A wide-eyed Surya Deva is at the centre, and from him emerge 12 successive concentric circles picturing a zillion things, beginning from the 12 raashis or signs of the zodiac, the rituals, traditions and festivities specific to each of these periods, events of the cropping cycle, and just about every facet of life — accurately, in synchrony with the time frames associated.

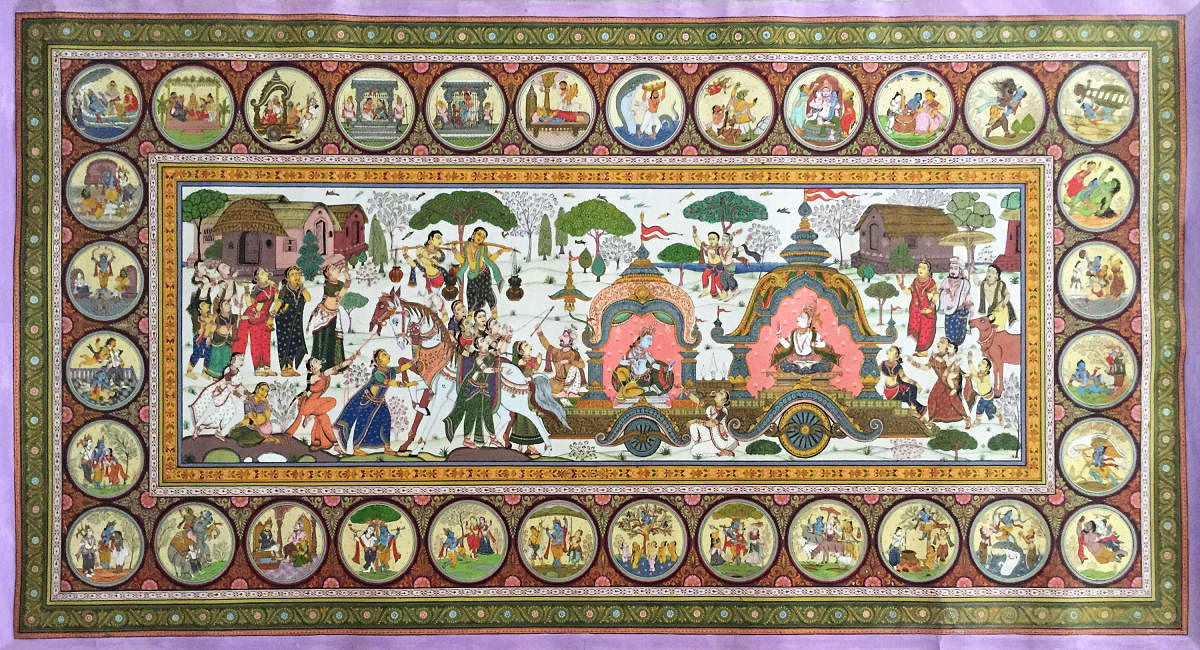

Virtually a cosmic calendar, all of this finds place in a 48X48-inch painting lined by an elaborate border that narrates more stories! Such is the overwhelming possibility that a patachitra can hold. It’s Odisha’s traditional art form that dates back to the 5th century, or perhaps even earlier, and narrates concepts and stories from Hindu scriptures.

This particular painting, ‘Cycle of Seasons’, rendered by chitrakar (traditional artist) Gangadhar Moharana, got sold for nearly a lakh-and-half rupees. For Gangadhar, who had spent countless hours spread over months hunched over this canvas, all the while struggling against poverty and keeping the wolf away from the door, the joy that this transaction brings is unprecedented.

‘Cycle of Seasons’ is not the only one. At Chennai’s Forum Art Gallery, many exquisite, spectacular and intricate patachitras that were on display recently, rendered by meticulous chitrakars from Raghurajpur and a few other villages in Odisha, found appreciative and happy buyers.

Aided by the Crafts Council of India, a couple of these chitrakars had come to Chennai to give a live demonstration of patachitra. One of them is 50-year-old Sharath Kumar Sahoo from Raghurajpur, a village in Odisha that has every family, and every member of the family, involved in some aspect of patachitra. This includes preparing the pata/patta or canvas, which is basically two layers of cotton cloth stuck together by a layer of ground chalk in resin, binding to give stiffness to the cloth, after which water is sprayed and the pata is pressed over with stone and sun-dried.

