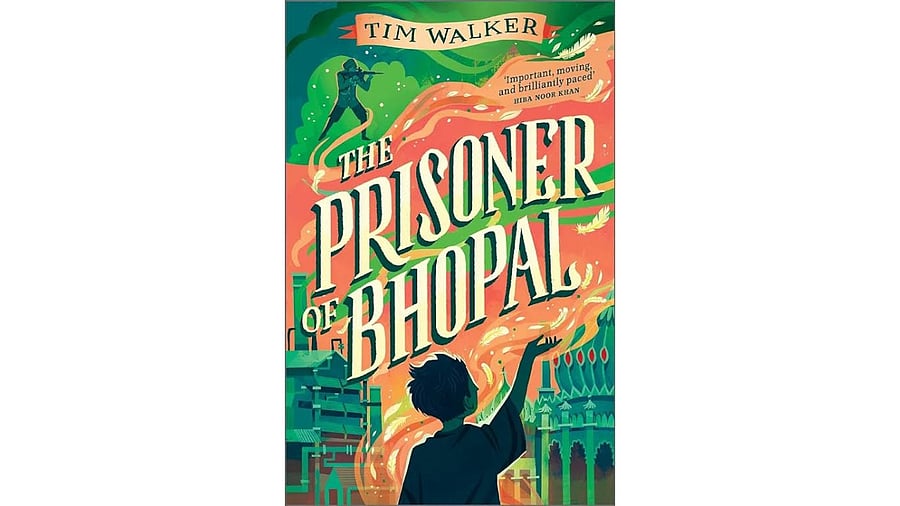

Cover of the book 'The Prisoner of Bhopal'.

What was the inspiration for the story?

The inspiration for the story was a small personal connection I had with the Bhopal Disaster. As a young designer working in a London design company in 1984, I was asked to arrange a photograph of an Indian farmer and some text for the back of a pesticide sales leaflet. The client was Union Carbide and the pesticide was similar to that produced at the Bhopal plant. Whilst completing my task the disaster was announced over the radio and we were instructed to stop our work for Union Carbide. When the causes of the disaster, and Union Carbide’s culpability, became known, I finally became aware that companies were capable of putting profit before the health and safety of their employees. To me, this was a horrible revelation. Seeing the same pattern of behaviour continuing decade after decade, despite the disaster, has inspired me to write this book. Inspiration for the story itself began by seeing a parallel between the devastation caused by a company — as witnessed tragically in Bhopal — and the devastation caused by war. Landscapes destroyed, and lives lost, in this case to poisonous gas. Creating an additional World War One storyline to explore this parallel followed naturally from that idea.

Recently there has been a spate of films and series on the Bhopal Gas tragedy...How does your book compare to these?

Unlike much of what has been written and filmed about the disaster, my book is for children, perhaps aged 10+, although adults may like to read it too. It contains an element of magical realism intended to draw them into the story and spark their interest in the Bhopal disaster and the issues it raises. One day, some of those children will become industry leaders, and I hope that knowing about the disaster may help them make better decisions than those made by the executives at Union Carbide. I think I am trying to do many of the same things the producers of those films were trying to do — raise awareness, for example — but to a younger audience during their more formative years.

What was the kind of research you undertook for this book? Did you visit Bhopal before writing it? Did you speak to the Union Carbide officials?

I spent about a year researching the story — the Bhopal disaster, Indian life and culture across both timelines, the lives of Indian soldiers during World War One and many smaller elements, such as the wonderful world of clouds. Most of my research was done by reading books, Indian newspaper accounts of the disaster given by its survivors, and letters home from Indian soldiers recorded in the National Archives. I also visited the Royal Pavilion in Brighton, England, where injured Indian soldiers were cared for during World War One.

I didn’t visit Bhopal, believing that the vision I had of the story, and thus my ability to write the book, would not survive contact with the reality of the modern city. Uncovering what happened that night in 1984, talking to engineers, residents, and executives, was done decades before me by two world-class authors and journalists, Dominique Lapierre and Javier Moro, who lived in Bhopal whilst producing their outstanding account Five Past Midnight in Bhopal. The authors were involved in supporting the Sambhavna health clinic in Bhopal, which continues to treat those affected by the disaster, and their book was one of the cornerstones of my research.

Tell us a bit about your writing process...what are the challenges you faced while writing this? What was the fun part? How did you find your style/groove?

My writing process is slow and painstaking. I take a long time to get things right, and The Prisoner of Bhopal went through 14 drafts before it was ready, so I’m not sure I ever found a ‘groove’. As a former designer, I see a lot of my stories in terms of pictures — scenes and characters which I will often sketch out before I start writing. Often, I will use these visual scenes as stepping stones, writing a story that links them all together. I found The Prisoner of Bhopal a challenging book to start and the task ahead quite daunting. What helped me was to write the last page — a poem — first. This gave me a goal, a light at the end of the tunnel that I could travel towards. Whilst the subject matter is tragic, there is joy in learning about different lives and cultures and creating characters that you can get to know and care for.

Who would you say are the authors you are inspired by? And why?

In the UK there are two children’s authors who have inspired me — Michael Morpurgo and Philip Pullman. My granddaughter, Lyra, is named after the main character in Philip Pullman’s most famous work, His Dark Materials. Both writers produce books that invite children to explore important topics, an aspiration which I share. The Life of Pi, by Yann Martel, also inspired me — I have read the book, watched the film and seen the play. It is about an Indian boy from Pondicherry and its evocations of India are wonderful. Whilst researching for The Prisoner of Bhopal I also enjoyed reading the tales, myths and legends of India contained in Madhur Jaffrey’s Seasons of Splendour. It reminded me that in stories, anything is possible.

What next? Do you plan to write more historical fiction?

At the moment I’m writing a children’s adventure set in the Niger Delta in Nigeria. Parts of this once lush paradise have been trashed by the oil industry, leaving land once fertile and creeks once abundant in fish, full of oil. Again, like Bhopal, it is the local inhabitants who have paid the price for the folly of others, and I would like to tell this story too.