This decade witnessed remarkable advances in the rights of LGBTQ people with the overturning of Section 377 as well as the recognition of the rights of transgender persons. However, one group which had been left behind when it came to constitutional recognition were sex workers. The interim order of the Supreme Court in Budhadev Karmaskar vs Union Of India atones for this constitutional neglect by unambiguously recognising the right to dignity of sex workers. This recognition that sex workers have rights and that the right to dignity is not alien to persons in sex work has been widely welcomed by the sex worker movement.

With this order, the Supreme Court has taken an important step forward. While it has not recognised the right to sex work, it has unambiguously recognised that sex workers are persons under the Indian Constitution who cannot be deprived of constitutional rights, just because of their choice of profession.

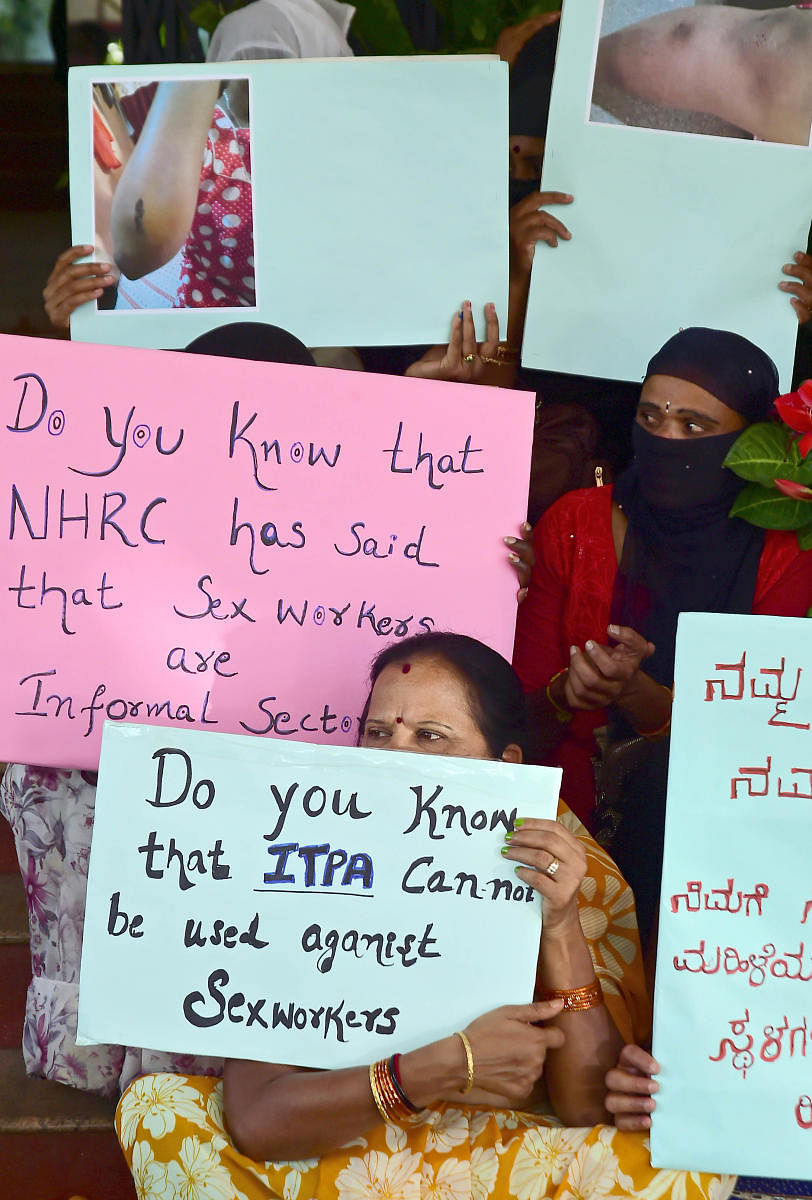

One of the persistent issues faced by sex workers around the country is police violence. This order for the first time recognises this brutal reality and observes that ‘police should treat all sex workers with dignity and should not abuse them, both verbally and physically, subject them to violence or coerce them into any sexual activity’.

One hopes that the Court follows through with more specific directives to address the scourge of police violence affecting sex workers.

Violence against sex workers has been invisibilised for too long and this order begins the long-overdue process of recognising that sex workers have the constitutional right to be free from intimidation, torture and sexual abuse.

Apart from police violence, the other key issue women in sex work face are arbitrary, coercive involuntary incarceration in rehabilitation homes. A study titled, ‘Raided’, conducted by sex workers organisation Sangram observes that women engaging in voluntary sex work are often picked up and detained in rehabilitation homes.

However, to get released from what is to all intents and purposes a prison takes a ‘large number of women from six months to a year’.

The order recognises this egregious violation of the rights of women to be free from arbitrary criminalisation by mandating that state governments should do a survey of all homes where women accused of Immoral Traffic (Prevention) Act (ITPA) offences are detained and then to ‘review’ and ‘process’ the release in a time-bound manner of all who are being detained against their will.

The above two directives are part of a series of sub-orders all of which are a welcome recognition that persons in sex work are entitled to constitutional rights and in particular to the right to dignity. The challenge is to ensure that the law in the books becomes the law in practice and begins to impact police and state behaviour which denies sex workers their human rights as a matter of practice.

(The author is a lawyer & writer based in Bengaluru. He is the co-editor of Law like love: Queer perspectives on law.)