Minneapolis in the United States and Santhankulam in Tamil Nadu, India, are separated by 14,000 kilometres. Both hit headlines in recent times over widely publicised incidents of police torture.

This brings to mind what happened in Abu Ghraib in 2003. Located about 20 miles from Baghdad, the US military prison held several thousands of (mostly) civilians picked up from streets and homes and treated them like criminals. Reports of systematic and illegal abuse of detainees by the captors emerged in the spring of 2004. Stark images of humiliation, torture and sexual cruelty went viral on the internet. They showed naked men in shackles piled up as pyramids; hooded prisoners connected to electrical cables; vicious police dogs growling on inmates’ faces and so on. Counterbalancing such sordid images were the grinning and mocking faces of American soldiers and officers who took photographs of their despicable deeds.

A global outrage

The Abu Ghraib images caused a worldwide scandal. Like others, artists across the globe were outraged and gave vent to their feelings through artworks. “I was full of rage, when I started to work, at the monstrosity and the hypocrisy of the situation,” said Latin America’s best-known living artist Fernando Botero (born 1932, Medellin, Columbia). “The shock I felt, as a human being and as an artist, compelled me to leave a testimony against the horror.”

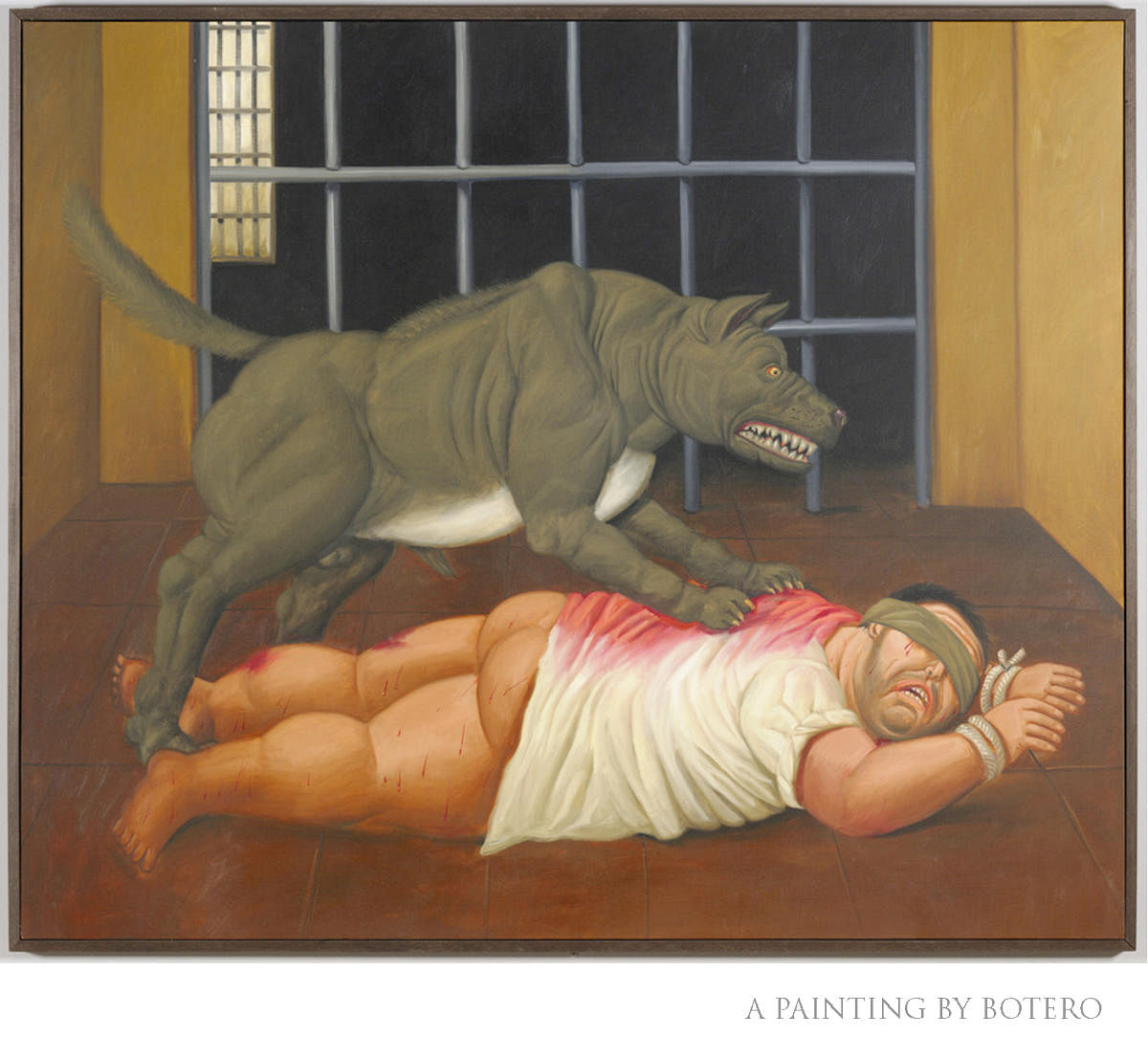

Botero’s series of 80 paintings and sketches in oils, pencil and charcoal portrayed naked prisoners dangling from ropes, attacked by dogs and beaten by guards. “These works are a result of the indignation that the violations in Iraq produced in me and the rest of the world.”

Interestingly, Botero’s paintings and sketches of prison abuse were conceived not from photographs or specific acts of torture, but rather from his reading of news reports, particularly the explosive article of Seymour M Hersh published in The New Yorker on May 10, 2004. The Columbian artist spent 14 months drawing and painting, working nearly nonstop on pieces that have been compared to those done by Francisco Goya and Pablo Picasso.

Not for sale

Many of the paintings were life-size, brightly coloured and carried his characteristic bloated figures. Botero declared that the paintings were not for sale. “It is immoral to make profits from human suffering.”

The works were exhibited in different venues, including Rome, Milan, Stuttgart (Germany), and Vigo (Spain). While they garnered considerable critical acclaim in Europe, no US museum agreed to display the works. Finally, when the paintings were exhibited at the Center for Latin American Studies, the University of California, Berkeley, in early 2007, it reportedly attracted as many as 15,000 viewers over a period of seven weeks. In 2009, Botero donated much of the series to the Berkeley Art Museum.

