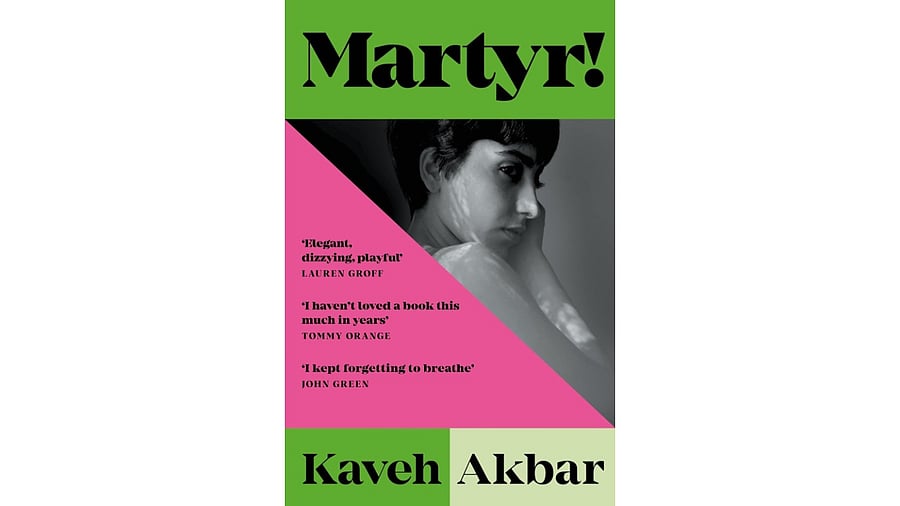

Martyr!

Credit: Special Arrangement

Cyrus Shams is lying defeated on his fetid mattress like a weather-beaten soldier. He is suicidal but does not want to waste his suicide. He waits, therefore, for God to give him a sign, so he can start life all over again, sober this time. His life is fundamentally engineered by one of the precipitating events of the book — his mother’s plane, an Iranian commercial airliner that is shot out of the sky by USS Vincennes, a missile cruiser, killing more than 270 passengers on board.

Martyr by Kaveh Akbar is many things — a story of recovery, addiction, empire, and legacy. What it is not though is a martyr’s tale. Not in the conventional sense at least. Cyrus Shams is an Iranian immigrant in the US raised as a Shia Muslim, to which martyrdom is central. It is venerated especially around Imam Hussain, grandson of the Prophet who was martyred in the battle of Karbala. Kaveh Akbar points to the politicisation of the word martyr in Iran and how the current regime weaponises the theological implications of the word.

When asked about the book’s genesis, Akbar exclaims, “there has to be something that’s not a ‘thing’, that won’t slip right out of the hole that a human body is, something bigger than a man’s ego.” That thing can be art, love, justice and so on. Justice then, is a great occasion for martyrdom. Replacing the sword with a pen, his protagonist Cyrus intends to write a book, ‘something about secular, pacifist martyrs. People who give their lives to something larger than themselves.’

When Cyrus learns about a certain exhibit called Death Speak — of an artist performing her own dying at the Brooklyn Museum, he pursues her to make sense of his feelings. This becomes, in a loose sense, the narrative superstructure of this novel, upon which the characters’ darker interiority and comedic moments play out. It is said that the artist must metaphorically experience their own death for their art to be truly born and thrive; otherwise, their conscious presence might hinder the art’s potential. Even Ferdowsi, the great Persian poet, whose story is so beautifully narrated in the interlude, gains respect only after his death.

The idea of a noble life

Dreams too, make for an important part of Cyrus’ conscience. Sleep becomes metaphorical as it often is used as a narrative device to propel the story forward. According to Akbar, it is rather ‘American to discount dreams since they are not built of objects, of things you can put in a safe.’

For America, which champions individuality, it is absurd to think otherwise. Nothing belongs more to an individual and less to an empire than dreams. This introduces another overarching theme of the book: the cruelty of the Empire. The longer people live, the longer the Empire can exploit their resources. If everyone were to die a noble death, the Empire could no longer valorise them. Cyrus Shams is a young man who wants to have a noble death which is in direct opposition to the American idea of a noble life.

Kaveh Akbar offers insights in an interview about language. He says, “The language of Twitter (now X), for example, is the language of the Empire being shot at you from a fire hose. It’s teaching you that language doesn’t have any integrity or history. Literature on the other hand slows down your metabolism of language.”

In the novel, too, Cyrus’ concerns are telling of what art has come to mean today. The idea of dying is an ugly one when compared to modern ornamental concerns of craft at large. ‘That beauty is the horizon towards which all art must march.’ Dying of an artist as a performance in all its purity and simplicity is a wake-up call for the fact that language fails. “Sometimes the bigness of a thing is too much for a language, for paint, for art,” he says, “You just have to say it plainly: “O Muslims, I am sad tonight.” That’s what Death Speak is. Being present. Saying it plain.”

Of his being neither here (the US) nor there (Iran), the poet-novelist Kaveh Akbar says that this experience lends to him as an artist a kind of ‘liminality that’s powerful as a defamiliarist engine.’ Like all debut novels are to a certain extent, this one too tends to take an autobiographical bent. But it would be a fallacy to substitute Kaveh for Cyrus. The narrator remains distinct from the author owing to an ingenious impersonality that Martyr ultimately achieves.