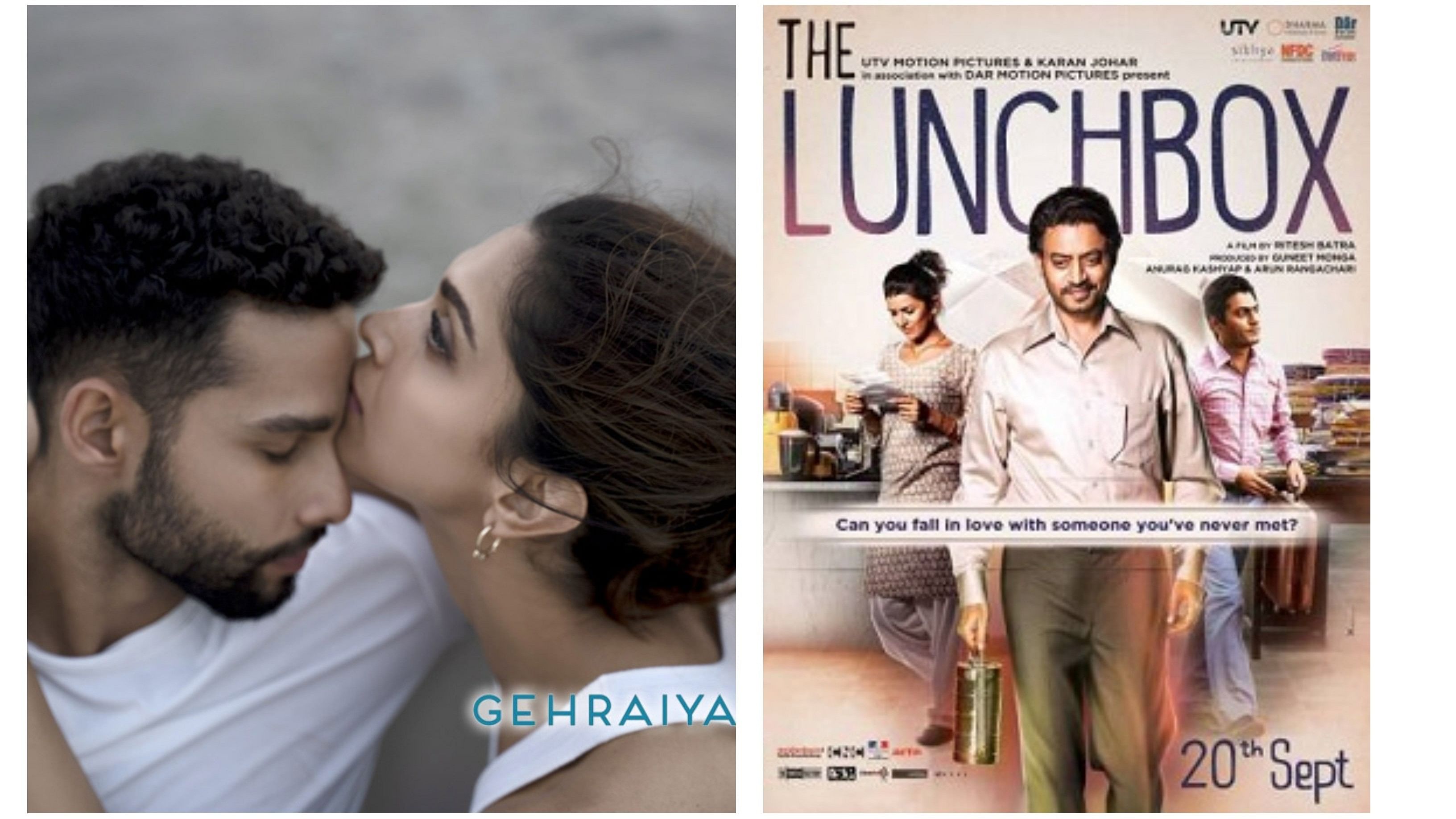

Images for representation.

Credit: special arrangement

One of the human behavioural complexities — infidelity, has been the focus of films and TV for a long time. Many moviemakers have delved into this subject giving the viewer insights into the acts of infidelity — the reasons, the complications, and the consequences. But why is it that a situation that is 'morally' acknowledged to be harmful to society, and an emotional disaster that rarely ends happily, the predilection of movie directors? Is it because we have realised that it is not uncommon in reality? Or is it because it catches the fancy of the viewers who are trying to justify their acts? Or do some want to experience a passing fancy virtually?

There was a time when in cinema, women were depicted as either the vamp or as being righteous. Vamps were the seductress, marked by promiscuity and desires. But their destiny was to end up alone. The leading lady was a reminder of ‘an ideal woman’. She was there to shed a bucket load of tears and endure every hardship. But the coveted prize — the hero, was hers in the end. Amidst all the drama that used to unfold in 120-180 minutes of the movie, the hero was the only person who used to come out unscathed with zero consequences for his actions. Infidelity was never his mistake, but the vamp’s, who lured him with her tactics.

