The Japanese had imprisoned some 75,000 commonwealth soldiers in war camps on the swampy island of Singapore in the spring of 1942. One young Indian prisoner with a Bengaluru connection was determined to escape.

Second Lieutenant Markandan “Mark” Pillai of the Bombay Sappers and Miners, a native of Tirunelveli in Tamil Nadu and a graduate of St Joseph’s College in Bengaluru, had joined the army in 1938. Within months, World War II broke out.

In four weeks, starting in December 1941, the relentless but numerically inferior Japanese Imperial forces had driven the Allied divisions 1,000 km down the Malayan peninsula and pinned them down at Singapore, their backs to the sea.

The island was already in shambles by the time Pillai and the Allied forces took up positions on the last day of January 1942. The first Japanese air attack had already taken place at 4.15 am on Monday, December 8, 1941 (hours after the Japanese attack on Pearl Harbour).

The whistling of falling bombs and the explosions had pierced the slumber of the population. Those who rushed out of their homes could see aeroplanes droning high above, black plumes of rising smoke streaming up from the eastern part of the city.

On a small hillock, an elderly English woman ran into her bungalow. Snatching her telephone, she yelled to the police: “There’s an air raid going on!” That very moment, another explosion near her window hurled glass everywhere. The British voice on the other end came back: “Don’t worry. It is just our boys up there. They’re just having a bit of practice.”

But a rude awakening was in store for Singapore and the British top brass, who had comforted themselves that the “Japanese have such weak eyes that they can hardly see straight, much less shoot straight.”

By February 15, it was all over. The hubris of the Allies had delivered the gleaming jewel of Singapore at the feet of the Japanese army. Pillai’s unit, No 45 Army Troops Company, was in dismal shape: four of eight officers, and 97 of 240 jawans were dead or mortally wounded. Pillai and thousands of others were packed into 13 prisoner of war camps on the humid, mosquito-infested island.

Food was becoming scarce (camp rations comprised two chapatis a day and a cup of black tea with no sugar). Brutal punishments such as beheadings were not uncommon. Already, the Japanese had machine-gunned thousands of Singapore’s Chinese residents on the beaches. The army prisoners faced the prospect of slow death, following their transfer as slave labourers to distant Thailand, Borneo and Manchuria.

Pillai’s determination to escape became acute on February 16. “I felt a slight ray of hope and the strength of resolution,” he would write in a diary preserved to this day by his family in Bengaluru. “I decided to escape, come what may.”

He thought he would swim to Sumatra but would the sharks let him complete the journey? Then, a strategy crystallised: he would pose as a civilian with a fellow south Indian living in Singapore. He had befriended K Radhakrishnan, and together they decided to walk back to India if necessary. His commanding officer, Major Ronald Dinwoodie, was unhelpful. He pointed out that the Bombay Sappers’ depot at Kirkee was 6,100 km away. But Pillai’s resolve was cemented when a jawan serendipitously gave him two books: ‘On the Run’, and ‘Phillips International Atlas for Naval Officers’.

Together with Radhakrishnan (35), a lecturer at the Singapore Trade School and Capt Natarajan (39), an army doctor, Pillai hoped to travel via Thailand and Burma to reach the India border, a daunting 3,300 km away. He studied the atlas in detail, committing parts of it to memory.

Radhakrishnan, having sent his wife and children to India before the war broke out, had drummed up 600 dollars (today’s equivalent 10,300 dollars) by selling his possessions. Natarajan and Pillai had 100 dollars between them, and a bagful of anti-malarial pills which they hoped to barter along the way.

Finally, after 11 weeks as prisoners of war, on May 6, Pillai and Natarajan slipped out of their camp at Bidadari and linked up with Radhakrishnan to make their bid for freedom. Pillai had been assigned to attend a lecture by Capt Mohan Singh of the fledgling Indian National Army (INA) the following day. He had to be well away from the island before his absence was discovered.

