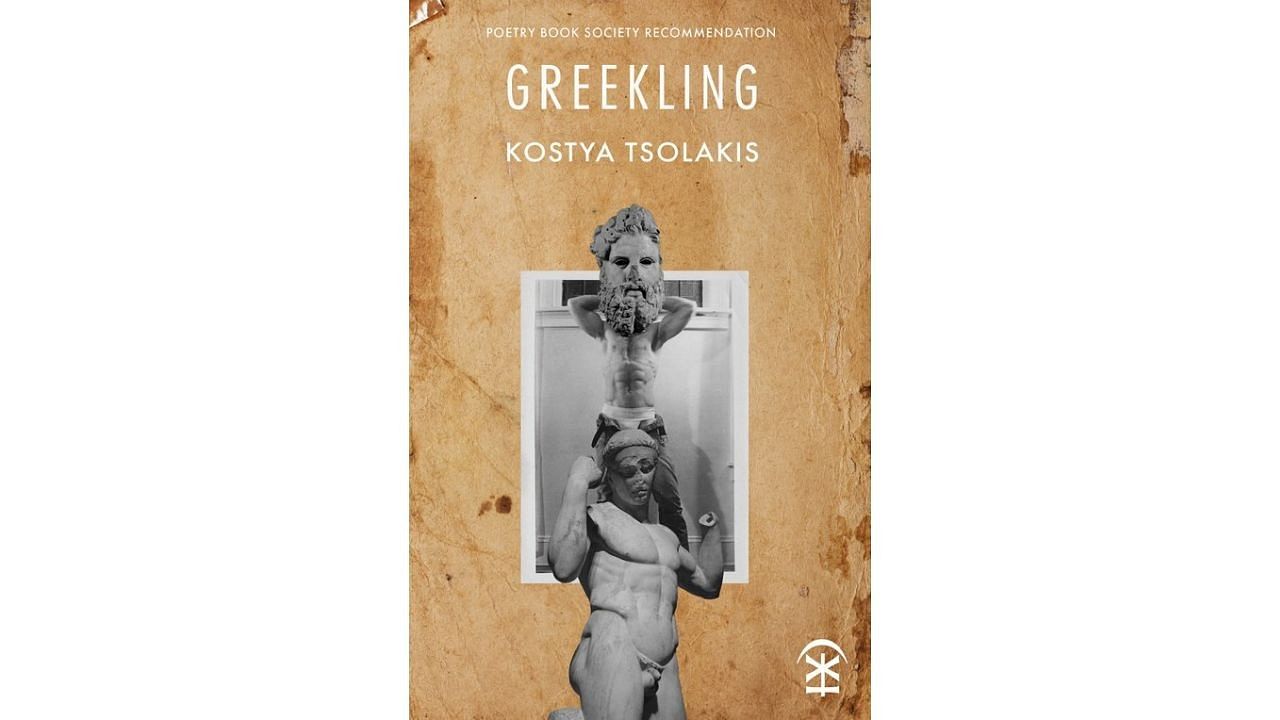

Kostya Tsolakis’ Greekling.

Credit: Special Arrangement

A fragment from the poem titled Naming It in London-based poet Kostya Tsolakis’ debut poetry collection Greekling (Nine Arches Press, 2023) effectively conveys the failure of the political class, which can be observed across geographies whenever faced with an epidemic, thusly: “Leaders say they are on it”. But what concerns them the most is their country’s perception abroad while “we run out of paper/ to list our dead”, submits Tsolakis.

Besides bearing witness to the AIDS epidemic, the poem also echoes the complete apathy of the privileged during the Covid-19 pandemic, placing it uniquely in the cult of universal and timeless poems.

Naming It is not an isolated example. Each poem in Tsolakis’ collection resonates with the present while recalling the past, attempts to exhume the stories of people who bore the cost of being themselves and presents Greek myth-histories, and champions queer ethnography in a way that makes it accessible for people of other cultures to find common expressions in it, transcending all sorts of borders. Tsolakis considers it a “big deal” to be on the shortlist of the 2024 Polari Prize for First Book, for it is “the kind of recognition I could only have dreamed of when I started writing poetry many years ago. It’s wonderful that Greekling is the only poetry collection (on the) shortlist. I grew up in a sleepy suburb of Athens, so to be recognised in this way, and for something I wrote in my second language, will always encourage me to keep going.” In an exclusive interview, the poet shares insightful details about Greekling, unpacking this layered collection for its readers. Edited excerpts:

The title Greekling is very intriguing. How did you arrive at it? And what cultural and political importance did it signal, convincing you to choose it as the title of your debut collection?

An ex used to affectionately call me ‘Greekling’, so it’s a word I’ve had in my mind long before I’d even written the collection’s first poem. I then came across the word’s entry in an English dictionary and was struck by how disparaging its use has been through the centuries, starting with the Romans, who coined it to describe fey intellectuals who admired all things Greek. Meanwhile, in Modern Greek, the term is used to describe someone as subservient, undignified, or a turncoat, essentially. As someone who grew up in Greece but felt marginalised by his culture, especially as a gay teenager obsessed with British literature and music, I felt this word described perfectly how other, more traditional Greeks could see me. Four years or so before the collection came out, I’d settled on Greekling as its title, and it was rather cool to also reclaim the word and turn it into an endearment for myself and others marginalised by their surroundings.

Greekling has several poems reminding readers of the lives lost to bullying and discrimination (The Case of Vangelis Yakoumakis), particularly the murder of the HIV-AIDS activist and drag performer Zak Kostopoulos (Someone Else’s Child). Did you want to use the poetry form to re-socialise these incidents, cementing the fact that the fight for queer rights across the world is essentially the same?

I spent many years feeling that my voice did not matter. I feel strongly about injustice, about being cornered, starved, or being made to feel you can’t breathe because of unreasonable expectations placed on your shoulders by your own family, tradition, gender roles, and history.

The poetry I admire stops me (in) my tracks, and the form of poetry has offered me a way to voice my thoughts and responses to events in a way that also satisfies my indelible urge to create and the love I have for rhythm and brevity. Certainly, I do hope that my poems add to the common fight for queer people across the world by highlighting, in a global language like English, the experiences of the LGBTQIA+ community in Greece.

You’ve also leveraged several queer historical events from Greek history and juxtaposed them with the newer culture of queer belonging (dating apps, etc.). Could you share some parallels and differences between the two you observed while penning down these poems?

My writing is deeply driven by wanting to understand, celebrate, and memorialise desire. This evergreen feeling — at times painful, maddening, but also monumental — is what I enjoy reading about most in fiction and poetry. I relate to the vulnerability that desire makes Catullus feel when he addresses Lesbia, and Pip in Charles Dickens’ Great Expectations. It thrills me that words describing desire, written thousands of years ago, can move me so profoundly.

I aim to evoke a similar emotional response in my readers. By positioning my poems in different eras, I can draw parallels between ancient and modern queer desire.

While the methods of finding and expressing desire have changed dramatically over the centuries, the underlying emotions and experiences remain, in my opinion, the same. This exploration of both the similarities and differences between ancient and modern queer desire is what excites me most about my writing. It’s something I plan to continue doing in my next collection, although this time I’ll be drawing from other eras I’m interested in, such as the Byzantine period and World War II.