This year marked the demise of two revered artists who, in their own unique ways, contributed to the genre of abstraction. Both lived long enough to cross their 100th birthdays, had exceptionally extended artistic careers, worked almost till the very last, and left an indelible mark through their art.

Widely regarded as one of the most influential French painters, Pierre Soulages passed away at a hospital in Nimes, France on 26 October 2022, aged 102. "Soulages was able to reinvent black by revealing the light," reminisced French President Emmanuel Macron in his tribute on Twitter. "Beyond the dark, his works are vivid metaphors from which each of us draws hope."

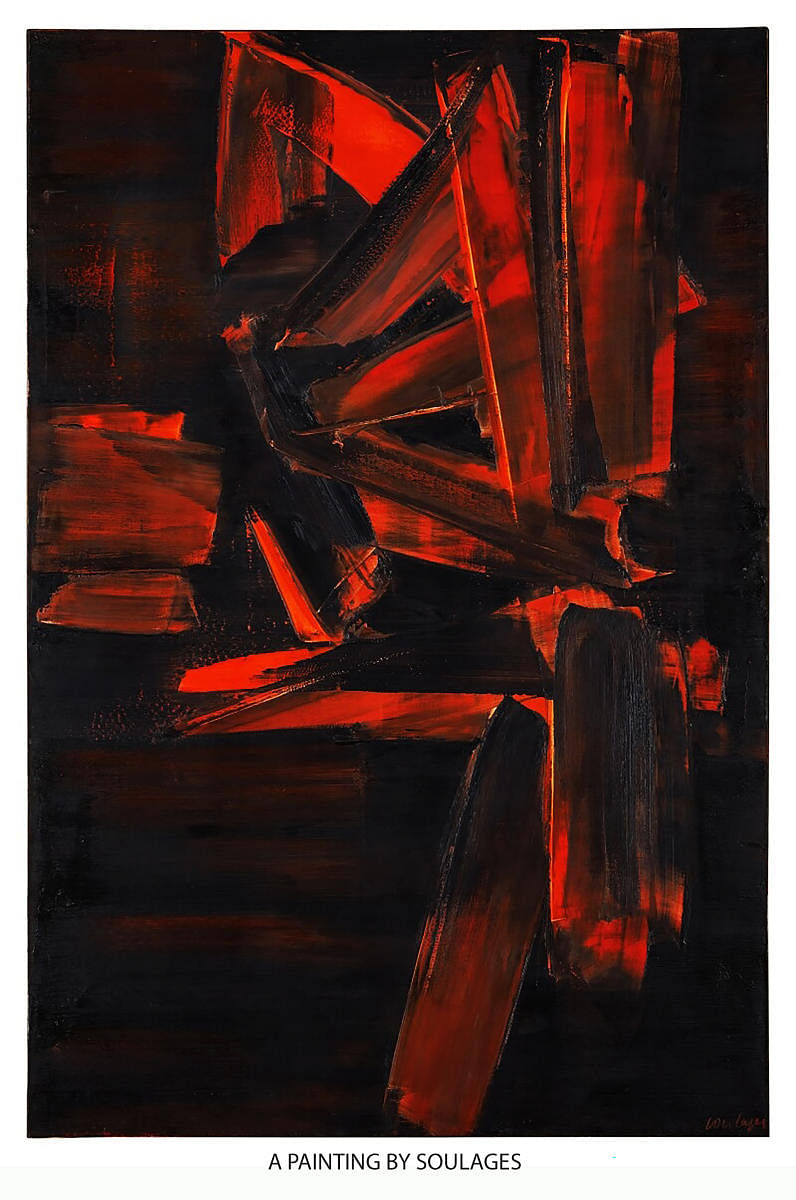

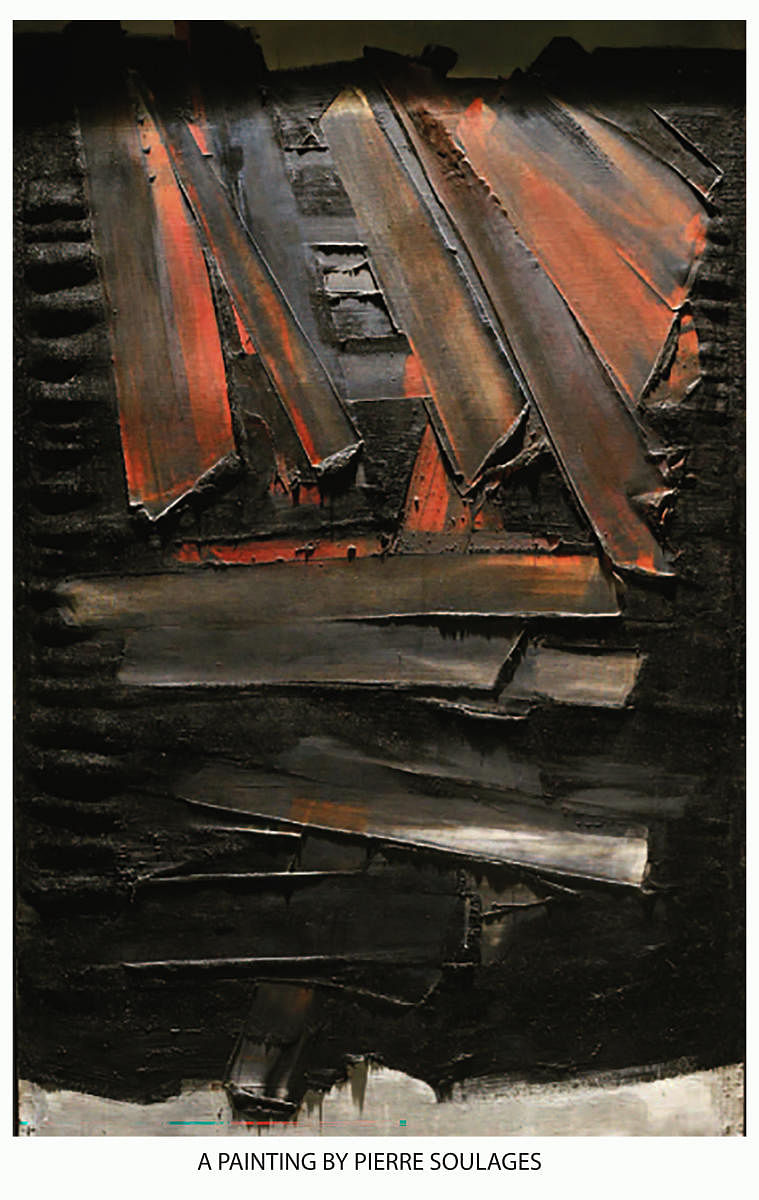

In a career spanning seven decades, Soulages, 'the master of noir', reportedly produced more than 1,700 canvasses working almost exclusively in black. Employing specially equipped brushes, knives, and other implements he created intricate patterns and textures on canvases smeared with thick black paint. Critics were amazed at the manner in which he could bring about hundreds of variations of paintings in a single colour. “Black is a very active colour,” explained Soulages. “There are nuances between the blacks… I paint with black but I’m working with light. I’m really working with the light more than with the paint.”

The ‘painter of black and light’ who was born on Christmas Eve, 1919, confessed that his primary inspiration came from studying prehistoric cave paintings. “It’s fascinating to think that as soon as man came into existence, he started painting… Prehistoric art came to move me much more than Greek art. Greek art has beautiful women and handsome men, but I don’t care.” He believed that painting allows us to live in a more interesting way than we live our everyday lives. “Painting isn’t just pretty or pleasant; it is something that helps you to stand alone and face yourself. For me, it’s important to experience this aesthetic shock, which sets in motion our imagination, our emotions, our feelings, and our thoughts. That’s the purpose of a painting and of art in general… If a painting doesn’t offer a way to dream and create emotions, then it’s not worth it.” He also loathed the categorisation of art in any manner. “Well, all those terms—abstract, nonfigurative, et cetera—they’re just words, they’re labels, and labels are meant to be destroyed.”

Soulages was known to be a perfectionist who did not think twice about burning the paintings he did not like. His 100th birthday was marked by a special three-month exhibition at the Musée du Louvre, Paris. With that he became only the third contemporary artist in history to receive a solo exhibition at the Louvre, the other two being Pablo Picasso and Marc Chagall. In 2001, he became the first living painter ever to be exhibited at the Hermitage Museum in Saint Petersburg, Russia.

