Jews all over the world recently celebrated Rosh Hashanah, the Jewish New Year, as the Shofar or Ram’s horn was blown with a resounding ancient sound. In India, we greeted each other and had apple slices dipped in honey for a sweet beginning. The Bene Israel Jews of Western India, Cochin Jews, Baghdadi Jews of Kolkata, Bene Ephraim Jews of Andhra Pradesh and Bnei Menashe Jews of North-East India also made sweets or cakes with ingredients like coconut, wheat extract, semolina or rice flour in accordance with the ‘Jewish Dietary Law’ of not mixing meat dishes with dairy products. Platters of offerings were prepared for the New Year, like the Bene Israel Jews arrange a platter with a whole fried fish, cooked meat, a bhakhri or flat-bread, bowls of apple slices, honey, pomegranate seeds, boiled cubed potatoes, doodhi or bottle gourd, beetroot, green chauli or black-eyed beans along with goblets of sherbet. While Bnei Menashe Jews prepare a platter of fish heads, challah bread, cooked pumpkin pieces, boiled beans, fried onion roots, carrot slices, fish or meat curry with, pomegranate seeds, almonds, sliced apples, honey and goblets of sherbet. Each community prepares these platters according to available ingredients.

The Bene Israel Jews also prepare a Malida platter for a thanksgiving ceremony for Prophet Elijah; with sweetened poha mixed with grated coconut, garnished with raisins, nuts along with dates, bananas, chopped fruit and rose petals.

I have fond memories of the time when I lived in a joint family in a big haveli-like house in a Pol of the old city of Ahmedabad in Gujarat, where Shabbath prayers were held on our dining table and traditional Jewish food was cooked for dinner or on Sundays for lunch or for festivals. Yet, I had a craving for Gujarati food, as fragrances of Farsan or savoury snacks wafted into our house. Much later, whenever I invited vegetarian friends for lunch or dinner, I realised that my food was never as good as theirs. So, as a challenge, I started making a vegetarian green masala curry which is normally made by Jews with chicken, mutton or fish. I served it with my favourite Tilkut potatoes, coconut rice and a dessert of sweet puris or kippur-chi-puri, made by Bene Israel Jews to break the fast of Yom Kippur or Day of Atonement. They loved it.

Jewish cuisine has some regional influences, but it is made with a difference, as we observe a strict Jewish Dietary Law, which says, ‘Thou shall not cook the lamb in its mother’s milk.’ So, different sets of utensils are used to cook meat and dairy products.

All over India, Jews make grape-juice sherbet for Shabbath prayers or other festivals. Non-vegetarian dishes are made with coconut milk; similarly, rice puddings are also made with coconut milk; instead of milk, like chak-hao made with black rice by Bnei Menashe Jews of Mizoram. We also prefer fish with rice and a variety of curries made with red or green masala.

Unlike western countries, some ingredients are not available off-the-rack to make Jewish recipes, so local ingredients are used, like for Passover, we make date sheera and matzo a flatbread, which is made with unleavened wheat flour and roasted on a tava. Similarly, we use sprouted flat beans or field beans to break the fast of Tisha B’Av. And, Bene Ephraim Jews make a delicious chicken curry with gongura leaves, poppy seeds, grated coconut, cashew paste, which is mixed with the basic masala and served with colourful festive rice.

There are about 5,000 Jews in India. We are a mini-microscopic community and with each emigration to Israel and other western countries; we are decreasing in numbers, so some traditional foods are forgotten. Yet, while travelling, I discovered there was always someone; who remembered a recipe and gave it to me. It is important to add here that although many Indian Jews speak English, along with regional languages; our prayers are chanted in Hebrew.

Interestingly, many Indian Jews are vegetarians as Kosher meat is not always available and almost always, most meals end with fruit. Most Indian Jews have in fact preserved the ‘Dietary Law,’ which is the base of all Jewish cooking, which can be seen in the homes of the five Jewish communities of India.

Indian Jewish food has some regional influences and ingredients, as each festival or event is celebrated with a specific ritualistic, traditional recipe. Yet, each community makes some recipes, which are similar to the country of their origin, which they fled due to persecution; and came to settle in India, like sesame chutney, fish egg curry, kooba dumplings, mahmoosa, pastillas, chik-cha-halva, semolina or coconut cake, soya bean sauce and bamboo shoots with green chillies. Here, I discovered distant flavours of Israel, Persia, Spain, Middle East and the Far East, as the Jewish tradition of food is not mere memory, but a heritage passed on from one generation to the next which needs to be preserved.

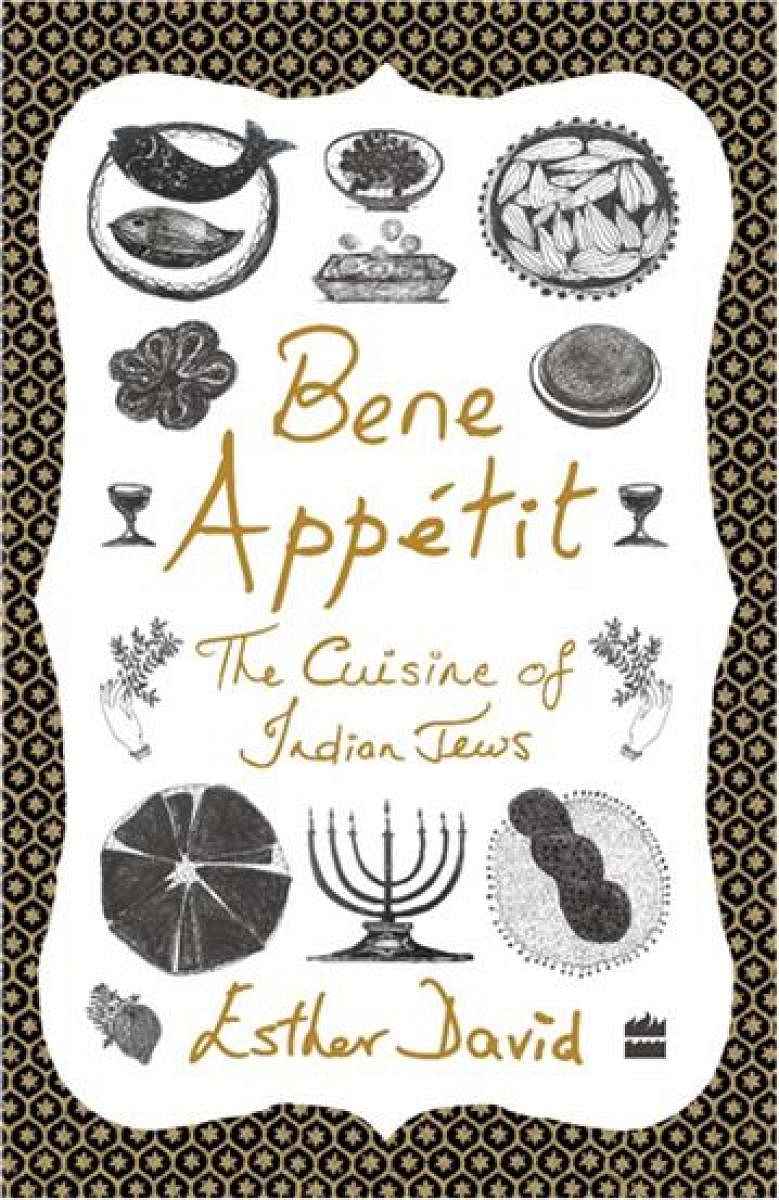

(The writer is the author of Bene Appétit The Cuisine of Indian Jews published by HarperCollins India.)