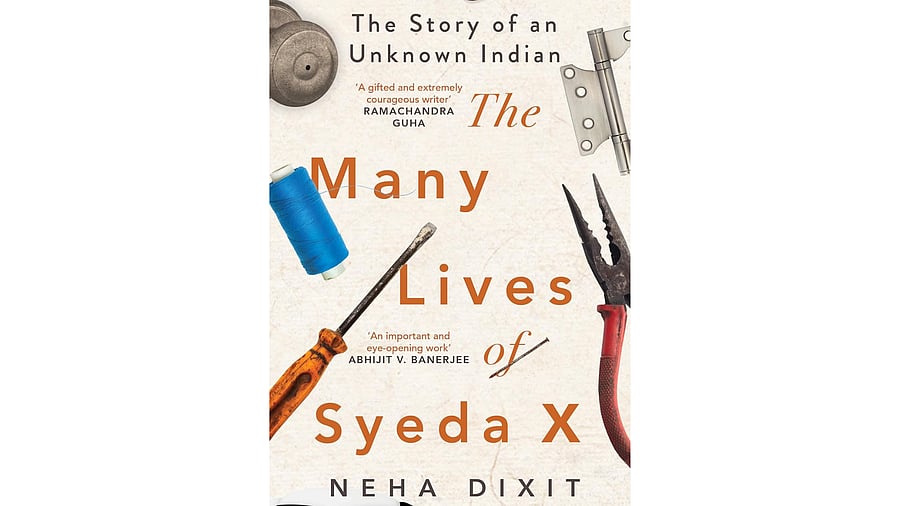

The Many Lives of Syeda X.

Credit: Special Arrangement

Veteran journalist, prize-winning ‘shoe-leather’ writer of many articles that have caught the startled attention of the authorities and the public alike, Neha Dixit`s first book is everything one would expect from her: an excellent piece of reportage.

There is no soft immersion involved here. We are almost immediately introduced to the protagonist of the book, Syeda. Within a few pages of our meeting her in her hometown Banaras, the Babri Masjid is brought down and the riots that follow have Syeda and her ne’er-do-well husband Akmal leave their town and their weaving looms, to land up as itinerants in impersonal, cruel Delhi.

From then on, we stay with this slight woman with a spine of steel who goes out and takes whatever job she can find to keep her family alive, till the 2020 Delhi riots happen. It’s a far-from-cheerful existence. We watch as Syeda gives birth to two sons and a daughter, we notice the sons are anything but a staff of support to her as she grows older, we see Akmal going down the slippery path of no work and dependency on drink.

Syeda takes on an astounding 50 jobs in 30 years. They run the gamut of trimming loose threads of jeans, cooking namkeen, making gajak, cleaning raisin stems, shelling almonds, making tea strainers, doorknobs, pressure cookers, photo frames, cycle brake wires, door hinges, washing clothes, working at an abortion clinic, pasting bindis, colouring wedding cards, packaging spurious face creams; the pittance she earns as salary makes us wince hard. With no other option, Syeda becomes an all-in-one: worker, material manager, production manager, finance manager, personnel manager, marketing manager, and chief executive of her business.

Alongside Syeda, we meet other feisty women who have willy-nilly become the unappreciated backbone of their families, women like Raziya and Radiowali. They become Syeda’s support system. However, we soon realise that Syeda’s pragmatism and prudence are her support systems in a world where the odds are stacked against her: she’s Muslim, a woman, poor and barely educated. She has no political opinions simply because she cannot afford to hold any political opinions; struggling to hold on to these will-of-the-wisp jobs takes all of her time and energy. At one point, after yet another calamity, she tells the author: till then we had known hunger, grief, sorrow and frustration, like everyone else. But this was the first time we experienced terror. Because of our religion.

Dixit peppers the book with gung-ho shoulder heads proclaiming the many steps India has taken towards progress and prosperity. Juxtaposed alongside Syeda’s dismal trajectory, a life lived under constant corrosive tension in which progress and prosperity are marked by their absence, the irony is unmissable. Add to that the jingoism, communalism, and hatred that has become normal in New India, and the picture is anything but bright.

The final chapters of Syeda’s story have the focus shifting to her daughter Reshma who, despite doing well in school, is forced to take up a cleaning job at a mall. Equal parts resentful of life’s cruel games, equal parts pragmatic like her mother, through Reshma, we realise the baton has been picked up, and the race continues. And above all, hope floats, in the struggle to make life livable, tolerable.

In recent times, this reviewer has not come across a book that so forcibly brings the term ‘check your privilege’ to mind. It is both humbling and shameful to see what little space the Syedas occupy, the social discrimination they face, and how little impact government policies have on them. Dixit’s work is richly sewn together with statistics, all of which expose the hollowness of claims of inclusivity. We learn that almost 82% of working women in India are concentrated in the informal sector. She adopts an impersonal reporting style that does not take away an inherent compassion for those like Syeda who live their fringe lives on the edges of our consciousness. My book was born out of a lack of an intersectional gender lens in the mainstream media, says the author. She has brought Syeda to the attention of a people who have rendered her invisible since that suits them; those people include us, and the sooner we become aware of it, the better.