In a later interview, Botero clarified that he would not respond each time there was injustice in the world. “I believe that art has some responsibility in front of some facts, but the most important responsibility is with art itself. You can show torture in your work, but what you do has to be, first of all, art. I will not be the eternal ‘cronista’ (chronicler) of the dramas of humanity.”

Beauty and horror

American painter and printmaker Susan Crile too was disturbed by the Abu Ghraib photographs and felt she had to do “something”. Using the images as the baseline, she worked on a series of drawings rendered in a sombre palette on dark sheets of paper using pastel, charcoal and chalk. “Beneath it all, my work is about humanity,” she explained. “My work is also about torture, what man does to man, what it is to experience extreme pain. It is about how we respond to injustice; about understanding what it is to destroy the humanity of others, to create extreme pain in another person. Whether they’ve done wrong or have not done wrong, nothing justifies torture.”

Crile saw her work as inhabiting the space between beauty and horror. “In the case of torture, perhaps the pendulum doesn’t swing all the way to beauty, but it does something close to that in representing human pain, as seen through the suffering of the body … In the history of culture and the history of art, horror and ugliness, specifically in religious art, have often been fused with the aesthetic.”

Crile’s 23-odd works were exhibited at the Hunter College, New York, during September-October 2006. “Ms Crile’s sincere desire to elicit empathy for her subjects is laudable,” observed the New York Times critic, “but, none of her drawings have the gut-wrenching impact of the shameful photos themselves.”

A political statement

One of the most significant and controversial sculptors of America, Richard Serra, is essentially known for his exceptionally large metal works. He too could not hide his indignation when reports from Iraq filtered in. “The whole Abu Ghraib atrocity got me very angry,” he recalled. “I went to some marches, but I wanted to do more than that.” Serra’s act of protest came out in the form of a poster against the Bush administration and the abuses at Abu Ghraib. The stark black-and-white picture showed a hooded prisoner — an apparent reference to the Abu Ghraib scandal.

“My concern wasn’t aesthetic at all. My concern was completely political… The Stop Bush image was made as a political poster that anyone could download. And I went on to distribute it — we made a couple hundred thousand for both the conventions and for marches and rallies. And then I went on, actually, to make a signboard on 10th Avenue.”