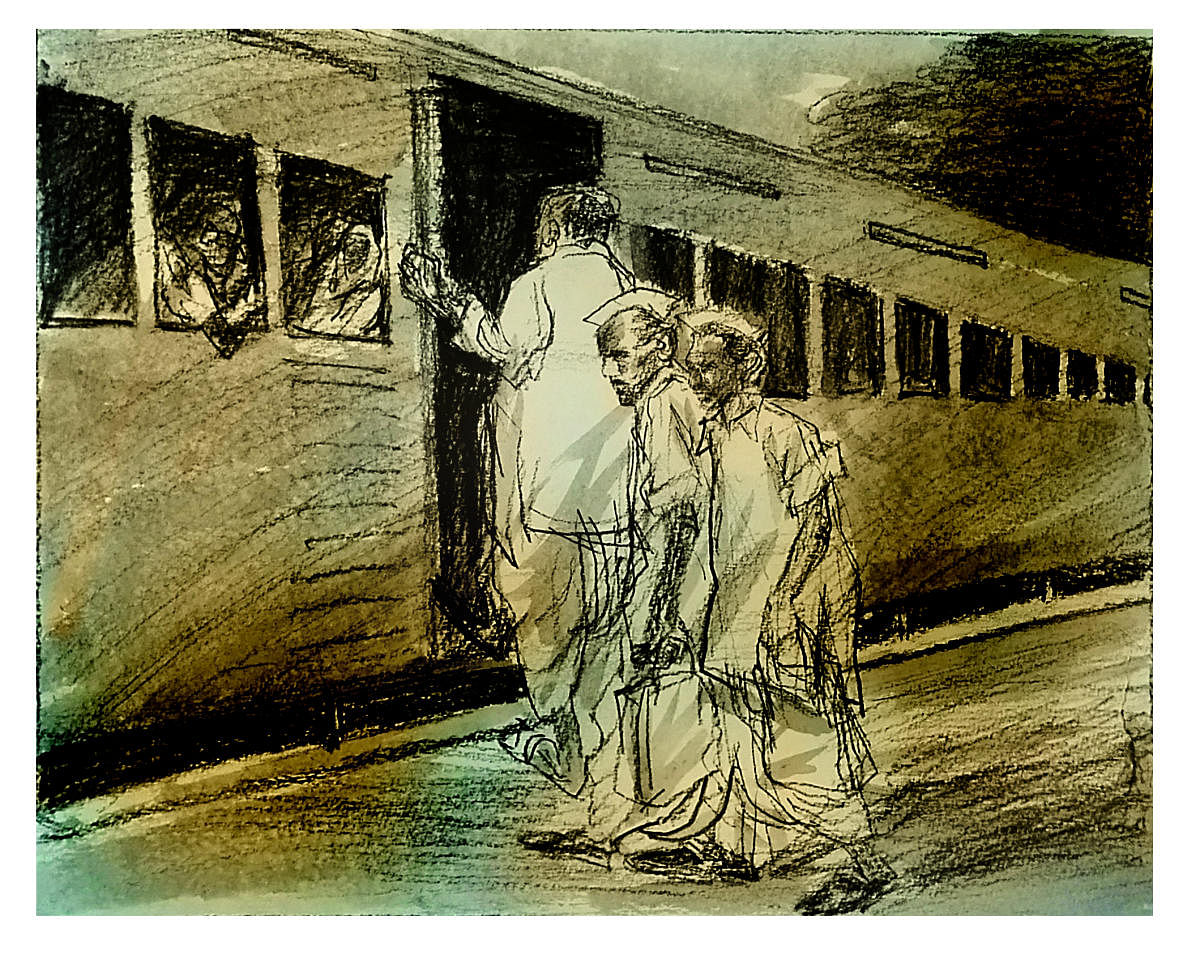

Wearing dhotis, long shirts and Gandhi caps, the three boarded a train with tickets to Penang in Malaya (now Malaysia), posing as onion and potato traders. The large diaspora of civilian south Indians in the region served as camouflage. There was no turning back now.

Pillai’s son, Sampath, later put their escape in context: “There were 2,200 escape attempts by prisoners of war during World War II. Only about 10% were successful.”

But while getting out of the camps was one matter, getting home was another.

According to the Imperial War Museum in the United Kingdom, of 1.7 lakh British and Commonwealth prisoners of war in German camps, less than 1% made successful “home runs”, reaching Allied territory. The death rate of prisoners of war in Japanese camps was 27%. In German camps, the rate was 4%.

To stay in Singapore was to court disaster. Insanity had already gripped the camps. An Indian sergeant was beaten to death over suspicion that he was distributing food unevenly. One of Pillai’s men kept asking for an official transfer back to India, unable to understand that he was a prisoner. Cases of malaria, dysentery and vitamin deficiency were rife.

Among those who did not escape, 12,000 died building 420 km of the railway from Siam to Burma in a climate where beriberi, cholera and malaria ran rife, and Japanese cruelty raged.

A journey through hell and then to freedom

To cover 3,300 km, they travelled on a goods train, hopped on to a truck, then took a boat, and finally trekking across desolate mountains

Three Indians escaped Japanese-held Singapore in 1942 during World War II. This is how the action panned out:

For Second Lieutenant Mark Pillai, Capt Natarajan, army doctor, and K Radhakrishnan, lecturer at the Singapore Trade School, the prospect of death during a hard, 3,300-km journey back to India was preferable to life under Japanese occupation.

They got on a goods train to Siam (now Thailand), and the initial leg was uneventful. When they changed trains at Padang Besar to go to Hat Yai in Siam, they discovered to their mortification that their companions on flat cargo trucks were Japanese soldiers.

Siamese immigration officials discovered that the group did not have visas. The three were thrown into a local jail. But an influential local Tamil businessman had noticed their plight. He offered to help but sought 450 of the 700 dollars they had on them. This bought them a permit allowing them to stay for 30 days in Siam. They had spent a lot of their money within seven days of their escape from Singapore. And they had to leave within 30 days. But how?

China was 500 km to the north. But anti-Indian sentiment was rife north of Bangkok. The group decided to cut through Burma in the west. Southern Burma was dominated by thick jungles, replete with dangerous animals and poisonous snakes. Better to brave hostile animals than people, they reasoned.