Sometimes he was the pitiable man with a monotonous life with a wife who was managing the household and not tantalising him. According to those movies, the hero’s infidelity was justified and forgiveable. In Biwi No 1, the whole drama unfolds and the wife blames the other woman for her plight. In the end, the hero returns home to his loving wife’s arms.

These movies treated infidelity as a device for the redemption of the hero’s character. Similar was the case of the film Masti, where three friends out of sheer boredom, and frustration try to cheat on their wives. The cheating leads to sexual-comic sequences, giving makers enough room for one-liners. Women were on the fringes and infidelity was used as a medium to deliver slapstick comedy.

Although characters often meet the consequences for their actions, the charm of illicit love stories never diminishes. Maybe it is getting lost in a fantasy that one would not fulfil in real life, or just the general excitement that comes from a movie’s passionate, prohibited love.

With an array of emotions involved, it challenges the creativity and skill of the scriptwriter and director. The discretions bring out the full circle of emotions — love, hate, anger, trust, perseverance, vengeance, forgiveness, and redemption. There has been a shift towards more nuanced and complex portrayals of women and infidelity, as the stories questioned the societal norms.

The portrayal of flawed characters making choices based on their needs reconnoitring alternate paths of understanding love and intimacy. Aruna Raje’s Rihaee used infidelity to highlight the hardships, loneliness, and sexual frustration of women whose husbands migrate to cities for a living. Husbands find a way to tackle their urges in the company of prostitutes. And yet they expected wives to remain loyal.

Similar lines were explored in Prakash Jha’s Mrityudand. The ignorance fuels the wife’s infidelity, the insensitivity of the husband, and the loveless marriage. The illicit relationship leads to pregnancy. When asked whose child it is, she smiles and says, “mine”. The why and how of physical infidelity were used to deliver a strong message.

The path-paver which showcased an unapologetic woman was Ek Baar Phir. Despite being a simple middle-class girl, Kalpana refuses to adjust to her superstar husband, Mahendar’s philandering ways. She eventually finds love and breaks free of the suffocating union. And yet, it was bold of the makers not to give closure to her new relationship through a visual depiction of commitment. Infidelity was justified for being the result of her unhappy marriage. Their intricate storytelling sometimes doesn’t let us hate the infidel, but rather be sympathetic towards them.

The indifference in a marriage often leads to seeking solace in warm human companionship, escaping the mundane and pain. Be it Choti Bahu in Abrar Alvi’s Sahib Biwi Aur Ghulam or Ila of The Lunchbox.

How beautiful was the exchange of letters between Ila and Saajan in Ritesh Batra’s The Lunchbox! Two people, who never met, develop a bond so intimate that it becomes a thread to redeem themselves. Similarly, the unconventional friendship of Bhootnath and Choti Bahu leads to nothingness, but who would blame any of them? For Ila, the human connection transpires into love and strength to escape her plight.

These movies delicately portrayed one’s yearning for human connection and a desire for companionship. And can we forget Rosie and Raju’s love, betrayal, and regrets in the cult classic Guide? It exhibited how an act of infidelity saves someone from a loveless marriage. But it was just the tip of the iceberg. The movie explores different themes of betrayal, loss, regret, and redemption.

The film’s most evident aspect is the imperfect characterisation. There is no heroic quality in any of the people from Guide’s world. Like us, they are flawed, and imperfect, struggling with the highs and lows of life. They are anything but typical self-sacrificing figures. The motivations, desires, and vulnerabilities of characters lead to deceit and suffering. The biwi and sahib of Saheb, Biwi Aur Gangster and Vishal Bharadwaj’s Maqbool are films that not only explore the infidelity of their female lead but also her clever schemes to get rid of unwanted elements. The gangster does everything for Biwi’s love whereas Maqbool is torn between Nimi’s love and loyalty towards Abba ji till his last breath.

Bollywood’s approach to the complexities of infidelity from a woman’s perspective is multifaceted and reflects a shift in societal values and individual perspectives. These films often aim to spark conversations about love, loyalty, needs, and the intricacies of human relationships. While it is generally assumed that movies on infidelity have either slapstick comedy or erotica, when we look back at the films that were, there seems a lot more to infidelity as a subject. Leading ladies have gazed the lens of infidelity to tell stories that are compelling, and daring and make us question the preset standards.

Esther Perel said it well, “As tempting as it is to reduce affairs to sex and lies, I prefer to use infidelity as a portal into the complex landscape of relationships and the boundaries we draw to bind them.”