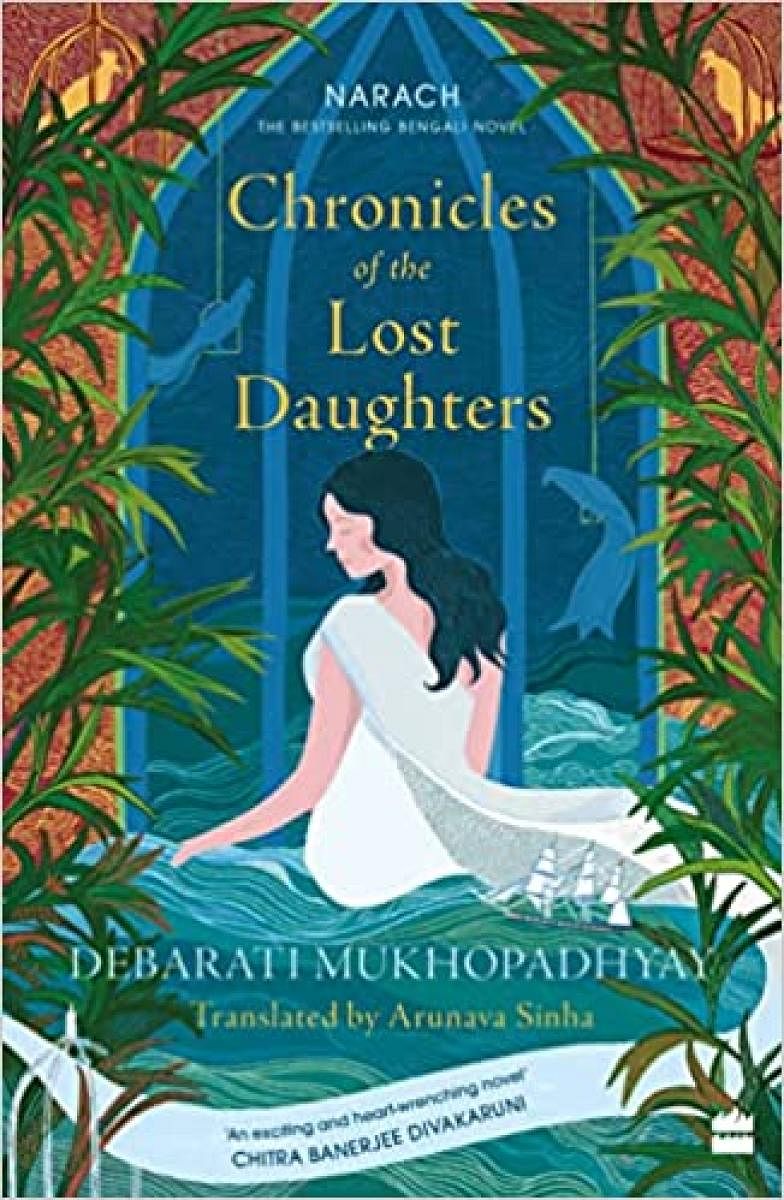

Chronicles of the Lost Daughters depicts a story from this period. The serious debates on the demand for two important Bengal legislations, one, for raising the age of marriage of girls from 10 to 12 called ‘The Age of Consent Act’ and, two, for getting widows remarried called ‘Widow Remarriage Act’, form the important components of this narrative.

Rich characterisation

The backdrop of ‘Chronicles...’ is a Bengali village called Mowshatt. Here, a Brahmin family is devastated by the brutal rape of a beautiful young widow, called Bhubonmoni, by unknown men belonging to an unknown religion of another village. An influential selfish Brahmin of the village wants to make use of this opportunity to satiate his lecherous desires. He suggests that her “impure” body can be “purified” by someone like him cohabiting with her.

Aghast with the intent of the Brahmin, the naive and helpless brother of the raped girl, called Krishnoshundor, along with his raped sister, his wife, his two beautiful daughters and his son flee from the village to find a new job promised by an agent.

Unfortunately, the agent happens to be a cheat who cunningly takes them all to a depot only to make them slaves on a sugarcane plantation in Surinam.

The continuous struggle of this family to disentangle themselves from the clutches of the feudal lords forms the rest of the narrative. The struggle involves losing the girls for good — one dies after forcefully marrying an old man and a sadist sexual assault on her by her own husband, the second one narrowly escapes a similar end and the third one blossoms into a well-informed woman.

There are parallels to this long-drawn struggle of the Krishnosundar family. An idealist young man, Shourendra leaves his home and struggles for existence.

A singer called Chandronath, who comes to the city where his artistic skills are recognised and patronised by the former King of Lucknow, falls in love with a prostitute. After he consummates his affair, he comes to know that the girl is none other than his own sister. He reportedly commits suicide, but there is also a suggestion that he is one of the inmates on a ship, which eventually drowns.

Non-linear narrative

The story is so fast-paced that never once does the reader feel bored. The non-linear narrative has an element of suspense too. All the positive characters in the novel, except the two ‘villains’, “grow” with new awareness drawn from their own experiences into different entities. ‘Villains’ don’t grow, hence one is murdered and the other one dies on his own.

Very few novels achieve this kind of success in characterisation. The fictitious presence of noteworthy Bengalis of the period like Rabindranath Tagore and others as characters in the novel heightens our experience. Though the story is largely about sexual perversions like sadism, sodomy, incest, etc., never has there been any attempt to glorify them. In fact, reading such episodes in the novel makes one feel uneasy and frightened simultaneously.

The novel thus engages its readers genuinely.

The translator has done a wonderful job here ensuring that the novel reads like the original and retains the rich aroma of Bengali culture. It is not just the proper nouns with unique Bengali spellings that attract the readers’ attention, but also some translations of Bengali idioms as well.

Even the unidiomatic usage of English in places (such as the phrase ‘he himself’) does not appear jarring. However, the slightly problematic aspect of the novel is the contrived nature of the narrative. The exploitative agencies are painted in black and the exploited subjects in white.

Perhaps, this seems to be a problem with any politically correct novel. While ideologically one would agree with the assertions made on several issues taken up here, the artistic expressions fail to impress, the reason being that the writer knows how the emotions of her readers work. By either amplifying or quietening the details, the novelist controls the emotions of her readers.