One of the most admired artists of his time, Bikash Bhattacharjee breathed his last on December 18, 2006, aged 66.

It was in the 1970s that the young Bengali painter had taken the country’s art scene by storm. His participation in the First Triennale-India (Delhi/1968), followed by solo exhibitions in Bombay and Delhi in 1970, had attracted widespread attention.

In the following decades, he was to become an integral part of the Bengal art movement. Along with masters like Somnath Hore, Ganesh Pyne, Jogen Chowdhury and Sunil Das, he represented the cream of Bengal modernism. His works were exhibited across the country and commanded high prices.

“Bikash’s skill was superior to his contemporaries,” recalls Amitabh Sengupta, an eminent artist. “He developed an effective context by employing the touching narrative of middle-class life.”

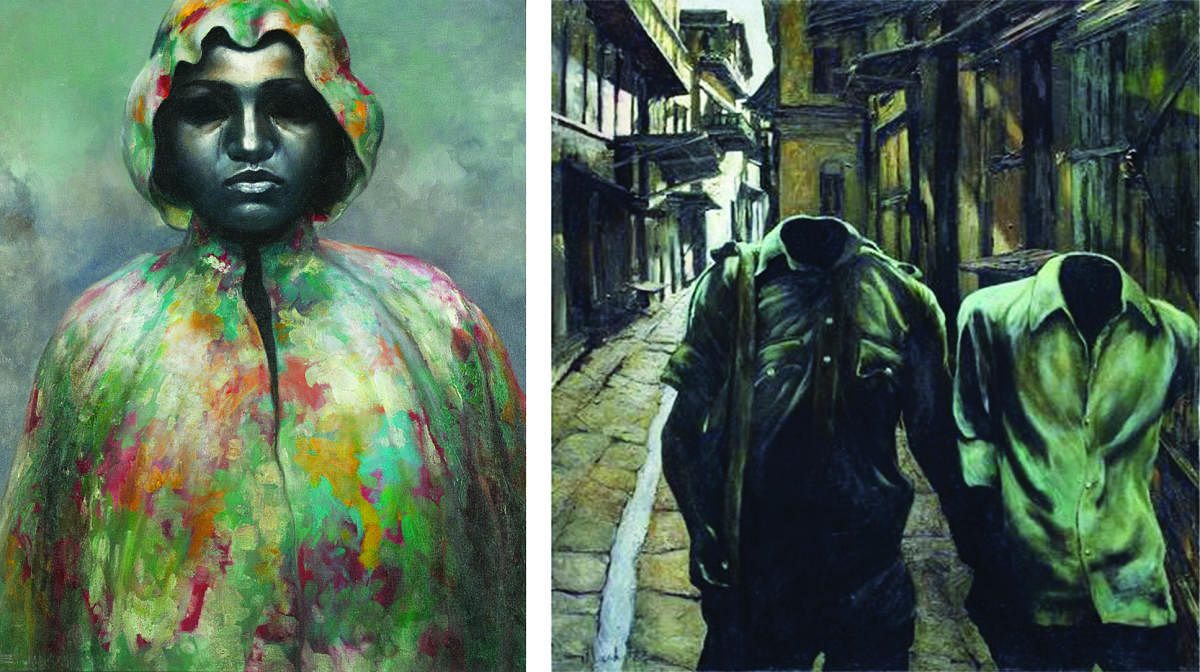

Bikash did not paint pretty pictures. His richly coloured and immaculately composed images of a decaying and chaotic city were, in fact, emblems of gloom, doom and tragedy. Infused with palpable tension, disquiet and unease, his paintings were often touched with shades of menace, creepiness and cynicism. What perhaps distinguished his work most from others was the penetrating ‘surreal’ accent given to mundane objects, everyday happenings and common people on the street. “Each scene is painted with a loving attention to light, texture and detail,” observes art critic Jaya Appaswamy. “The compositions are very stable, the unreal is cradled in the real, the pictures are the starting point of questions and reveries that linger in the mind.”

Oh! Calcutta!

The primary inspiration for Bikash’s art evidently came from Calcutta. He was born and brought up in the ‘city of joy’, which ironically personified trauma, struggle, death and decadence for him in his growing-up years. Having lost his father when he was just six, he had witnessed from close quarters, how his mother, a young widow, had struggled to raise her two sons under excruciatingly trying circumstances. Personal struggles and tribulations apart, Bikash also came face-to-face with the many socio-cultural and political facets of the city — all of which had a bearing on sharpening his artistic sensibilities.

The many moods, attitudes and physical structures of the city offered themselves as perfect models for his striking if tragic canvas. With its anxiety-stricken populace, violence-marred politics and spiteful social environment, Bikash perceived the city to be always on the edge. Calcutta’s labyrinthine lanes, crumbling buildings and red-light areas came to occupy haunting and critical positions in his images.

“I see myself as a sort of painter-journalist, using paint and canvas as a photo-journalist might use his camera,” he once said. “What I have to say is right there on the canvas.” He believed that an artistic work not only embodied an identifiable reality, but also told an evocative story. He also confessed that he painted because he could not do anything else.

Dolls and Durga

In a career spanning over 40 years, Bikash produced several breathtaking and forceful series of paintings.

Perhaps the most remembered one is the Dolls series, in which he replaced the human figure with a baby doll and positioned it in several defining and disturbing contexts of a terror-struck city.

“What was remarkable about these paintings was their insidious disquiet,” observed a critic. “There was no (direct) reference to violence. But to see a doll rummaging in a chest of drawers, high above the ground, its chubby legs hanging dangerously; or to see it emerge, warily, from behind a blind, rundown wall, summons the kind of precarious dread and bewildered vulnerability people felt at the time.”

Bikash’s Durga series was equally powerful in its portrayal of a common woman seemingly trapped in a frenzied universe. Bikash, who seemed to have consciously evaded the trappings of the orthodox Bengal school, did not shy away from multiple influences of the West, thereby earning the nickname of Bicasso. Masters like Francisco Goya, Salvador Dali, René Magritte, Francis Bacon and Max Ernst could be seen sneaking into his rich and complex images. “Bikash is a painter of our time,” eulogised artist M F Husain, “whose browns are burnt, like in a Rembrandt.”

While his talent and abilities were generally acknowledged, Bikash also had his detractors.

“Bhattacharjee’s illusionism is disappointing,” wrote art critic Richard Bartholomew in 1972. Two years later, the same critic felt that “the element of surprise in Bhattacharjee’s surreal work is wearing thin.”

Such comments and remarks notwithstanding, Bikash’s reputation grew steadily through the final decades of the last century. Many awards came his way, including the Banga Ratna (1987) and Padma Shri (1988).

It was in 2000 that the versatile artist suffered a cerebral attack, which sadly snatched him away from his beloved canvas. After spending the last six years of his life on a wheel chair, the painter who once dominated the Indian art scene, breathed his last.