Adoor Gopalakrishnan — A Life in Cinema is a biography of the famous Malayalam film director. Written by senior journalist Gautaman Bhaskaran, this book attempts to give us an idea of the man behind such critically acclaimed films as Elippathayam (The Rat-trap), Mukhamukham (Face to Face), Anantaram (Monologue), and Mathilukal (The Walls), to name just a few.

Adoor writes in the foreword to this biography that it is not an easy proposition for a journalist to write a biography. “In fact, there is nothing in common with the profession of a journalist’s pursuit here,” Adoor writes, “A newspaper ‘story’ is for quick and casual consumption...a book, on the other hand, can make a claim to a permanence of sorts.” I could not help but think how true that was, and how perhaps Bhaskaran, after his many years of covering international film festivals, would have wanted to sit down and put something solid and serious about a film-maker in a book, rather than a newspaper column, because as Adoor says in the same foreword, “...yesterday’s hot story is already old and cold.” There is an old-world air to Bhaskaran’s writing that is not much seen in these days of emails, blogs and social networking sites. That style of writing sets the tone for the entire book. While the first half of the book tries to delve into the early years of Adoor’s life, the entire second half discusses all his films. And while I do say the book is divided into two sections, this fact is apparent only when you are halfway through the book, and suddenly there are chapters discussing a film in each. Why it bothered me is the fact that the book was going quite well, and one was beginning to understand the kind of person that Adoor is, when abruptly the book starts delving deep into each film, chapter by chapter.

Not that the man behind the films does not come across — he does, but each chapter is confined to a particular film, and there is no formal transition into this section. This begins with the chapter on Swayamvaram (One’s Own Choice), Adoor’s first film, released in 1972. Swayamvaram won for Adoor the National Award for Best Film, although the film, when it opened in theatres, was a flop. It was only when the film won the National award that the film was re-released and ran to packed houses.

Bhaskaran also tells us in this chapter that Adoor was very particular about the dialogues he writes. “I have very few dialogues in my movies, but whatever they are, they are very important...they cannot be changed this way or that way just because an actor wants it,” Adoor says. He rehearsed every shot, with all the camera movements, several times before he let the camera roll. Even with all this, Swayamvaram was completed in about 50 days of shooting. Adoor did not make films very frequently — while Swayamvaram was made in 1972, his second work, Kodiyettam came five years later, and Elippathayam was made four years after this. Satyajit Ray, Bhaskaran tells us, suggested that Adoor make at least one film a year — but he never did. Adoor says this is because he is lazy!

Another of Adoor’s films, Kodiyettam, shows the filmmaker’s use of natural sound throughout the film. Interestingly, the film had no background music.

However, he used natural sounds extensively, and for one sequence, even hid himself in a toddy shop and recorded the sounds there of men drinking and cursing one another!

But it must be noted that while on-location recording of sound has assumed great importance today, for a film made in India in 1975 this was a pioneering effort. (It was released only in 1977, because Adoor could not pay AVM Laboratory, where the film was processed — it lay there for a whole year, and when Adoor went to collect it, he found some rolls missing, and had to re-shoot some scenes!)

While we get many glimpses of Adoor Gopalakrishnan, the man, and the filmmaker, and the way he approached his work, I missed details of how the filmmaker worked with the rest of his crew members; his personal likes and dislikes and other details. There is just a fleeting mention of Mankada Ravi Varma, Adoor’s cinematographer for nine out of his 11 feature films, I also felt unhappy about the way this book abruptly goes into the section on each of Adoor’s films, and the fact that the book has no formal ending. It simply ends tamely after the chapter on Oru Pennum Raandanum, Adoor’s last film till date.

While the book was certainly an interesting read, albeit a little on the academic side, the finish seemed similar to lights coming on in a darkened cinema hall before a film ends.

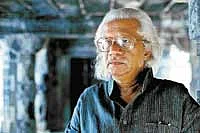

Adoor Gopalakrishnan

—A life in Cinema

Gautaman Bhaskaran

Penguin, 2010,

pp 218,

599