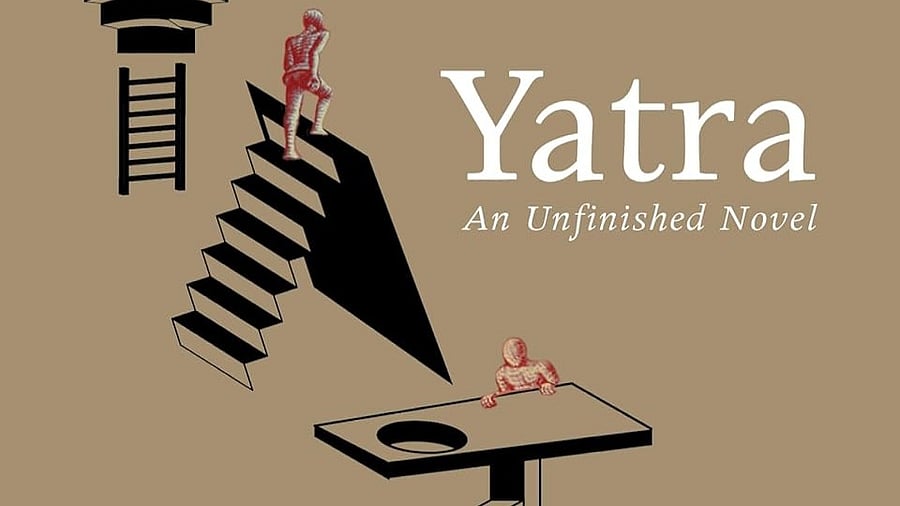

There is much to recommend Yatra: An Unfinished Novel by Harikrishna Deka, translated from the Assamese by Navamalati Neog Chakraborty. The book is a thinking man’s treatise on life, living and the condition of man as one human vis-à-vis another, culturally removed, different in myriad ways. Is there something intrinsically human that transcends culture, beliefs and indoctrination? How are connections established in a world of essentially disconnected individuals? How do we assimilate tribals, the radical left, government machinery, idealism and ground realities in the perplexing mix that is democratic India?

Much of the book is rumination and abstract theorising. Some of it is wordplay on topics as they come up in this rudimentary storyline. In its torpor and spread, the writing and how schisms are presented feel dated. And yes, there are a few characters that are brought in to say their stories in a bid to further the freewheeling writing on fissures, exploitation and the ordinary Indian pitted against government machinery. Some of it seems unintentionally amusing given that in real life the author has been a DGP and firmly on the side of governments, their failures and all.

At the centre of this web of unconnected thoughts and observations is the main character, a teacher and writer. To this writer is sent a letter by another writer/ traveller who shares the story of an undiscovered tribe deep in the mountainous jungles.

“They were such a backward race of people, so divergent from mine. They belong to the Stone Age in their existence…. It’s stalled all the urges of any kind whatsoever to move ahead. That was what I concluded as I watched them day and day out.… Their lives then would be unbearable, and the ruinous aspect that I could see before my eyes would certainly be the final aggravation together with all other dreary aspects that they would be left high and dry on the shores of hunger and subjugation. Their existence may be totally wiped off.”

And yes, a woman is provided to the traveller for comfort in that tired old trope of sexual capitulation to the outsider.

These missives comprise a good part of this work. Despite these us-versus-them views on the tribals, the traveller’s heart is in the right place. He wishes to save the populace from annihilation at the hands of mining giants.

A major character in the story is Mahendra, an idealist former student who now works for the disadvantaged. In a way, he is the doer and conscience-keeper among this sparse cast. The author runs into him quite by accident when he faces a roadblock by protestors on his way to a book-related function at Lakhimpur. This form of activism lands Mahendra in jail. Through a brief interaction, our writer discovers that it is mediated by the former that the other writer had got his contact details. Now he is keen on meeting his correspondent.

Circumstances urge Satarupa to opt for journalism. She meets a local man who reminds her of a figure from her childhood and by association, she calls him Jaggu. To her dismay, she learns that Jaggu’s daughter Lacchmi had been raped by the local strongman and politician Mahajan’s son and while the girl is determined to fight him in the courts of justice, her father would rather take the monetary compensation, for it could change their lives. When Jaggu falls terribly ill with his asthma attack, he is given up for dead because the poor have no access to medical help. Yet Jaggu isn’t his real name and no one cares to know what it really is.

The choice of an author as the protagonist and furthering the narrative through correspondence between two writers enhances the discourse because authors belong both nowhere and everywhere and we learn to see the world through their works. With their effete morality, they are as vulnerable as the poorest in our society, the ones whose stories they seek to retell. Perhaps, as the title suggests, all of it is an unfinished journey.