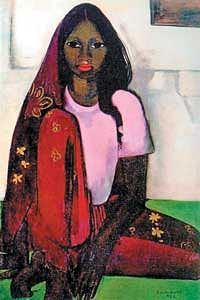

She may have lived to be only 29, but Amrita Sher-Gil’s persona, both as an artist of enduring repute and a woman of colourful escapades, continues to intrigue people several decades after her inexplicable death in 1941. A great many questions about her multi-dimensional life, sometimes dismissed as bohemian, sometimes revered as iconic, have now been answered, thanks to a comprehensive two-volume book titled Amrita Sher-Gil: A Self Portrait in Letters & Writings by her artist-nephew Vivan Sundaram. This long awaited publication (“it took 20 years to complete,” says Sundaram) includes primary material like Amrita’s diary entries as a young child of seven, letters to her family, friends, artist fraternity and admirers as she moved to and fro between Hungary, France, Italy and India, a journey that eventually shaped her both as an artist and an individual.

Born rebel

Born to a Hungarian mother and a Sikh father, Amrita’s initial years were spent studying art in Paris, though she thought she could never be tutored. Her independent streak was visible from a very young age (she was expelled from school for being an atheist), as she later mentions in a published article in The Hindu in 1936: “Although I studied, I have never been taught painting…because I possess in my psychological makeup a peculiarity that resents any outside interference...”

She was not only a prolific painter, the two volumes showing nearly 147 of her works, but also a magician with words. The first volume details her early years in Paris, her interaction with the local artistic community and then her return to India in 1934. Her sharp observation and compassionate world view is evident from the letter in which she chides her mother for being rude to the servants, or when she witnesses a child marriage of which she writes, “Poor little bride, she did look forlorn as she sat in a lonely corner where around the room sat all the Indian ladies clad in gorgeous robes of gold and silver...”

Outspoken, contemptuous and critical of people she disagreed with, barring the famous criminal lawyer and art historian Karl Khandalavala with whom Amrita forged a warm and respectful relationship, Amrita wrote her letters, nearly 260 of them, straight from the heart. Sample this: “You will say that I’m self-opinionated,” she writes when she is only 21, “but I stick to my intolerant ideas and convictions.” Her vulnerability also shines through, being caught between a cold, conventional father and an increasingly deranged mother, when she takes refuge in an artistic vision remarkable for its compassionate world view.

Says Sundaram: “She lived during a period of great political and social turmoil in Paris. It was the age of disease, economic depression and rise of Fascism. When she returned to India, it was this melancholy that got transferred to her canvas when she portrayed the poverty and the sadness of Indian peasantry.” Though Amrita was often criticised for her European sensibilities by Bengal School artists, she continued to choose her subject matter from American Romantic and German Expressionistic films, Tolstoy and Dostoevsky, Chopin and Beethoven. Yet, says Sundararm, “She was an artist representing India in national cultural terms. The tragic melancholy in her earlier works that had a contemporary vocabulary continued to haunt her work even when it gradually became more detached and de-romanticised, such as in paintings of women in Indian feudal setup.”

Ironically, however, while Amrita’s body of work largely involve landscapes, portraits and myriad scenes from village life, she is mostly remembered for her sensuous female nudes, the earliest such works from the time when as a 10-year-old she returned from Florence to “draw watercolours of seemingly sinful arts — of nude women.” Grimaces Sundaram, “Nude studies were a miniscule part of her oeuvre. She made only one nude of her cousin Sumair when she was in India. She was drawn towards human forms and landscapes and the synergy between the two.”

While the jury will always be out on whether Amrita received any substantial success as an artist during her own lifetime, she herself had a very decisive and dismissive view of Indian art that existed then. In one of her letters to RC Tandan, she describes Indian art as “putrid specimens of fifth-rate western academic painting,” and has similar disparaging remarks to make about Nawab Salar Jung of Hyderabad who had “millions of rupees worth of junk.” She is said to have retorted to him: “How on earth anybody with any taste could buy Leightons, Bouguereaus & Watts, when there were Cezannes, Van Goghs and Gauguins in the market,” as a result of which she thinks he did not buy any of her “cubist paintings”, leaving her to wonder how she might have fared “if I were a sycophant.”

“She was sharply critical of those she didn’t approve of her but very generous with her compliments as well,” says Sundaram, recalling a letter to Karl Khandalavala in which she defends Tagore as an artist “since he is self taught.” She also found Ajanta inspirational: “When it’s good, I don’t think I have ever seen anything that can equal it.” In an article in The Indian Ladies' Magazine, she writes that she wants “to paint those silent images of infinite submission and patience; to depict their angular brown bodies strangely beautiful in their ugliness…” Travelling across India, in a letter to her parents, she observes that “a fresco from Ajanta… is worth more than the whole Renaissance!”

Her adult life in India, portrayed through her published articles and letters in the second volume of the book, is also best remembered for her bohemian lifestyle and endless liaisons with men from different walks of life, all happening while she continued to profess her commitment to marry her first cousin Victor Egan, a decision that was to later estrange her from her family completely. One of her most speculated relationships was the strong attraction she had with Nehru and vice versa. In a letter dated November 6, 1937, she writes, “I should like to have known you better. I am always attracted to people who are integral enough to be inconsistent without discordancy — and who don’t trail viscous threads of regret behind them.” But she also rebukes him for not being interested in her paintings: “You looked at my pictures without seeing them,” she wrote to him.

Always in love

Promiscuity does not seem to have been alien to the family — her mother’s affair with sculptor Giulio Cesare Pasquinelli was rather well-known and so was her attachment to poet Iqbal — but as Sundaram says, “she was unabashed about the uselessness of giving too much importance to bodily desires. She was eager to know other people’s minds, even if it meant reaching there through their bodies.” To art critic Karl Khandalavala, Amrita wrote: “I am always in love, but fortunately for me and unfortunately for the party concerned, I fall out of love or rather fall in love with someone else before any damage can be done!”

Her mother, in fact, seemed to have shaped Amrita in more ways than one. She was ambitious and dominating who pushed Amrita to achieve more and more. Most of Amrita’s letters to her mother claim that “I am working real hard” while showing a daughterly concern for her mother’s failing nerves and deteriorating financial condition of the family. Amrita’s relationship with her father appears more philosophical while she shares an easy and warm sisterly banter with Indira (Vivan’s mother) to whom she complains of “taking all her furs and coats away to India while she ‘freezes in Paris’.”

While Sundaram hints that Amrita’s struggle as an artist would have been different if the family had settled in Lahore instead of Shimla on their return to India (“Lahore had a far more stimulating cultural and political environment compared to the colonial-elitist Shimla,” he says), Amrita’s search for a home continued even after she left for Hungary in June 1938 to marry Egan despite strong opposition from her parents. On their return to India, while her canvas blossoms with studies of woman folk and their cloistered existence, her personal life takes a turn for the worse about which she laments in a letter to her father about, “Mummy in her usual hostile and prejudiced manner,” accuses her husband of “laziness, irresponsibility and desire for shirking work,” as a result of which “old wounds in our hearts are still festering…”

She writes to her sister Indira in March 1941, “I have passed through a nervous crisis and am still far from being over it. Feeling impotent, dissatisfied, irritable and unlike you, not even able to weep…”

When Amrita died in 1941 in Lahore, with speculation about the cause as much variegated as the short life she lived, just on the eve of a major exhibition, she left behind a story that can be told and retold in many ways.