It’s a curious word… hanji. The Hindi hanji is of course ubiquitous across the country, and globally too. Now, its Korean namesake is connecting artists from different countries, especially since the last decade. Such is the charm of Korea’s ancient textured paper, hanji, handmade from mulberry bark, with an origin dating back to the third century. Hanji originated in China, found acceptance and evolved an identity of its own sometime between the 3rd and 6th centuries in Korea, and was even traded with China in the course of time.

Set it right

So, what differentiates hanji from other traditional paper? Material strength, resilience and longevity are some aspects. A Korean proverb goes on to say that ‘paper lasts a thousand years’, no doubt inspired by the fact that hanji can last well beyond a thousand years. Observe that the Korean manuscript Great Dharani Sutra of Immaculate and Pure Light (704 AD) or Mujujeonggwang Daedaranigyeong on hanji is regarded by many to be the first printed document in the world!

However, what holds the charm for contemporary artists is hanji’s unique texture, which comes from elaborate processing. Processing traditional hanji is perhaps an art by itself, and requires an expert’s judgment and handling.

To begin with, the mulberry bark dak is sun-dried to make dried dak heukpi, which is soaked in water for 24 hours to enable removing the outer layer of the bark. The rest of the bark baekpi is then boiled in water containing buckwheat husk for a few hours and then pounded on a stone surface, after removing the husk, of course. After pounding, it is mixed with the sap of the local plant aibika and then dried as sheets on bamboo supports… and thus emerges hanji, ready to humour an artist’s muse.

The texture and hue of the hanji depends on the multitude of steps in the process, and hanji made by one artisan can be quite distinct from the hanji made by another. So it is that though the hanji-making process has been extensively documented, most artists working with hanji visit Korea to learn first-hand the hanji-making process from a master hanji-maker, because it is his unique way of processing that makes the paper what it is.

Today, hanji art is making not just a comeback in Korea, but finding new followers across oceans. A case in point is Hanji Translated, a transnational coming together of 13 contemporary artists from India, South Korea and the United States who work with hanji — Nirmal Raja, MarnaBrauner, Shormii Chowdhury, Sudipta Das, Christiane Grauert, Ravikumar Kashi, Kwon InKyung, Aimee Lee, Jessica M Ganger, Song Soo Ryun, Lim Soo Sik, Julie VonDerVellen, and Rina Yoon — artists known for their evocative handling of material. Consequently, today, hanji is playing host to not just new streams of thought, but new possibilities of its own existence; not surprisingly then, these artists are ever-eager to learn from each other. Thus it came to be that earlier this year, Chennai, courtesy InKo Centre, saw the coming together of these artists.

The way a hanji paper is made allows for it to stake claim as a work of art, and not just in it serving as a conduit for expressing an idea. This is the same reason why an artist’s work sees a unique transformation with hanji. So these were referral points in Hanji Translated, as much as the themes they espouse. So ultimately, while Hanji Translated explored concepts relating to transcultural communication and issues relating to history, identity, migration and memory, what stayed more in the mind was the material of hanji itself.

Hanji Translated saw traditional dolls made from hanji, corded and twined hanji fashioned into various forms, laser-cut hanji pieces, assembled screen printed hanji, inkjet prints, intaglio prints, digital print on hanji (Korean paper) — pieced, folded, machine stitched, tempera on silk and paper pulp, ink and photocopy transfer on hanji paper, and embroidery — an expanse that stretches from rediscovery of an ancient material to a re-inventive exploration of its material nature.

Re-looking hanji

As Christiane Grauert mentions, her Gossamer States series follows in the tradition of jeonji, Korean paper-carving, but shifts from the traditional hand-carved approach to using technology (laser-cutting) to push the boundaries of the material. Likewise, Nirmal Raja, an artist based in Milwaukee, Wisconsin, USA, and someone who curated Hanji Translated, has used both screen-printed and hand-cut maps and hanji paper in her installation Blurred Boundaries.

In one of his works, Ravi Kumar Kashi has expanded the fibrous bark manually by delicately pulling and spreading it, a technique he learnt from his teacher Seong Woo.

Aimee Lee, a Korean-American artist, papermaker, writer, and a leading hanji researcher and practitioner in North America elaborates, “For the last decade, I have made art from paper that I make directly from plants, in the lineage of hanji. Hanji was used for household goods, worship, agriculture, and even war. My job as an artist and researcher is to follow this long historical thread in both directions, by unearthing past roles of hanji and creating new ones for today. Specifically, I make objects for the space that I inhabit as an American born to Korean parents.” She goes on to say that her most powerful expressive tool is hanji itself.

Equally illustrative is artist Marna Brauner’s point that the history of hanji in Korea is as a material for building, rather than a substrate for picture-making. “During my first trip to South Korea in 2012, I was amazed by the indigenous objects, both historical and contemporary, that were made by the cutting, layering, twisting, gluing and sewing of this paper to produce sewing boxes, lacquered containers, furniture and even funereal garments. It is this allusion to function that I hope is conveyed in my work”.

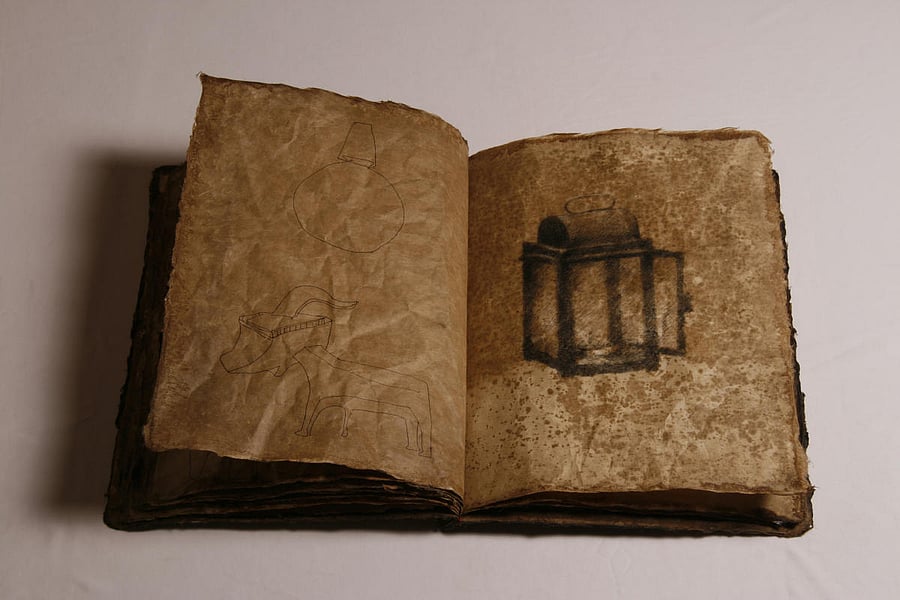

It’s also intriguing to see hanji platforming philosophical inquiries that trace its origin to other civilisations. For instance, Ravi Kumar Kashi’s artistic exploration of the concept of karma comes alive visually with Book of Destiny, an ink and photocopy transfer on Japanese raka-stained hanji paper that displays a grid on the leaves of a weathered, open book.

It is curious that this ancient paper that was once the prerogative of statecraft and scripture, and later on as the material of objects of ritual and everyday usage, is now being explored as objects of expression and for themes of more pedantic concepts. What makes this possible is the versatility of hanji and the enthusiasm of contemporary hanji aficionados to go back to hanji’s roots and revive it as material and muse.