As a leading light of photojournalism of her era, Margaret Bourke-White (1904-1971) undertook many critical and often mortally dangerous assignments across the world. As a freelancer and staff photographer of LIFE magazine, she covered a variety of historic events including the wars in Russia, North Africa, Italy, and Germany.

Among others, her trailblazing documentation of USSR’s industrial revolution in the 1930s; barbaric conditions in Nazi concentration camps after their inhabitants were liberated in 1945; and the emotionally and politically charged stories of segregation in the American South in the 1950s caught the attention of the world.

A keen eye

“What is amazing about Margaret Bourke-White’s life is the number of opportunities she managed to get for herself,” writes photographer Elsa Dorfman. “In photojournalism, getting where the action is, being there when it happens, is a major part of the talent and, ultimately, the achievement. And Bourke-White managed to get herself where things were happening when they were happening by working hard at being lucky and by her piercing intelligence and intuition… Like most photographers, she had the ability to focus her personality on the getting of the photograph — by being persuasive, charming, persistent, manipulative, whatever it took.”

A charismatic woman with beguiling looks, Bourke-White was known to work incredibly hard with legendary stamina and perseverance. Nicknamed “Maggie the Indestructible” by her colleagues in LIFE, she is said to have routinely consumed incredible amounts of film, and staying with heavy, outdated large-format cameras at a time when others were shifting to the slicker 35 mm.

Her biographer, Vicki Goldberg describes Bourke-White as “a true American heroine, larger than life — perhaps larger than LIFE”. Author and Professor Lynne Iglitzin says that through her photos, thousands were able to witness world events. “The fact that she was a woman doing these things, at a time when women were expected to focus on home and family, is perhaps the most impressive thing of all.”

Bourke-White died on August 27, 1971 at the Stamford Hospital, Connecticut after a long, heroic struggle against Parkinson’s disease. She was the first staff photographer of Fortune magazine in 1929; and LIFE magazine’s first female photographer in 1936. LIFE had published her last story in 1957, but kept her on the masthead until 1969.

Indian connection

Bourke-White, who came to India to record the run-up to the Partition in 1947, maintained a strong connection with the country. “The work in India had been a most stimulating part of my life,” she wrote in her autobiography, Portrait of Myself. “It was an inspiration to have such a vast subject spread on an enormous canvas and peopled with such extraordinary personalities.”

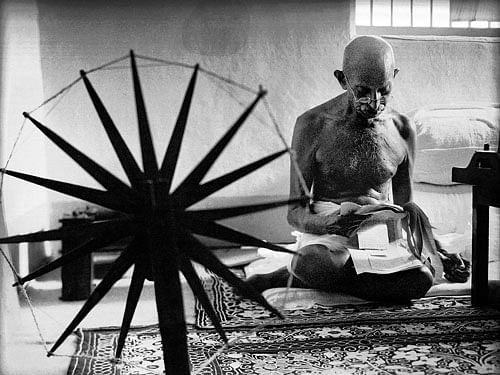

Her image of Mahatma Gandhi at the spinning wheel in 1946 became one of the best-known photographs in the world. She was also the last person to interview Gandhi just before his assassination on January 30, 1948.

Bourke-White described Gandhi as “one of the saintliest men who ever lived”, and felt that his death marked the end of an epoch. “It took me two years to appreciate the greatness of Gandhi. It was only in the last act of the drama, when he stood out so bravely against the religious fanaticism and prejudice that I began to glimpse his true greatness... Photography demands a high degree of participation, but never have I participated to such an extent as I did when photographing various episodes in the life of Gandhi.”

Bourke-White first met Gandhi in his ashram in Poona “where he was living in the midst of a colony of untouchables”. She saw him as “a spidery figure with long, wiry legs, a bald head and spectacles,” and wondered how could this little old man in a loincloth be leading his people to freedom and kindle the imagination of the world? “This was the first of many occasions on which I photographed the Mahatma. Gandhi, who loved a little joke, had his own nickname for me. Whenever I appeared on the scene with camera and flashbulbs, he would say, ‘There’s the Torturer again.’ But it was said with affection.”

Over time, the American photographer realised how important was the simple act of spinning the wheel was to Gandhi. “Understanding, for a photographer, is as important as the equipment he uses. I have always believed what goes on, unseen, in the back of the lens is just as important as what goes on in front of it. In the case of Gandhi, the spinning wheel was laden with meaning. For millions of Indians, it was the symbol of the fight for freedom… The charka was the key to victory. Non-violence was Gandhi’s creed, and the spinning wheel was the perfect weapon.”

Bourke-White’s last meeting with Gandhi had a poignant touch. When she folded her hands together in a gesture of farewell, she recalls him taking her hands and shaking them cordially in Western fashion. “We said goodbye, and I started off. Then something made me turn back. His manner had been so friendly. I stopped and looked over my shoulder, and said, ‘Goodbye, and good luck.’ Only a few hours later, on his way to evening prayers, this man who believed that even the atom bomb should be met with non-violence was struck down by revolver bullets.”

Bourke-White also describes the scenes following the assassination in great detail. “People covered the entire visible landscape until it seemed as if the broad meadows themselves were rippling away until they reached the sacred banks. I never before had photographed or even imagined such an ocean of human beings…The curtain was falling on the tragic last act. The drama I had come to India to record had run its course.

I had shared some of India’s greatest moments. Nothing in all my life has affected me more deeply, and the memory will never leave me. I had seen men die on the battlefield for what they believed in, but I had never seen anything like this: one Christ-like man giving his life to bring unity to his people.”