All the goings-on in Anita Nair’s Eating Wasps is situated in a riverside resort in Kerala, and the reader will find the state arches over the story with its topography in all shades of green, its pazham poris/ idiyappams/ ela adas, its people with and without pathras, the last loosely translated as pomp and circumstance.

The book loosely whirls a set of related and not-immediately-related stories, all of them dealing with what women want, what women yearn for, what women fear, and what women seek. One of the common factors between the women is the River Nila that runs near the resort, looked at with delight, equanimity and despair at different times by different women. The book has a great hook in its opening line: “On the day I killed myself, it was clear and bright.” We are thus introduced to Sreelakshmi, award-winning author and high school zoology teacher who killed herself a long time ago. Further intriguing is what Sreelakshmi goes on to say: “I had not just killed myself, I had dug my own grave.”

Piquantly enough, it is not Sreelakshmi’s ghost (the other common factor) who is the narrator of Eating Wasps, it is a finger bone that had been part of Sreelakshmi’s hand.

The piece of bone is stealthily picked up from her cremation pyre late at night by her clandestine lover and taken away, put into a secret compartment of a cupboard, and over time, forgotten. The cupboard moves places, a child hides in that very cupboard years later, picks up and holds fast to the skeletal finger not knowing what it is.

Then the piece of bone is taken hither and thither, but always within the confines of the resort, by various people and, as it was once a body part of a writer, it naturally follows that we get to know the stories of the women who inadvertently pick up and carry what they think is a piece of plastic that broke off some toy.

Sreelakshmi is the girl who ate a wasp hoping to flood her mouth with honey. She is the strong, independent young woman who shelved marriage for further studies till all marriage prospects faded away. She is the woman who embarked on a cataclysmic love affair, the woman who started to write `bold’ love stories for a local magazine, the woman who, for a long while, kept the baying world at bay. Till she just couldn’t handle all of it anymore.

Through the bone that was Sreelakshmi’s index finger, we meet Urvashi, trapped in a less-than-happy marriage (“a contractual obligation”) and now in the unpleasant undertow of an affair gone bad, where the lover has turned stalker. We meet the little girl Megha, traumatised by abuse at the hands of the army orderly in charge of the children who travel by the army school bus; she is the one who hides in that cupboard and dislodges that piece of bone. We meet Maya struggling to make sense of every day without a beloved husband of a late-in-life marriage, struggling to handle her 38-year-old autistic son. We meet Najma, whose face and life is scourged when acid is thrown at her by an angry admirer. And then, we meet Sreelakshmi herself, gatherer of wasps and wantonness, “forever feeding on the memories of anyone who holds me long enough because it’s easier to lose myself in other people’s stories than dwell on my own.”

Something sour has crept into their fraught lives, and the emotions run all over the pages; there is nothing subtle about the emotions or the women who give in to these emotions. There is less kindness and more bitterness, cynicism in these women’s lives, in their ways of seeing. The heartbreak comes in many forms and the reader engages with it, distressed at what the little girl goes through, wincing at Urvashi’s dilemma, sympathising without any real understanding with Maya.

While the stories all segue into each other fluidly, Nair calibrating the accounts with finesse, there are some characters who wander in, tell their tales and then wander out, without leaving much of an impression. The main story would still have carried enough heft without the presence of characters like Molly and Theresa, Liliana, the suave diplomat’s not-so-suave wife, as well as the young badminton player. After her first encounter with the man who would go on to become her secret lover, Sreelakshmi returns home from an outstation trip, unpacks her trunk and sighs into it, all the unsaid words and nerve-end longings, all the secret desires and the weight of unshed tears. And the reader, who knows Sreelakshmi is dead, feels a sharp pang about the sudden extinguishing of this interesting brief life.

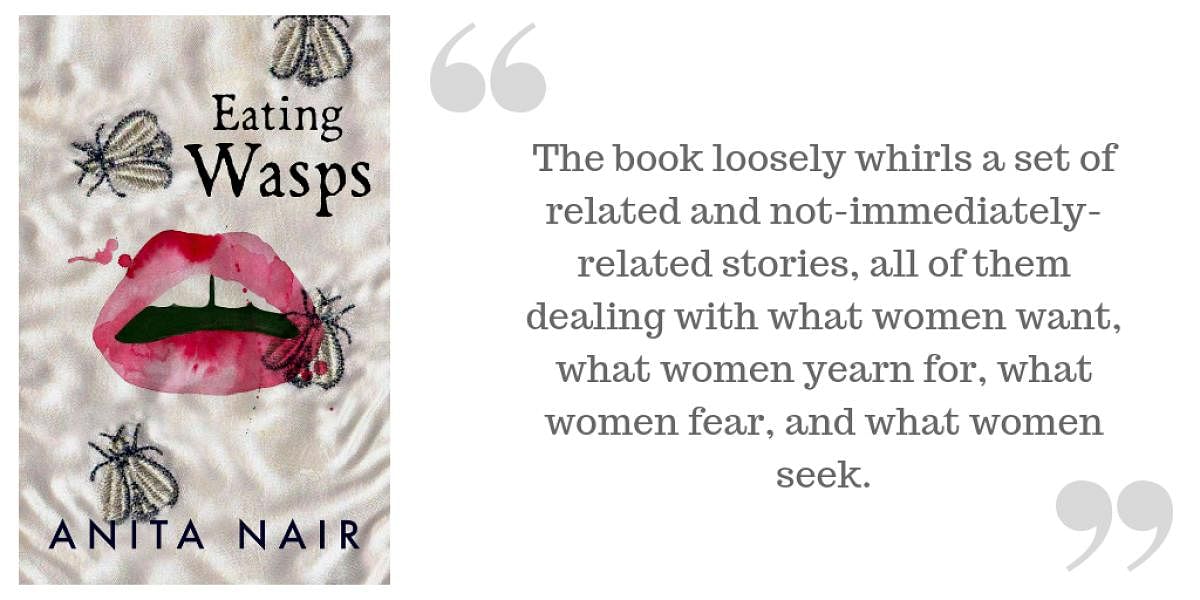

Oh, and the luscious cover deserves a special mention.