The bird species which has most piqued the interest and imagination of artists, ornithologists and palaeontologists alike is the dodo which was endemic to the island of Mauritius. The ill-fated bird is often cited as one of the most well-known examples of human-induced extinction.

Bigger than a turkey in size and weighing about 20 kilograms, the flightless dodo was known to be an intelligent, naturally curious, and friendly bird. Large and plump in shape, it stood a little over three feet tall displaying a colourful beak, a bald head, curly feathers, long legs, and short wings. Hunted by sailors and invasive species, and with its habitat destroyed, the bird went extinct within less than a century of being discovered. The last recorded sighting of a dodo was in 1662; some reports suggest that the last dodo was killed in 1681.

“The dodo was a giant ground pigeon, unlike anything living today,” says English avian palaeontologist, artist and writer, Julian Pender Hume. “Despite its relatively recent extinction, the life history of the dodo continues to elude us. More is known about the dinosaurs, their population structure, nesting behaviour, eggs and young, than of a bird that disappeared relatively recently due to human interference… The dodo lived solely in Mauritius and we know it was extinct by around 1680, less than 100 years after humans inhabited its island home. But we don't know exactly how it got there in the first place, how it evolved, how big it grew or how it behaved.”

According to Dr Hume, the only near-complete dodo skeleton that exists is housed in the Durban Natural Science Museum.

A distinguished artist of the Mughal era, Ustad Mansur is credited to have made the most authentic and accurate image of a dodo possibly around 1627. Mansur’s study of the bird, rediscovered in the Hermitage Museum in St Petersburg in 1955, is hailed as the archetype on which all subsequent drawings of the dodo were made.

Historians assert that the dodo was brought through Surat to Emperor Jahangir's court via Portuguese-controlled Goa; and that the court artist Mansur made the painting by looking at the actual bird.

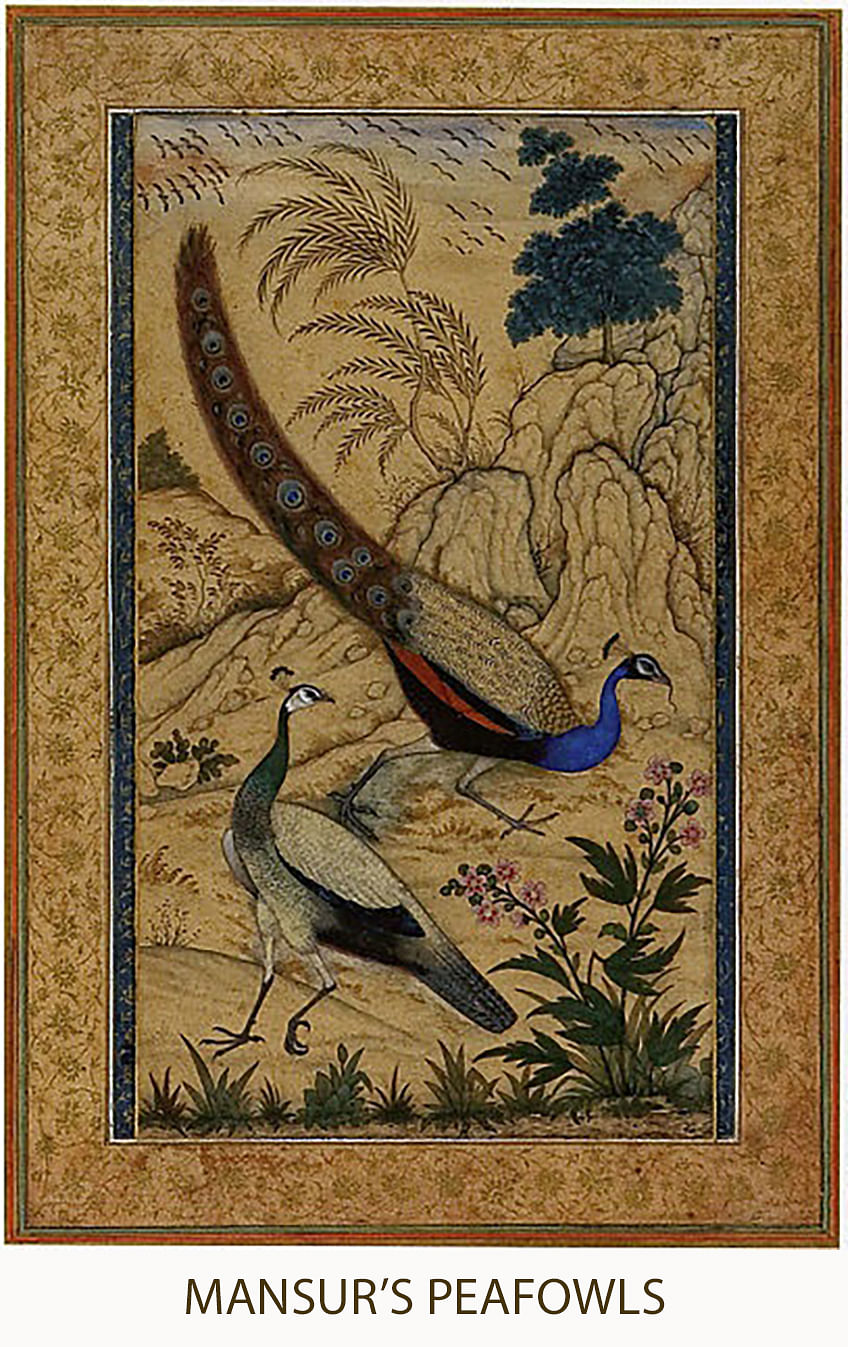

It is also recorded that Jahangir, like his father Akbar, was a lover of arts and took a passionate interest in the natural world. He (like his father) wrote extensively and commissioned court painters to paint detailed images to compliment his vivid prose. Among the various master artists of Jahangir's ateliers, Mansur was most notable for his exceptional skills in painting rare and unusual birds, animals, and flowers.

As Jahangir’s favourite artist, Mansur is also known to have accompanied the emperor on many of his travels and documented the flora and fauna of the area in his inimitable style. It is recorded that during a visit to Kashmir in 1620, Mansur had shown the emperor over a hundred flower studies including the one featuring the famous Red Tulip.

Shrouded in mystery

Very little is known about Mansur’s life beyond his exceptional paintings and their associated inscriptions. A junior manuscript artist and a gifted illuminator in the late Akbar period, there seems little doubt that Mansur shot into the limelight during the reign of Jahangir (1605 to 1627). Under the emperor’s patronage, Mansur produced exquisite works that eventually earned him the honorific Nãdir-al-’Asr (‘Wonder of the Epoch’).

Jahangir’s legendary interest in exotic animals and birds encouraged many visiting dignitaries to plan their gifts cleverly. As a result, the turkey cock, Barbary falcon, and zebra reportedly entered the emperor’s court as gifts. And so did the dodo. It was a common ritual that once an exotic animal or bird arrived, Jahangir would summon Mansur to paint it, while the emperor himself spent considerable time dictating a description of the specimen. Mansur would scrupulously study the specimen and meticulously extract the physical texture as well as the inherent character of birds and animals that were offered to him as specimens. Historians point out that he also had a deep empathy for his subject matter, the creatures and plants of India.

Not all of Mansur's birds, however, were based on reality. His immaculately rendered fantasy birds had their own beauty and charm. Mansur decorated his work with floral borders: a major contribution that became a distinct characteristic of Mughal art.

Ustad Mansur was not the only artist of eminence in the Mughal court. Abu al-Hasan (1589–1630) excelled in portraiture and was bestowed the title Nadir-uz-Saman ("Wonder of the Age"). Farrukh Beg (1545-1619), a Persian miniature painter, was one of the most exceptional manuscript artists of his time. Govardhan, who was an expert in painting holy men, musicians and eccentrics could distinctly capture the psychological state of his sitters. Other masters included Inayat, Manohar, Muhammad Nadir, Murad and Pidarath.

Historical fiction

Bangalore-based writer Vikramjit Ram’s recent novel ‘Mansur’ (Picador India) begins with the 48-year-old Mughal master about to paint the dodo’s eye. It is Saturday, the 27th of February 1627. The dodo’s eye, presently an empty white circle no bigger than a grain of millet, will take him an hour to finish. In two days, the ageing artist with failing eyesight must leave for Verinag. The road out of Agra to Kashmir is a month’s march.

Ram’s novel is a gripping piece of historical fiction with riveting plots and sub-plots, intriguing situations and characters tightly and seamlessly woven into a glowing canvas of ‘secrets, conflicts, half-truths, petty rivalries’. Ram has dedicated his book to eminent art historian Asok Kumar Das, author of the first book-length monograph titled Wonders of Nature: Ustad Mansur at the Mughal Court, (Marg publications, 2013).