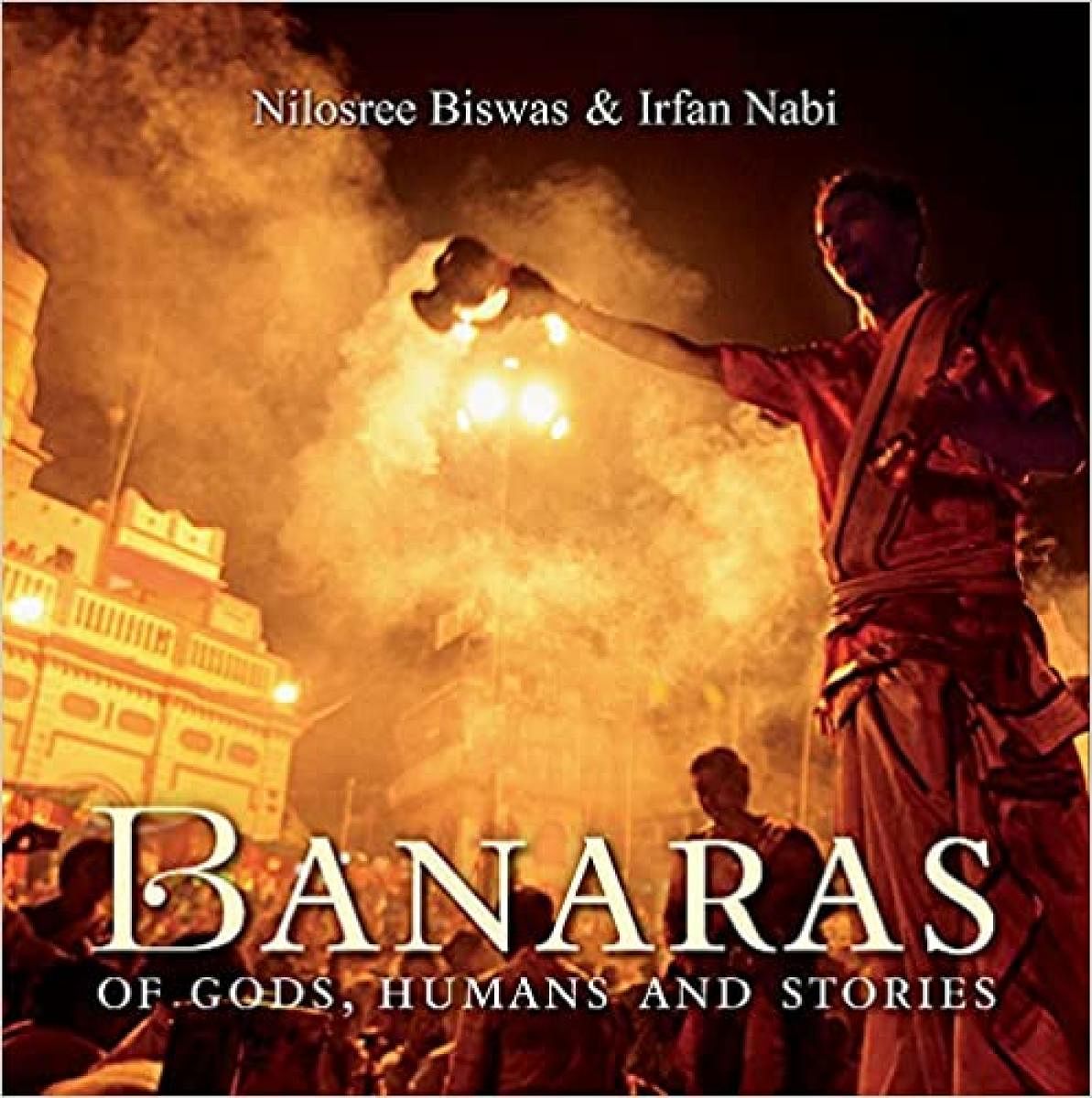

How many cities have their skylines represented in a saree design? Probably just one, Banaras. Recognisable as a stretch of ghats foregrounding an uneven row of fortifications, temple spires, domes and minarets, the iconic skyline has a mystique that is reflected in the city’s many names — Kashi, Avimukta, Rudravasa, Anandavana, Varanasi. As the epicentre of spiritual India, Banaras is where devout Hindus hope to die, but its richness actually lies in the spaces that the living occupy. These are explored in Nilosree Biswas and Irfan Nabi’s book, Banaras: Of Gods, Humans And Stories.

Despite its coffee-table book format, to call it another arty volume on a photogenic city would be unfair. While it packs in the aesthetics of one, in its themes and writing style — perceptive and introspective — it is akin to a travelogue. Sample this passage that invites the reader to view the ‘long rows of stone steps on the riverfront, that lead upwards into alleys narrow and winding, never in 90 degrees to each other, laced with temples new and old, crumbling houses, shops, half-broken balconies, more temples, cows, cow dung, cheap and fine saree shops, looms weaving unreal fabrics, tea stalls, dargahs, and schools rickety and old with peeled off signboards. And there are people, hundreds, thousands, and more, and the invisible divine who is supposedly governing this space, the omnipresent.’

Cultural syncretism

Using prime texts like the Puranas and travel accounts from pre-colonial and colonial eras, Biswas examines the city’s ‘2,500 years of continuous habitation’. Its topography is explained via the charting out of timeless pilgrim circuits, the Panchakroshi and Antargriha Yatras, and descriptions of famous ghats along the Ganga who, as a provider of salvation and hence important in funerary rites, is also ‘pranadayini — the giver of life’. Though eternal in concept, Banaras also has a history — narrated by its architecture. The Mughal period was significant when mansabdars to Akbar, such as Man Singh, built palaces and temples ‘representing the inclusiveness of the emperor’s policy and Mughal urbanism.’