As France’s most celebrated artist, Soulages had his works widely exhibited and eagerly collected. In November 2019, one of his black canvasses painted in 1960 sold at auction in Paris for €9.6m ($10.7m), making him the country’s most expensive artist.

In awe of the straight line

While Soulages pursued the black colour throughout his life, the Cuban-born American abstract painter Carmen Herrera (who passed away on 12 February 2022, aged 106) found inspiration in the beauty of a simple straight line. “I believe that I will always be in awe of the straight line. Its beauty is what keeps me painting.”

Fame and market success came very late for Herrara. While her visionary geometric abstractions became highly fashionable for collectors later, the New York-based artist ironically gained recognition only after she sold her first painting in 2004 at the age of 89. Till then she had worked relentlessly but in relative obscurity.

Born in Cuba in 1915, Herrera studied architecture at the Universidad de la Habana, which probably fuelled her obsession with the straight line. Abandoning her studies, she moved to New York in 1939 after her marriage to Jesse Loewenthal, an American visiting Cuba. Between 1948 and 1953, the couple lived in post-war Paris where Jesse taught English and Herrera refined her painting style. She came in contact with many artists and writers including Sartre, Matisse and Picasso.

Over time, Herrera became increasingly minimalist in her work. Her paintings acquired a lyrical yet dynamic character because of the bold colours and sharply defined shapes and geometry. But she could not find buyers for her work. And her reasoning was simple: she was a woman in what was essentially a man’s art market. “Men were better than me at knowing how to play the system, what to do, and when. They figured out the gallery system, the collector system, the museum system, and I wasn’t that kind of personality.”

Thanks to the unstinted support and encouragement of her husband, Herrera continued her practice and developed images of high visual intensity. When she finally received popular and critical attention after turning 93, her fortunes changed dramatically. Private collectors flocked to buy her works; shows were mounted in the US as well as in Europe, and adulatory reports flashed across frequently in the press. Consequently, the value of her paintings also soared.

Herrera took it all in her stride. “Being ignored is a form of freedom,” Herrera wrote. “I felt liberated from having to constantly please anyone… So, I just worked and waited. And at the end of my life, I’m getting a lot of recognition, to my amazement and my pleasure, actually.”

In her final years, Herrera became arthritic and wheelchair-bound. That did not stop her from developing ideas for new pieces and bringing them to fruition with the help of a long-term assistant. Carmen’s only regret was that her husband (who passed away in 2000, aged 98) did not live to see her success.