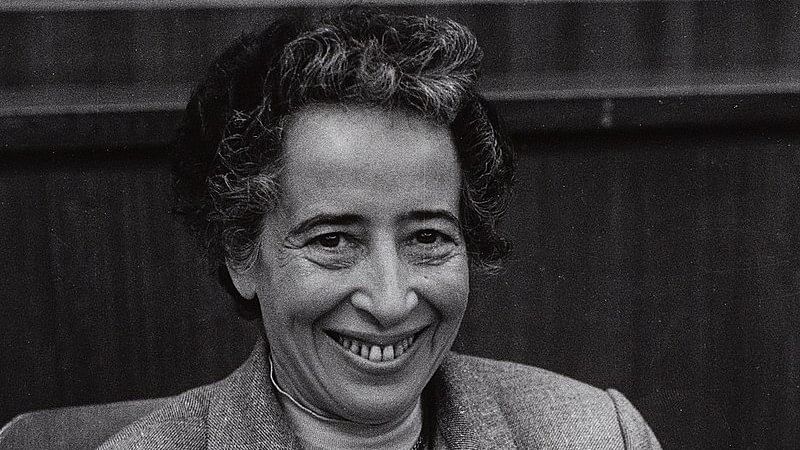

Political philosopher Hannah Arendt.

Credit: Wikimedia Commons/By Barbara Niggl Radloff

“My father travels on the late evening train

Standing among silent commuters in the yellow light

Suburbs slide past his unseeing eyes…”

These evocative lines from one of Dilip Chitre's most renowned works—Father Returning Home—are perhaps an apt depiction of modern man's alienation, or as Chitre himself puts it: "man's estrangement from a man-made world".

Working tirelessly to make ends meet for his family, the man in the poem finds himself worn out from the unending cycle of abrasive, mundane labour: when he wearily reaches home, it dawns upon him that he has neither a bond nor any connect with his family, the very people he is working for. Alienated from his own labour, and from his family, loneliness seeps in further and he goes to sleep, and the cycle begins again.

Penned in the 1980s, Chitre's poem resonates strongly even now and captures an all-too-familiar feeling. Wrapped up in our own lives and saddled with the burden of our daily grind, we often find ourselves isolated and alienated from others, so much so that loneliness has, in so many words, been described as an epidemic of the 21st century.

Yet, loneliness hasn’t been the only defining feature of recent times: the 21st century has been marked by unimaginable levels of economic inequality, a hitherto unseen rise in populism, and the proliferation of totalitarian or pseudo-totalitarian regimes in many corners of the world.

But what does loneliness have to do with any of this? How is a subjective, psychological phenomenon connected to material and political phenomena? Baffling though it might sound, research suggests that loneliness is indeed tethered to politics, with the linkages between the two coming to the fore during the political turmoil of the mid-20th century.

In the spring of 1961, a man named Adolf Eichmann was presented before a court in Jerusalem, Israel. Colloquially known as the ‘mastermind’ of the genocidal ‘Final Solution’ that left over six million Jews dead during the Holocaust, Eichmann’s reputation preceded him and the trial was attended by hundreds of people as many Jews wanted to witness what the perpetrator had to say.

Sitting among this crowd was Hannah Arendt, a budding political theorist struggling to make sense of the unprecedented political churnings of the 20th century. Born into a Jewish family in Hannover, Germany in 1906, Arendt had to flee her homeland in 1933 fearing persecution from Adolf Hitler’s Nazi regime. She eventually settled down in New York in 1941 and it was here that Arendt started putting pen to paper and began publishing various essays attempting to unpack the political currents of the times, totalitarianism in particular.

An astute observer and no stranger to the excesses of Hitler’s brutal regime, Arendt found that the political developments of the 20th century were unprecedented: unlike systems of government in the past, including oppressive ones such as tyranny, totalitarianism was a different beast, one that, according to her, had not reared its head prior to the emergence of the Nazi and Stalinist regimes.

With the Nazi regime slowly taking root in Germany, Arendt helped communists flee the country by turning her apartment into an underground pit stop for them. She was also briefly arrested by the Gestapo which ultimately forced her to flee the country and make her way to Paris, where she worked for various Jewish refugee organisations. However, her stay in Paris was short lived as France fell to German occupation in 1940, forcing Arendt to make another move. She arrived in the United States in 1941 where she began writing one of her most renowned works, The Origins of Totalitarianism. This book, published in 1951, was the first of many acclaimed works by Arendt and would go on to become one of the most influential works of political philosophy in the 20th century.

In Origins of Totalitarianism, Arendt divides the book into three sections—namely, antisemitism, imperialism, and totalitarianism—and delineates the rise of totalitarian regimes such as those of Hitler and Stalin. But the main crux of the book is how an individual’s loneliness can become ‘fertile grounds’ for the emergence of totalitarian regimes. She argues that when man is devoid of human companionship and is living in isolation, cut off from the world and its lived experiences, he becomes susceptible to certain ideologies that are prevalent and dominant in society.

In her 1958 book The Human Condition, which was also divided into three sections, she explains that a man’s life is divided into three parts: Labour, Work and Action. ‘Labour’ corresponds to the biological processes that are required to be carried out by man for the satisfaction of material needs and desires. ‘Work’, meanwhile, corresponds to man building the physical world he lives in.

The last one—‘Action’—is of the utmost importance: for Arendt, this corresponds to man’s ability to voice his opinions and formulate his thoughts. Arendt believed that lived experience consisted of these three fundamental facets.

However, she postulated that the ‘Action’ part of a man’s life had diminished over the years. Preoccupied with labour and working in a vicious cycle, disillusionment had taken hold and the lack of space to engage in the political realm had driven him to the point of cynicism. At the time she was writing, Arendt observed that the disillusioned man found problems in every nook and cranny as he had no views of his own. Alienated from everybody, man had grown weary and cynical, to the point of complete disengagement from the social and the political.

Yet, at the end of the day, man is a social creature in need of a sense of belongingness. Thus, when certain ideologies or grand narratives that conform to his cynicism of the world are promulgated, he grasps at these because they validate his views.

According to Arendt, most of these ideologies are detached from the perceptible and material realities of this world. Rather, they seek to control and predict the tide of history by injecting some ideological meaning into everyday actions. These ideologies posit that there exists a ‘truer reality’ or goal beyond perceptible lived experience that people must strive towards, and lonely, cynical and disillusioned people, devoid of their own sense of judgement, make for the best subscribers to such streams of ideological thought. .

She writes: “The ideal subject of totalitarian rule is not the convinced Nazi or the convinced Communist, but people for whom the distinction between fact and fiction (ie, the reality of experience) and the distinction between true and false (ie, the standards of thought) no longer exist.”

To this day, The Human Condition is held in high regard and considered to be one of the most original pieces of political thought.

But Arendt’s story doesn’t end here. In 1960, Adolf Eichmann was captured from Argentina by Mossad agents and brought to Israel. When the news finally broke of his arrest and the subsequent trial, Arendt immediately wrote to the editor of The New Yorker, offering to cover it. She finally wanted to confront “the realm of human affairs and human deeds”.

Decades after fleeing Germany, Arendt saw this as an opportunity to see a Nazi chief in the flesh. Thus, she flew down to Israel in 1961 and by way of trial, began writing her most crucial work, The Banality of Evil.

Sitting in the courtroom and listening to Eichmann talk about the “deeds” he committed under the Nazi regime was an unkind revelation for Arendt. The world expected Eichamnn to be an incarnation of evil, a devious mastermind, a conniving and ruthless man.

Adolf Eichmann during his trial in Jerusalem, 1961.

Credit: YouTube/Best Documentary

But what Arendt saw was a rather unclever and bland bureaucrat merely following the orders of his superiors. She expected to see a sadistic man but found him to be ‘terrifyingly normal’.

This revelation became the basis of her book. Up until then, the Nazi regime was considered to be an ‘anomaly’ due to the horrific acts they committed. But Arendt discovered that one doesn’t necessarily have to be evil to commit evil acts.

Disengaged from reality, isolated from others and diligently working only to advance your career can drive any man to commit the most horrific of crimes. Thus, evil is not an anomaly, it is banal.

This reportage caused waves across the world, and Arendt was heavily criticised for her approach on the trial and reprimanded for showcasing Nazis in ‘sympathetic light’.

What is noteworthy is that the common denominator in all of Arendt’s works was the centrality of ‘thinking’. She emphasised that one must question their own beliefs and juxtapose them vis-a-vis the reality one lives in. Only then can they break free of the shackles of ‘ideology’ which has been thrust upon them by those who hold power.

She ardently believed in the concept of ‘critical thinking’ and advocated for grounded and critical analyses of any belief to test whether a belief conforms to the reality of society. Without such a critical approach, ideologies far removed from reality may thrive and take hold in the minds of isolated and lonely people.

These ideologies usually begin as mere opinions but soon evolve into prejudices. As aforementioned, when the disillusioned man, disengaged from the activity of thinking, comes across such ideologies, he is immediately drawn to them as they validate his cynicism. Moreover these ideologies promise a better tomorrow by vowing to eradicate all that is ‘evil’ today.

When disillusionment and loneliness grips people, subscription to such ideologies or grand narratives gains momentum as they resonate with people’s cynicism. Soon, these narratives become the dominant ideology, leaving no room for a contrarian view to be discussed, creating fertile grounds for totalitarian views to take deep roots.