Finally...

This is done three times, and the pata is ready for the chitra or painting. Another major task lies in aggregating and developing the five primary natural pigments used in patachitra — white from ground conch shells, black from lamp soot, and yellow, maroon and red from stones sourced from the jungle. After grinding, the pigments are mixed with resin tapped from local trees in coconut shells.

This is done using fingers. “Only such a process will bring out the full glory of the pigments,” informs 29-year-old Prasanta Moharana from Nayakpatna, a village close to Raghurajpur. As and when they paint, the chitrakars add water to enable application of the colours on to the canvas. Next to the primary colours, blue, green, orange and pink seem to be the favourite secondary colours used. Some chitrakars extract pigments from seaweed and other plants too. These pigments, bound and locked in resin, will never fade and the paintings will virtually last forever… long after the walls they have hung on crumble.

Some chitrakars render work on palm leaves too.

Prasanta informs, “Engraving on palm leaves is a far more laborious and delicate job. First, the palm leaves are boiled in water with turmeric, until the green colour is leached off from the leaves, and then dried in the sun to ensure that the leaves will not be attacked by insects”. Engraving is done using a sharpened iron pen. Ink is then applied on the engraved leaf and washed off, and the ink remains in the engraved areas. Patches of palm leaf get cut off with an iron knife to create depth, and the palm leaves are stitched together like blinds.

Jatripat was the ancient name of patachitra. And back then, painting was done using wood brushes. Somewhere down the line, squirrel-hair brushes began to be used and with that, the scope for detailing rose enormously.

Glorious complexity

Such elaborate processing was used to create stupendous works of art. While the many stories of Hindu deities Jagannatha, Krishna, Vishnu, Shiva, Hanuman, Radha, Parvati and Sita, and the magnificent sculptures and architecture of the Konark Sun Temple form the primary themes of patachitra, folklore too inspires patachitra compositions.

The complexity of this art’s imagery is unparalleled, and a single patachitra painting often narrates several stories within its frame.

Many among these chitrakars happen to be Lalit Kala Akademi and National Award winners. They weren’t making much money from their small and simple patachitras either.

“Touts and commission agents take the pieces on consignment and pay the artists months later, at much lower prices than the art deserves,” informs Suguna Swamy, who had joined the Crafts Council of India after retiring from O&M.

The weekend workshops that CCI organised in these villages to train these youngsters in their ancestral crafts found very few takers. The disenchanted younger folk were moving away from patachitra.

Around this time, Suguna came across an astounding and elaborate patachitra “languishing in a dusty loft in an award -winning artist’s home.” She shot a few pictures of the painting and posted it online. Seeing this, art collector Ashwin Subramaniam bought the painting, paying the asking price immediately!

The two then decided that they had to create a platform for these fabulous art works in a metropolis, because that is where the buyers are. They commissioned the artists to create the complex patachitra art they were capable of.

Pointing at an elaborate work rendered by Sharat Sahoo, a senior chitrakar, Suguna Swamy remarks, “Notice how he is working inwards from the border. It requires intelligent and exact visualisation of how the central image and story will emerge, with perfect proportions and division of space. There is no room for correction, should his judgment of space or line go wrong. Not like oil painting!”

In January 2015, Suguna and Ashwin arranged the display of 47 such paintings at a Chennai gallery under the tag Jagannatha.

“The chitrakars sent their works without asking for advance money; the gallery offered the display space for free. “A total 44 of the 47 works were sold out in no time and numerous more works commissioned,” Suguna says happily. The artists’ payment, with no deductions, was credited immediately to their bank accounts. Suguna informs.

January 2019 saw Jagannatha’s second exhibition. “After the success of Jagannatha, there has been a surge in the applications for the craft workshops from both girls and boys in Raghurajpur. A palpable new pride in their art heritage and the livelihood it promises are emerging. They are also using their education to do their own marketing, via email, WhatsApp and Instagram. Middlemen are being rapidly elbowed out”.

Hopefully, the glorious complexity of patachitra will endure.