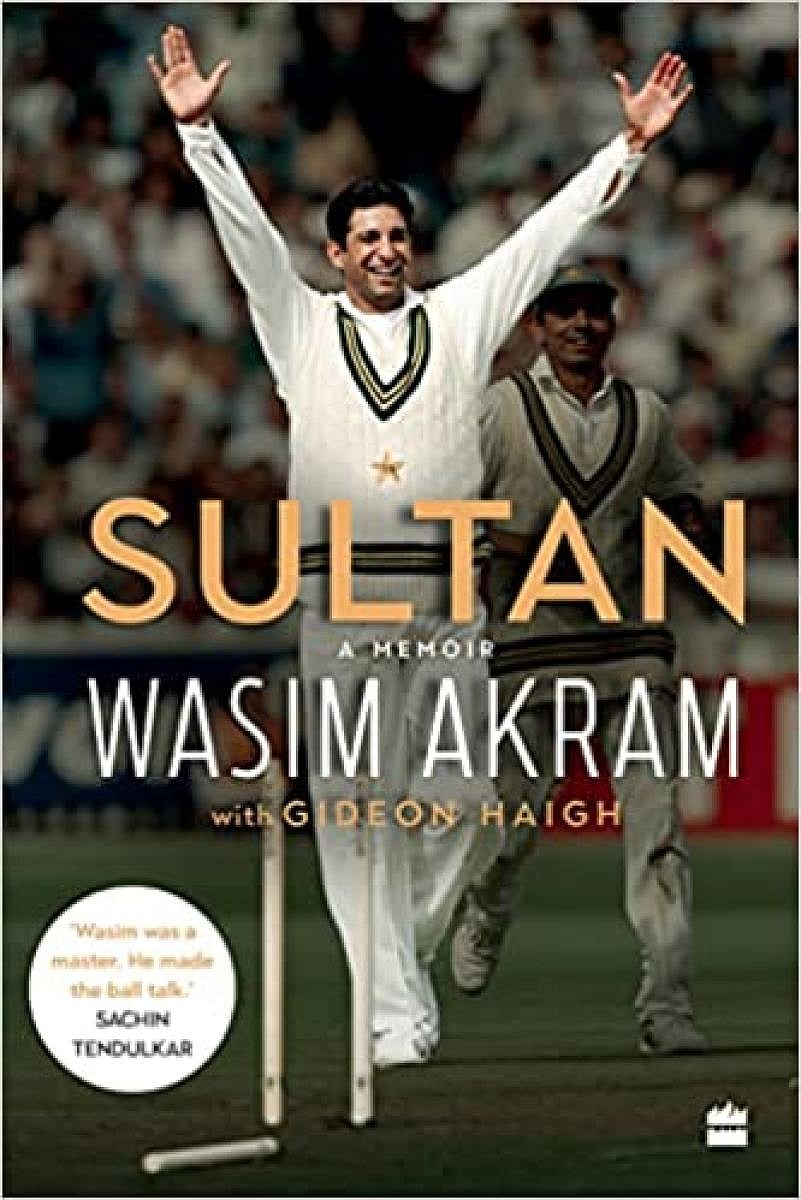

The title is logical, inevitable even. Wasim Akram was nothing if not the Sultan of Swing, so it’s befitting that his memoir is called Sultan. Co-written with senior writer Gideon Haigh, Sultan offers plenty, as is to be expected. It takes one through Akram’s evolution as a paceman extraordinaire from the dusty bylanes of Model Town in Lahore to the most exotic and revered cricketing locales in the world, charting a journey of exceptional highs and numbing depths, both professionally and personally.

Akram was a force of nature, inarguably the greatest left-arm fast bowler in the history of the game. With the old ball and new, from over the wicket and round, from a longish run-up or an ultra-shortened one to right-hander and left-hander alike, he posed a plethora of threats. No one was ‘in’ against Akram, not at the start of one’s innings or even when well past a century, because a slice of magic wasn’t too far away when the big fella bustled in, primed to unleash a toe-crushing yorker or a head-threatening bumper.

Mentor worship

Sultan provides a ringside view of how Akram came to be the maestro he was, under the wise tutelage of his mentor and role model, Imran Khan. Sultan makes it clear that to Akram, there was Imran, and then there were the rest of his colleagues, including Javed Miandad who first spotted him and fast-tracked his initiation into international cricket and Waqar Younis, whom Akram himself first identified as one for the future and alerted Imran to the possibilities that lay ahead. Akram has reserved unalloyed praise and unabashed reverence for Imran; the others feel the sting of his wrath. Be it Saleem Malik or Aamer Sohail, Rashid Latif or Majid Khan — intriguingly, his hero Imran’s cousin — Akram has unsparingly taken them down, holding them responsible for the toxic culture that pervaded Pakistan cricket in the immediacy of Imran’s retirement after leading the team to the 1992 World Cup victory.

Perhaps, because he was so open and voluble in his worship of Imran, Akram was left friendless after his mentor called it quits. At various stages, it emerges that Akram had lost the joy of being part of a winning if volatile team. His one-time comrade-in-arms in knocking oppositions over, Waqar, and he weren’t even on talking terms for a long time even as they continued to hunt in pairs, and for extended periods, Akram went through the motions lonely and left to his own devices, offering little by way of inputs once his colleagues rebelled against him and ensured that he was stripped of the captaincy the first time around.

Just how little affection he has for his compatriots is evidenced by the fact that of the 15 endorsements from celebrated international stars — one at the start of each of the chapters — only one is from a Pakistani. No prizes for guessing that that one person is Imran.

While Sachin Tendulkar, Rahul Dravid, Anil Kumble and his great pal Ravi Shastri, among others, have all spoken glowingly of Akram the competitor and Akram the person — he pretty much embodied the ‘smiling assassin’, barely using a sledge, always charming and affable — the Pakistani great has pointedly passed up the opportunity to elicit the opinions of his countrymen, revealing just in how much ‘esteem’ he holds them. The book begins promisingly with revelations of the tips Imran bestowed on his young charge, but as it unfolds, it doesn’t live up to the initial promise.

The narrative is a whirlwind, only pausing a little here and a little there for breath. Akram writes about his travails with the police in the Caribbean when he and a couple of his teammates were detained on tenuous charges of drug possession, and vehemently protests his innocence when it comes to issues of ball-tampering as well as match-fixing.

He throws light on his addiction to cocaine in the period leading up to the unfortunate demise of his first wife, Huma. Huma and Shaniera, to whom he is married now, come through as strong-willed, independent women who have played crucial roles in ensuring that Akram remains a grounded, friendly soul, untouched by the greatness that he wears lightly.

Haigh is an interesting choice as co-writer, not least because he is not from Akram’s part of the world and therefore might not have watched/known him as intimately as some others.

His voice comes through in the book more than Akram’s; after all, one of the great challenges of helping someone write his story is to slip into the character of the protagonist.

The nitpickers might point to a certain carelessness in the manner in which obvious facts haven’t been cross-checked, and they might have a point. But viewed against the larger canvas, that’s but a minor annoyance. Sultan is engrossing and enlightening, though it needn’t have stopped at that.