For weeks, the group witnessed scenes of horror: travellers murdered by bandits, bodies scattered across roads, starvation, babies flung up by Japanese troops and bayonetted in mid-air, bombed-out landscapes, and the dead and the desperate vying for space in a tropical hellhole. Radhakrishnan was disgusted by the “barbaric” Japanese, and would later complain that he was “appalled by the ignorance of Japanese methods… in India.”

Their bus stopped near the border where a stretch of water, half a mile wide, separated the two nations. The “thought of swimming across was almost irresistible,” Pillai wrote in the diary, adding that both he and Natarajan were good swimmers. Then came a blow. Radhakrishnan could not swim at all.

As the escapees took a boat to Victoria Point in Burma, they met a group of Australian and Dutch prisoners of war being used as slave labourers. It was a stark reminder of a fate they would potentially share if they were uncovered.

By the time they reached Moulmein, on the road to Rangoon, on June 10, they were out of money. They sold the last of their possessions: a diamond ring and a watch for just Rs 11 to an Indian banker, whom Pillai described as being “utterly lacking in sympathy and compassion to his countrymen in dire straits.”

By the time the group, bedraggled and hungry, stumbled into the Burmese town of Prome, 170 miles north of Rangoon, it was the last week of June and sweltering. They had little money but now the Indian frontier was only a few hundred kms away, tantalisingly close for the three men who had travelled over a thousand.

They decided to cut west towards the sea, 100 km away, to enter the Arakan peninsula on the border with India (now Bangladesh). Then came more bad news: the Arakan was the scene of heavy fighting between Japanese and Indo-British forces. Civilians were fleeing.

There was no alternative but to go further north and get into Assam. At this point, Natarajan announced that he would remain in Prome. A later intelligence document suggests that Pillai and Radhakrishnan were privately relieved. Over the past few weeks, the doctor had become increasingly loose-tongued. His indiscretions had, at least on one occasion, forced them to flee a safe house. They thought Natarajan had INA sympathies, and could ruin their plans. Leaving the captain behind, the two men took a small boat up the river Irrawaddy, passing the Yenangyaung oil fields, which had witnessed savage fighting in mid-February.

The Indo-British-Burmese troops, under Maj Gen James Bruce Scott, were almost trapped. In the ensuing rush to escape, many of the wounded were left behind, only to be butchered by the Japanese.

The border beckoned. But a Japanese soldier commandeered Pillai’s boat, leaving the two men again in the lurch. They continued, inveigling transport by road or by river when they could. The Japanese and their own hunger had failed to deter them, but two tributaries of the Chindwin river brought them to a halt because Radhakrishnan could not swim.

Pillai had to trick his companion into the water and haul him across by rope. Soon, they found themselves trekking across desolate, jungle-clad mountains. They reached the Burmese frontier town of Kalewa. It was almost August. They crossed the border and were in India.

An Indian Army patrol, led by a grizzled Sikh sergeant, appeared. Pillai and Radhakrishnan jumped for joy. But then the sergeant and his men turned their guns on them. “I have seen a lot of people like you trying to sneak into India,” the sergeant said, with a sneer. “I have come here to kill the Japanese, not to take prisoners.” Clearly, they had been mistaken for fifth columnists sent by the Japanese.

Pillai started running. A machine gun sprayed the stone around his feet. Anger replaced fear. Pillai stopped and whirled around, hurling fluent army obscenities in Hindi. The sergeant was convinced that this half-starved creature was indeed an army officer. He ordered his men to lower their weapons. The ordeal was over. It was August 2, 1942. Ninety days had passed since the two had escaped Singapore.

Questions began about Radhakrishnan. Because entry into Allied lines was restricted, Pillai gave Radhakrishna the fictional rank of Lieutenant in the Singapore Volunteers. No such army unit existed!

Things moved at dizzying speed. The two men were soon at the Allied General Headquarters in Delhi, sharing the honour of being the first Allied PoWs to return from Singapore. Anxious officers questioned the pair for days to gather what was happening in the lost territories.

Pillai was put in for an immediate Military Cross, as was “Lt” Radhakrishnan, even though as a civilian he did not qualify for this military decoration. When the army discovered his status, they simply commissioned him as an officer into the Corps of Engineers.

The long trek, however, had hollowed out the two men. Pillai weighed less than 40 kgs (29 kgs less than before). Radhakrishnan fared worse. He never recovered. He died in 1945 in his hometown of Guntur, Andhra Pradesh.

Natarajan never returned to India. He married a Burmese woman and died in Prome in 1951. Pillai went on to become an instructor in the Jungle Warfare School in Shivamogga. He retired from the army in 1961 as a Brigadier. He died in Kodaikanal in 1988.

What had prompted Pillai to attempt such an escape? Certainly, a longing for home and stories of heroism he had read in books, he acknowledged. But there was also a willingness to prove to himself that even a slight, “rice-eating south Indian” could take on impossible odds to fight another day.

Watch the latest DH Videos here: