Flights

Credit: Special Arrangement

When we think of travel, we usually have a certain kind of image in mind—beautiful scenery, ancient monuments, guidebooks, and posts captioned #wanderlust. But the reality of travel is rarely as perfect as that. “Travel writing” is a helpful shelf in a library, but what about writing about travel that goes beyond that? These writers interrogate what it means to write about movement, and what it means to be a person in motion. Through different lenses, these writers reflect on the specific experience of travelling as a woman—what that means in new cities, in transit, or in places we consider home. Strikingly, these are also all works, or writers, that live between multiple languages—in itself a kind of travel.

What if you had the chance to ask for anything in the world—would you ask for endless adventure? When you make a deal with a demon, precise instructions are important—demons love a loophole. The protagonist of Intan Paramaditha’s The Wandering (translated from Indonesian by Stephen J Epstein) asks for a chance at adventure, and the demon gives her a pair of ruby shoes that will take her anywhere she wants to go.

The Wandering puts you, the reader, in this Indonesian woman’s magic slippers—written in the second person, you have the chance to choose your own story. The choices appear endless. Only, The Wandering cleverly reminds us that some choices are not choices at all. You might choose to visit a certain country, only to be stalled by grounded planes because of bad weather, the harsh reality of a visa, or an overly chatty passenger seated next to you. The protagonist reflects: “For some, the world is indeed very small.” Not so for everyone. Your decisions can only lead you and the protagonist to a finite number of endings, a reflection on ever-increasing imbalances in global travel and mobility, albeit with a supernatural twist.

The reality of travelling as a woman—a brown woman, an Indian woman, an Indian Muslim woman—is what Shahnaz Habib writes of in Airplane Mode: A Passive-Aggressive History of Travel. As evident from the title, this is a playful reflection on travel and migration.

Habib writes about buses, passports, guidebooks, tourists, and carousels with equal curiosity, offering us literary, scholarly, historical, cultural, mythical, and personal touchpoints. She looks at a big-picture view as she locates herself within it, acknowledging and exploring the complex interplay of tourism, globalisation, and industry. When she catches herself worrying that she doesn’t have “the adventurousness and intrepidity required of a good traveller,” Habib stops to ask: “Is there even such a thing?”

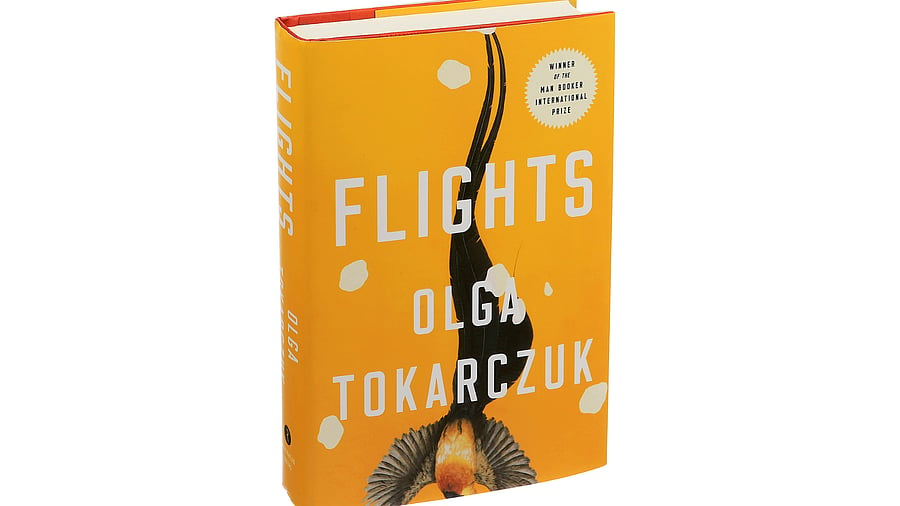

Why do we travel? In Flights, Olga Tokarczuk’s labyrinthine novel, translated from Polish by Jennifer Croft, is the story of people in movement. Written in vignettes, and featuring images of maps, Flights tells us fictional stories of travel and displacement alongside historical ones, punctuated by reflections on modern travel by a nameless female narrator. Is anyone ever really still?

A psychologist the narrator encounters posits that the only way to understand humans is “by placing people in some sort of motion, moving from one place towards another.” By turns funny, fascinating, informative, and cryptic, Flights is a reflection on life seen from outside, or perhaps from above; as we travel on our way away from home, or perhaps towards a new one.

Locating ourselves in a new place is one thing, but for Jhumpa Lahiri, settling down in Italy requires more than just settling: it means taking on a new language as her own. Whereabouts and Roman Stories, the two works of fiction she wrote in Italian, translated into English almost entirely herself, are both stories of people in Italian cities.

What’s striking is although both take place mostly in one city, they are about people in constant movement, stories of lives in flux. In these works, setting down roots is not a guarantee of belongingness—characters (Italian or otherwise) are beset by restlessness; they face psychological and physical versions of racism because of their accents or the colour of their skin; and then they reflect on the meaning of “home.”

(The author is a writer and illustrator. Piqued is a monthly column in which the staff of Champaca Bookstore bring us unheard voices and stories from their shelves.)