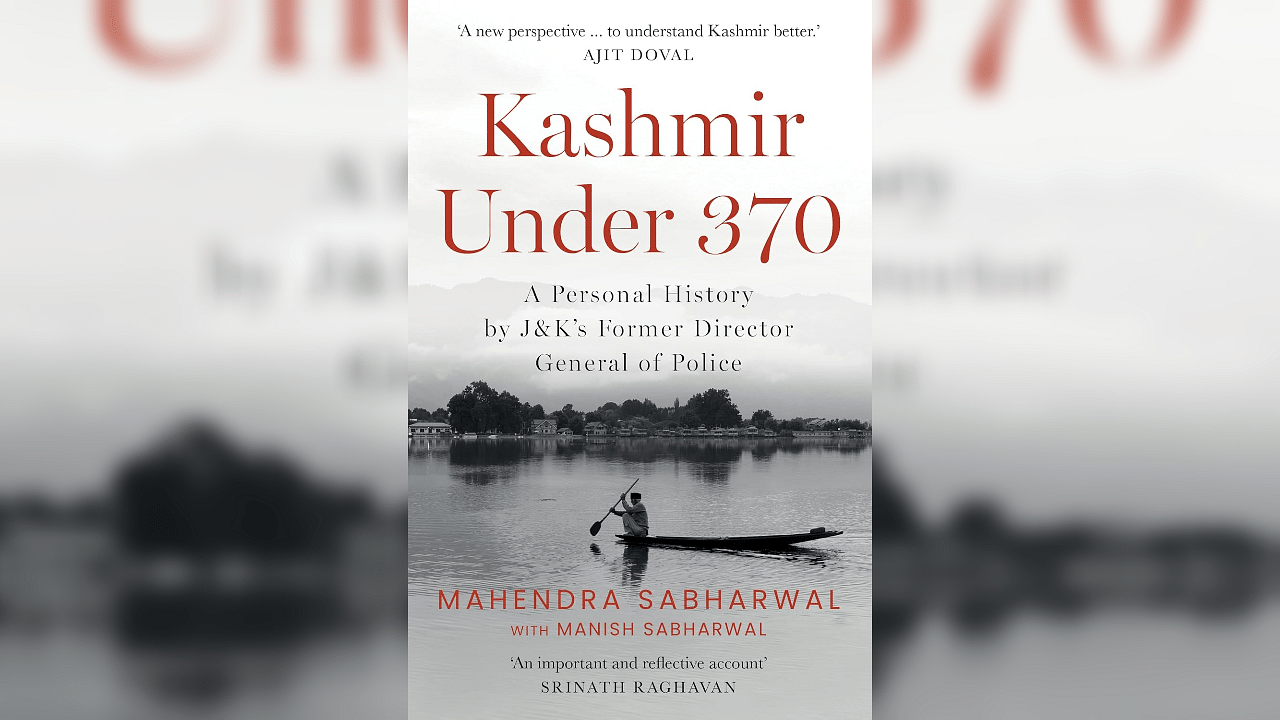

Kashmir Under 370

Credit: Special arrangement

No matter how you choose to examine it — through humanitarian compassion, geopolitical strategy, or internal security concerns — Kashmir resists resolution, a true catch-22. Right off the bat, the author expresses how his age has brought him a “deeper appreciation of the concept of anekantavada, the multiple versions of truth. Where you stand on an issue depends on where you sit.” It’s a reminder worth holding on to as you read this book, by no means an authoritative account of the history of Kashmir under 370, but an important one nevertheless.

After all, Mahendra Sabharwal’s vantage point is unique. As the first IPS officer to be directly assigned to the Jammu and Kashmir cadre in 1964, he has decades of firsthand experience within J&K’s administration. He has seen seismic shifts: political upheavals, state and central elections (or the failed attempts thereof), the surge in militancy, tightened borders, and the exodus of Kashmiri Pandits — the list goes on.

Eschewing linguistic embellishments for a straightforward narrative, Sabharwal outlines how “peace in J&K was undermined by five interconnected forces”— troubled Pakistan, Cold War geopolitics, radical Islam, fraught federalism, and separatist politics.

You, the reader, receive a firsthand account of the police force in J&K and how it evolved into a more confident and well-developed entity during Sabharwal’s tenure. His narrative takes you through critical moments — from the Hazratbal sieges of 1993 and 1996 to the ever-changing leadership in J&K, the line of Indian prime ministers, and the relentless conflicts and politics with Pakistan.

As you read, certain binaries emerge. Wahabi Islam: bad. Sufi Islam: good. Article 370: bad. Its abrogation: good. Pakistan: adversary. India: defender. As with most contentious issues, the answers are never simple, and therein lies the chief criticism of this memoir: it can be all too simple all too often.

You find the ever-so-familiar descriptions of the beauty of the Valley: “Kashmir is a land where the divine and nature’s bounty seamlessly merge. It is blessed with soil and a climate so fertile that even a planted chicken leg might sprout.”

Some blame is shifted on the local leaders. “There is one answer to his questions: local politicians have treated J&K like a jagir rather than an amaanat. A jagir is a personal property you can do whatever you want with (...) But the idea of amaanat has no room for ownership.”

Pakistan and Islamist fundamentalism bear the brunt of the remaining, with the religion existing in two binaries: “The Jamaat-e-Islami were followers of Wahhabi fundamentalism, which contrasted with Kashmiri Ahle-et-Quad (those who believe in saints and shrines).”

Make no mistake, these factors do play a role in the tangled state of affairs in the state, but they are far from the only influences at play.

Conspicuously missing are references to the drawn-out internet blackouts, curfews, dwindling trade, widespread evictions, and the destruction of homes — not to mention the regular arrests after the removal of Article 370 that have become synonymous with control in the region.

The central government escapes scrutiny. What you find instead is an abundance of praise for the current political dispensation, a celebration of surgical strikes and the nationalistic ethos. “But this is changing; a massive renovation of India’s intellectual, security, financial, diplomatic, investment, welfare, and economic infrastructure is underway.” If you take this memoir at face value, achche din for Kashmir is not just on the horizon — it’s already arrived.

Sabharwal’s role as an IPS officer shapes his perspective in ways that are both expected and limiting. While it lends undeniable credibility rooted in decades of state service, it simultaneously narrows the objectivity of his account.

What you get is a history told from the halls of power, where the grand retelling of state-driven milestones drowns out the voices of ordinary Kashmiris. Indeed, what’s missing are the voices of Kashmiri civilians — the ones most affected by the policies and conflicts. The focus on top-down storytelling leaves their everyday experiences on the periphery, unseen and unheard.

If this is the only book on Kashmir you pick up, you’ll only find a slice of the full picture. Yes, it’s suited for casual readers and scholars alike, but only when paired with other works that lend voice to those who live the conflict daily. To understand Kashmir is to grasp not just the narratives of power but the testimonies of its people.

Without that, the story is never truly whole.