The contribution is noted of other Hindu royal families in constructing ‘signature architectural markers on the banks of the Ganga ‘resulting into virtually a reinvention of the riverfront.’ Among them is a queen too, Ahalya Bai Holkar, who restored and redesigned Dasashwamedha Ghat.

The author offers a ‘people’s narrative’ to view the city’s pluralistic lifestyle and cultural syncretism. In a chapter titled ‘The Material Connect — Made In Earth’ we get glimpses of a different Banaras ‘that is high in cultural ecology and believes in the lived life.’ This is the world of the karigars, artisans such as the brocade weavers, makers of musical instruments, metal workers, wooden toy makers who ‘live in defined mohallas or localities marked by the most simple of undefined landmarks of a well or a tank, a temple, or a ubiquitous shop, or even a tree…The sense of peripheral is malleable for Banaras and, thus, a pipal tree can act as validating mapping indicator of a mohalla.’ Indeed, reading the book itself feels like a walkabout down the lanes of a mohalla.

Walking about is, in fact, a bonafide activity for the locals. They do it as much as the visiting pilgrims. Unlike the latter, however, the locals are out without a purpose. So much is this loitering a part of Banarasipan, (which the author calls ‘a way of life through the last few centuries’), that they even have a name for it: Bahari Alang. Call it leisure, mauj or masti — it’s something they love in whichever form it takes, from wrestling to playing chess to savouring the famous Banarasi paan.

At its core, the author explains, lies the mythology of Shiva, the real lord of the city, ‘a free-spirited, content, carefree wanderer…an itinerant at heart, always rebelling against the norms.’ While he is a frugal eater, his wife Annapurna, ‘the keeper of a magical kitchen’, is equally revered, and in this department, ‘the offerings that Banaras has are infinite.’ Sacred, profane, but never mundane, Banaras invariably presents a challenge for writers. Well-researched and sensitively written, this book does a good job of meeting it.